Texts

Every Wednesday, Sabzian publishes texts on cinema in Dutch, English or French.Chaque mercredi, Sabzian publie des textes sur le cinéma en néerlandais, en anglais ou en français.Elke woensdag publiceert Sabzian teksten over cinema in het Nederlands, Engels of Frans.

Woman, Arab and... filmmaker. A viable situation? If so, some questions: Is there even one Arab filmmaker who has provoked an explosion of scorn for asserting in front of Marxist militants – don’t laugh – his desire to become a filmmaker? Is there even one Arab filmmaker who was forced to hide from his family that he wanted to make films? Is there even one Arab filmmaker who was called mad by X number of producers for having dared to propose to go and film a guerrilla war? Is there even one Arab filmmaker who has been told from the cradle that he fundamentally wasn’t a “creative” being? To inspire the works of others, fair enough! To write novels dealing with “feminine” subjects is allowed, but barely so (and reluctantly, by the way). But to take the camera in order to talk about human dignity (especially when insisting on women’s liberation), about national dignity? Oh, no, lady! That’s men’s business.

“The Hour of Liberation is, therefore, a partisan film at all levels. In terms of the montage as well: you can’t place images filmed on both sides of the fence in any order, and tell the viewer to choose sides; that would put oppression and freedom, injustice and justice on the same level. The film is constructed on a structure that rejects the bourgeois conception of ‘objectivity’: it clearly takes sides, without necessarily hiding the difficulties of the struggle, without hiding the contradictions, without ultimately lapsing into triumphalism. The entire montage is conceived to produce an analysis of what a people’s war is.”

A year later, when the Germans had lost the war and the concentration camps were liberated, the Allies photographed and filmed the camps, the survivors, and the traces that pointed to the millions murdered. It was above all the images of piles of shoes, glasses, false teeth, the mountains of shorn hair that have made such a profound impression. Perhaps we need images, so that something that is hardly imaginable can register: photographic images as the impressions of the actual at a distance.

Een jaar later, toen de Duitsers de oorlog hadden verloren en de concentratiekampen waren bevrijd, fotografeerden en filmden de geallieerden de complexen, de overlevenden en de sporen die wezen op miljoenen vermoorde mensen. Vooral de beelden van stapels schoenen, brillen en kunstgebitten en de bergen afgeschoren haar maakten een diepe indruk. Misschien moeten er eerst beelden zijn vooraleer iets wat nauwelijks voorstelbaar is indruk maakt, fotografische beelden, afdrukken van de werkelijkheid op afstand.

Harun Farocki in Conversation with Marco Scotini

I try to use a term operational images. This goes back to Roland Barthes in Mythologies, where he says that a non-metaphoric language, an operational language, would be the one that a woodpecker uses: it’s speaking with a tree and not about a tree.

An Interview with Harun Farocki

Conversely, I try to find my words on the editing table. I have both my typewriter and my editing table in one room. It is connected to this question of writing and filmmaking, because it is also very evident you cannot make films the same way you can write a text. For the text you need to go to the library, but 80% or so of them are created in the room, or if not created, then at least the final version is made indoors at your desk. That is also the last stage of the filmmaking, the aspect where writing and filmmaking come together. People ask me, why don’t you write anymore, and I realise it is because I have succeeded in making a form of writing out of my filmmaking.

De surrealisten van het eerste uur, nog vaag vervuld van een dadaïstische geestesgesteldheid, zetten alle zeilen bij en mengden vrolijk disciplines door elkaar om het publiek te verbluffen. Terwijl hun geschriften, theater, muziek en schilderkunst al gauw floreerden, bleef het gebruik van film lange tijd een moeizamere kwestie, in België nog meer dan elders.

Les surréalistes de la première heure, encore confusément habités par l’état d’esprit dadaïste, faisaient feu de tout bois et mélangeaient allègrement les disciplines pour stupéfier les spectateurs. Si l’écriture, le théâtre, la musique ou la peinture trouvèrent vite les moyens de s’épanouir, l’utilisation du cinéma resta longtemps plus laborieuse, en Belgique plus encore qu’ailleurs.

