Living Matter

I never made a decision to become a film editor – or, in any case, I didn’t decide upon it at a young age and follow a single career path. It’s important to say this because too often young people are asked to have a well-defined and realistic life plan, prove their efficiency, and know how to sell themselves. Yet it’s only by being open to surprise and movement, by following passions seemingly disconnected from what’s referred to as reality, that you build your life, or rather discover it. Every day I’m a little more aware of the extent to which all the paths tried out and passions followed, the encounters I believed in, nourish who I am today, what I do, and how I do it.

When I was young I had a passion for Chinese civilization and thought. I was disturbed and fascinated by the notion of emptiness as an active element, by the importance of letting-happen, and by the idea that strength comes from patience and flexibility. And I was also attracted to how, in Chinese languages, saying or writing a word is like telling a story.

In Chinese script, combining different images creates meaning. For example, the moon and sun together signify luminosity, and a pig under a roof means a house or home. This script is far more than a transcription of spoken language. Each mark has a codified meaning, but beneath this first layer there are other deeper meanings “always ready to emerge,” as poet and translator François Cheng puts it. I immediately liked this constant tension between an apparent linearity and the temptation to escape it, as if it were echoing my own ambiguous relationship to logic, which both attracts and worries me. Cheng also says that Chinese is not conceived as a system that describes the world but rather as a representation that organizes and triggers meaning by bringing to light the hidden links between things, between man and the living world.

In Taoism one finds the idea that you shouldn’t forcibly try to explain everything, but instead let things come naturally. You create a movement, and Taoists consider that life is nothing other than this movement. As philosopher François Jullien puts it: “You have to get away from a spectacular conception of the effect to understand that an effect is all the greater when it is not aimed for, but is an indirect result of a process, and that it is discreet.” This suggests that process and effect are connected, and that meaning arises from the back-and-forth. This notion of movement is connected to another important issue in Taoism: emptiness. Taoist emptiness is the opposite of a no man’s land; it’s where transformations take place and connections are forged, where things refuse to be set in stone, and where life force gathers, making it possible for meaning to arise.

Emptiness is also central to Chinese pictorial art, as it upsets linear perspective and enables a different kind of connection between painting and viewer. I remember being struck by a story about the painters of Chinese antiquity, how they considered nature so beautiful and complex that it was useless to try and faithfully reproduce it. They decided to paint exclusively with black ink in order to allow viewers to imagine the colors. It is this space left to our imagination that sets us in motion, sparks thought, and creates our individualized relationship to the work.

I follow these principles in editing. I’m not looking for a film to describe reality, as is often expected of documentaries, or even for it to tell a story, as is often expected of fiction films. I’m trying to create a space in which all viewers can create their own connections with the material, leading them to question themselves and the world.

While studying Chinese civilization, I also worked at the Centre Audiovisuel Simone de Beauvoir, an institution for archiving and producing films by women, founded in 1981 by Delphine Seyrig, Carole Roussopoulos, and Ioana Wieder. That’s how I met Chantal Akerman. Delphine asked me to help Chantal with the video documentation of the play Letters Home (1984).

I started as a video technician without any training, learning as I went. This was the beginning of my working life, as well as the beginning of the Centre Simone de Beauvoir. We were learning and discovering together. I felt a strong connection to the center’s political focus. I understood and supported the necessity of a space where women come together to create and invent things – but, at the same time, I was a little disturbed by what could be called a positive discrimination. I didn’t want to stay in a protected environment; I wanted to be confronted with the world.

At a certain point, I felt I needed a diploma. But I didn’t want to go to film school and learn art in an academic setting. I just didn’t like the idea of being taught how to think about cinema. So I decided to follow a technical curriculum and enrolled in evening classes at the École Nationale Supérieure Louis-Lumière.

In 1984 I began to work with Chantal, initially on relatively little-known short films. I operated the camera and did the editing. Then I edited Letters Home (1986), a film based on the play through which we had met. During the editing of this particular film, I discovered a calm within myself that I hadn’t previously suspected. I was anxious and indecisive in everyday life, but in those moments I felt an infinite confidence in what was to come. Anxiety often comes from an urge to control outcomes, an urge that is impossible to satisfy and triggers a feverish search for efficacy. I was far from all that. I simply felt I was present.

Chantal would never tell me her intentions. In fact, she often didn’t know ahead of time what she was going to film. She didn’t like to be asked what she was after. “If you’ve found what you’re looking for, it’s no longer worth making a film,” she would say. Her way of making films intersected with my own path: let things happen, respect movement, and don’t force meaning.

I’ve often been asked if Chantal’s work was political. I think that’s obvious. Her films are political, not because they deal with political subjects, but because they set us in motion. They put us directly in relation with the world and ourselves. Chantal didn’t want to copy reality or represent it. She didn’t want to explain anything because explanations prevent questions. In her films, the present and visible resonate with the hidden and invisible. And these resonances, these shifts, open space for thought.

It’s difficult to cite specific film excerpts when you’re talking about editing because it’s a question of rhythm, tension, and resonance over the course of the entire film. A sequence can be composed differently depending on where it falls in the film. It can seem long when seen alone and short when seen in context. Or vice versa. But let’s consider the first ten minutes of Chantal Akerman’s documentary Sud (1999) anyway.

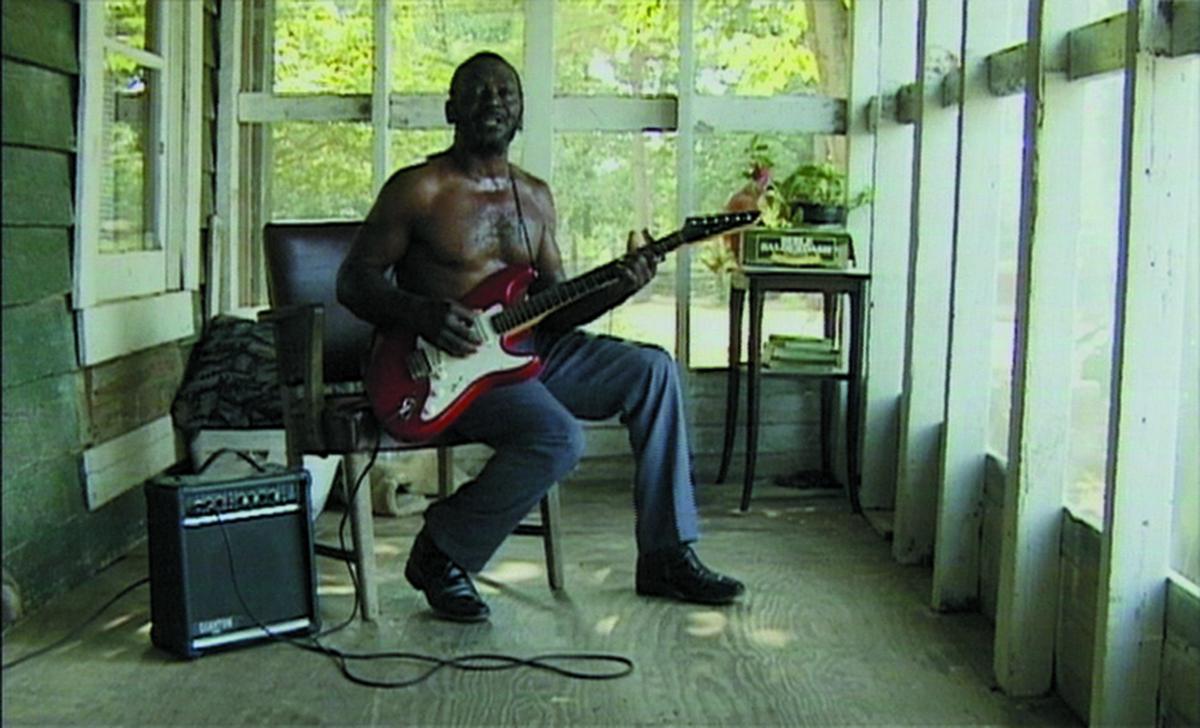

Sud was shot in the American South, and its strength is the dialectic between past and present. Chantal went down there, attracted by Faulkner and Baldwin. The film begins gently, almost peacefully: people talk about how everything seems better now than it used to be. But little by little, in this quiet landscape, you start to feel anxiety. The strident sound of insects becomes threatening, and so do the trees. We begin to hear about slavery and lynching, and then, as the tension grows powerful, we start to question the placidity we saw at the beginning.