“De mijnwerkers komen uit de mijnschacht tevoorschijn. Ze gaan de straat op, hun gezichten zwart, leerkartonnen helmen op hun hoofd, brandende lampen in hun handen, in dichte rijen die de hele breedte van de straat innemen. Ze naderen met rasse schreden, neuriën een zacht en krachtig gefluisterd lied, voorafgegaan door een zwarte stofwolk.”

« Les ouvriers mineurs remontent de la fosse. Ils s'avancent dans la rue, le visage noir, le casque de cuir bouilli sur la tête, la lampe allumée à la main, en rangs serrés qui prennent toute la largeur de la rue. Ils s'avancent sur un rythme implacable, en chantonnant une chanson murmurée, douce et puissante, précédés d'un nuage de poussière noire. »

Tout le surréalisme est au service de Fantômas.

C’est le seul être au monde avec qui

J’aurais aimé me faire photographier à la foire.

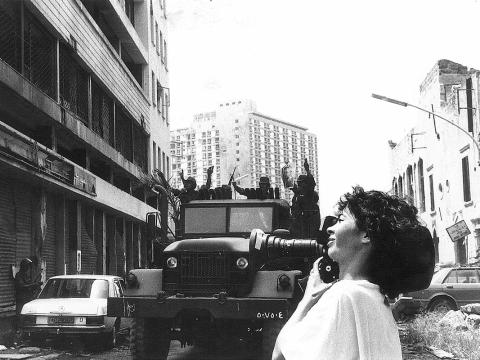

Interview with Jocelyne Saab

“I began by making film reports, documentaries, and I didn’t come to fiction until much later. The boundaries between the two aren’t very clear-cut, however, and there are often documentary elements in fiction films and vice versa. At the time, there was a fabulous reporting tradition, with film crews in conflict zones that didn’t hesitate to take risks and demonstrate a certain situation by bringing us the footage. Resorting to cinema, especially to documentaries, in order to provoke or accompany social change, to denounce or to provide a basis for action, all this was very much present when I started.”

Interview with Jocelyne Saab

“Each time I made a film, it was in a given political period; each time I had a political objective, my films couldn’t just be without orientation. That’s not sentimentality. Through a form of sensibility, a political problem emerges. The destruction of Beirut, the children fighting, it means something. I figured this way of showing things could touch people and have a real political impact. People are fed up with the talking. On television, for example, one day they show a representative of the left, the next a representative of the right. Every day, they agree with someone else, and they end up forgetting who’s right or wrong!”

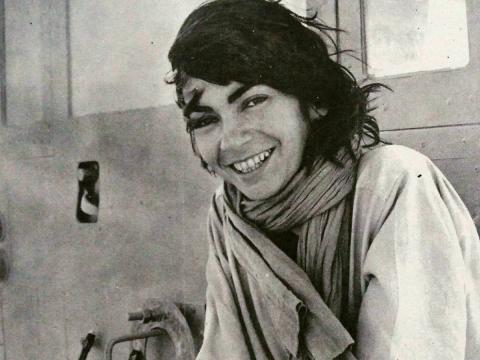

There are encounters that withstand long separations because they happened at a particular time. That goes for you, who I lost sight of for a long time, and who I met in the liveliest days of our lives. Are there lives outside of lively days? Alas, yes. Many years later, we ran into each other and caught up in the queue for a plane from Paris to Cairo, and then in Alexandria we met again, and... since then, we met again where we had parted, in the intimacy of History, the Tunisian revolution had just broken out and our hearts were cheerful.

“They no longer allowed us to express ourselves. There was no freedom anymore. At the time, I didn’t fully understand that I was scaring them because I didn’t realize the impact of my work. With my documentaries and my different way of looking at things, I managed to reach European and American television channels. They were afraid my images would shake the public opinion and dismantle their propaganda.”