Chantal and I often listened to Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit during the editing process. We even considered putting the song in the film. Ultimately, we didn’t even try. But we put in trees – one, two, three of them. When you look at them in the film, you can’t help thinking about hangings. And the shot of prisoners working in a cotton field conjures up the memory of slavery. What guided me during the construction of Sud was Chantal’s extreme attention to the present. We never show or describe the past, but it is dredged up by the present.

Chantal hadn’t planned for the framework of Sud to be the story of James Byrd Jr.’s lynching by white supremacists. Before leaving for what was supposed to be a location-scouting trip, she was only talking about the area’s oppressive landscape and silence. She was practically obsessed. Silence and crickets. But the day she arrived in Jasper, Texas, happened to be the commemoration of James Byrd Jr.’s murder. This became a central sequence in the film.

Sud is not simply a film about the lynching and enslavement of black people in the United States. It’s about the violence of the world and the way history haunts landscapes to become a part of our gaze. By going beyond the categories of good and evil and allowing a space of dignity for each character, including those who speak the most horrible things, the film shakes us directly, questioning our own way of looking at the other and the whole of humanity.

An important part of filmmaking takes place when I discover what’s in the rushes with the director. I watch, listen, and absorb like a photosensitive surface. It’s an intense and fascinating moment, but also exhausting. During this first viewing, I don’t judge. I try to feel what can be constructed. At the same time, I’m also holding myself back, resisting the reassuring temptation to find a structure too quickly and lock in the film. I take notes, always by hand, which helps me return to my first impressions later, as the act of writing has its own history.

Afterward the editing starts, and I always need a moment alone with the material – a few hours, a morning, or a few days. It’s like discovering an unknown space, peculiar because I’m alone with the director’s present absence, guided by intuition and letting a kind of unconscious motion be revealed. People often think when there are two of you it’s hard to make decisions. On the contrary, I feel more freedom when another person is present. Faced with sounds and images alone, you ask, Why am I doing this? Is it even any good? But when you know the other person isn’t far away and will be there later to re-explore and revisit the film, you can free yourself from the question of why.

During editing, words can be dangerous. The film’s momentum can be killed by words that describe intentions, words that precipitate toward a conclusion or claim to see through its mysteries. But some words help – those that suggest and disrupt, that discover fault lines and send us on alternate routes. The words written in my notebook are very simple, often just descriptions – colors, sounds, shapes, sometimes sensations but never interpretations. I don’t like explaining to a director what I’m trying to do because those words affect their perception. I prefer to avoid any preconceived idea, any reasoning that could arise in the director’s mind before discovering the combination of images. That’s why I don’t want the director to look at the timeline, the way so many do today. The important thing is what takes place on screen at the very moment when images and sounds appear. That’s where the film is.

It’s obvious that the relationship between director and editor is based on trust. But trusting each other doesn’t mean you always agree. It means feeling like you’re moving in sync, with the same tension. You stop needing to be self-protective, surrender control, and really listen to yourself, your artistic collaborator, and the images. You let go of certainties and forget decisions in order to allow the film to grow.

It’s hard to explain what guides me when I put one image after another, when I cut a shot or place a sound. I don’t really have a method. What I can say is that, most of the time, I need to start at the beginning. Placing the first shot is like laying the foundation stone of a house; it’s nearly nothing, but at the same time momentous because it’s a birth. There’s nothing, and then there is. Sometimes the first shot is obvious from logging the footage; sometimes it takes a long time to emerge. The beginning of a film opens a space that brings out the subsequent shots.

I like to give myself over to the film’s temporality. I don’t want to know more than the film or to get ahead of it. I like us to discover and move forward together. The more the film grows, the more it’s the film that guides me – as if it existed in and of itself, forging its own path.

That’s why I need to be totally attentive to the material, and sometimes even to lose myself. The images and sounds cannot be twisted and turned, subjected to the necessity or logic of a preplanned meaning. On the contrary, they are living matter that must be listened to, looked at, sculpted, associated, paced, and joined with respect. With respect means without assigning them a role.

I remember editing D’Est (1993) with Chantal. It was like a composition, both in the musical and visual sense. We were sculpting in time and space, looking for the right rhythm. We were editing in the same way Chantal had shot the film, following our intuition, without trying to understand. We said simple things to each other about color, clashes, ruptures, night and day, exteriors and interior, violence, softness, the sound of footsteps in the snow or of tires screeching on icy roads. When we watched the long tracking shots of the faces of people waiting, we talked about their gazes, the slowness of their movements, smiles, beauty, and sometimes sadness. But we never mentioned what these images made us think of. We could feel such associations, but if we had put it into words, the momentum would have slowed, weighing down our actions. We knew without knowing, and that worked for us. Words only appeared a year later, like echoes to the images, when we were editing the installation D’Est au bord de la fiction (1995). These words became those of the installation’s twenty-fifth screen, spoken by Chantal: “Yesterday, today, and tomorrow, there were, there will be, there are at this very moment, people whom history, which no longer even has a capital H, whom history has struck down, people who were waiting there, packed together to be killed, beaten, or starved, or who walk without knowing where they are going, in groups or alone. There is nothing to do. It is obsessive and I am obsessed. Despite the cello, despite cinema. Once the film is finished, I said to myself, so that’s what it was. That again.”

Too often people think that when editing you have to start by working on the narrative and finding the film’s structure, and only then move on to its rhythm by refining the length of the shots and sequences. I find that impossible. That would be like separating content from form, thought from the perceptible. Rhythm is the heart of the film, its breath. It’s also the association of colors, shapes, and lines. Henri Matisse said, “A successful painting is a condensation of controlled rhythms.” The search for the right rhythm is the creation and modeling of an emptiness, both temporal and spatial, in which a network of resonances, secret links, and echoes is gradually created. If the rhythm is right, you can feel tremors, nearly impalpable movements that appear within a shot, and be moved by them without knowing why. These are the emotions that construct the narrative.

Working on rhythm is also listening to absence – in other words, working with images that don’t exist, and without trying to fill the gaps. It’s being wary of the reflex to be exhaustive and to avoid “solutions” aimed at making up for “errors” on the shoot. Sometimes the absence of an image is the central element around which everything is built. Respecting absence as a significant element is putting your trust in unconscious physical action and knowing how to welcome chance.

Editing on celluloid involved a ritual of physical actions that no longer exists today. The need to manipulate the film created a space between physical action and result, which could be called process time. Our hands were busy, but our minds could drift off. We could forget any objective. Digital editing has erased this process time of meditation. Now you click. But you can always recreate a ritual to prevent yourself from going too fast. Get up, walk around, have a coffee, or look out the window. It’s important to create a coming-and-going relationship with the film, to have the time to forget. Otherwise we try and try again, frenetically, until we lose our relationship with the images. I often hear editors say that they’re going to test or approve a version of the edit. You test a light bulb or a battery; you approve an invoice. A film is something you watch, listen to, experience, and question. Maybe I’m putting too much emphasis on their choice of words, but our diction says a lot about us and the time we live in.

My advice is to slow down, to respect the time of artistic creation. Embark on an edit with humility, almost with naivety. This process of deliberate groping around in the dark is what allows the film to go beyond its subject, to stay alive, to continue to move and breathe once it is finished. A living film isn’t locked into a specific meaning but on the contrary free and open, growing and evolving in each viewer, endlessly interpreted and reinterpreted over time, always in motion.

This translation was originally published by BOMB magazine in its 2019 - Summer issue (# 148).

With thanks to Claire Atherton.

Images (1), (3), (4) and (6) from Sud (Chantal Akerman, 1999)

Images (2), (5) and (7) from D'Est (Chantal Akerman, 1993)