I would also like to express my affection for Jocelyne. On the strength of her films and the way she has lived her life to date, I consider her one of the bravest, most intelligent and above all freest spirits I have ever encountered – though her freedom of thought and behaviour has sometimes cost her dearly and even put her life in danger. Few other people have suffered so much to preserve their self-esteem and survive in a meaningful way in a world as hostile and indifferent as ours.

Interview with Jocelyne Saab

“Today, nine years later, I say to myself: “It’s no longer a matter of taking a position.” That’s where my films are headed and that’s what brings me to fiction. I think I’m meeting my time, the wave of complete scepticism, of doubt, which means that in the fiction to come I have completely abandoned any political point of view – even if everything is political. Even if there is no doubt that there has been a political position. The desire I had to be on TV, to reach a lot of people, meant that my work was concerned with the imagery, which was much more powerful than militant film.”

Interview with Jocelyne Saab

“This documentary phase wasn’t only linked to my personal history; it was determined by my country’s political situation and Lebanon’s cinema history. My trajectory is a bit like that of other Lebanese filmmakers. If I decided to move to fiction it’s because, after speaking in a “militant” manner, I now want the image to speak as much as possible.”

What does it mean to make a film when you are a woman, an Algerian, a novelist (writing in French) and you decide to make it in your own country, for the people of that country, with the widest distribution possible, as it is a film for television?

Élie Faure tells us that the aging Renoir, when he used to refer to this light in Women of Algiers, could not prevent large tears from streaming down his cheeks. Should we be weeping like the aged Renoir, but then for reasons other than artistic ones? Evoke, one and a half centuries later, these Bayas, Zoras, Mounis, and Khadoudjas. Since then, these women, whom Delacroix – perhaps in spite of himself – knew how to observe as no one had done before him, have not stopped telling us something that is unbearably painful and still very much with us today.

A slow pace, silence, memory regained, sensuality, Assia’s film tried to lead us far away from our noisy and dogmatic present. It tried to make us seize the intimacy of secluded women in unusual ways. The language of shadows, the language of bodies. The film is set somewhere between Cherchell and Tipaza. The beauty of the locations takes the story to a realm of mythological enchantment while leaving intact the realism of the existential wound that is buried beneath the silence of the characters.

Two interviews with Assia Djebar

“I started from the idea that the more a woman is traditional, the less she needs an association with folklore in terms of sound. When you come across the image of a person whose clothes and attitude are very “conservative”, there’s no need to associate this person with flutes or tambours. At the end, during the party in the caves, the women dance while singing the most ordinary songs, popular street songs really, and I linked this to the fourth dance of Bartók’s “Dance Suite”. I thought it emphasized the inherent nobility of these women. I got the impression that it was original music, written especially for this moment!”

Can it be simply by chance that most films created by women give as much importance to sound, to music, to the timbre of voices recorded or captured unawares, as they do to the image itself? It is as though the screen had to be approached cautiously and be peopled, if need be, with images seen through a look, even a short-sighted, hazy look, but borne on a full, commanding voice, hard as stone but fragile and rich as the human heart.

To give a rhythm to the images of reality for twenty years of everyday life in the Maghreb, where each of the three countries has paid its death toll to obtain its independence. This work, which should be a simple “historical” visualization, I approach as a mined area. I apprehend it as an explosive that awakens from my past, from any past, the engulfed pains we believe to be rotten or defeated, I don’t know. They come alive again, they dress again as faceless ghosts, but veiled, as if they suddenly demanded the unfolding of a purifying liturgy.

Assia Djebar’s treatment for La Zerda et les chants de l’oubli [The Zerda or the Songs of Oblivion] (1978-1982): “Without any comment, however, shortly before and during the credits, three known paintings by Delacroix unfold in long shots and in slow pan shots that focus on details of characters, horses or costume elements, each of the paintings linked to an atmosphere of music and fantasia from the pre-colonial Maghreb.”

So your film is more a film about space than about women?

Yes, because saying that my film is a film about women doesn’t mean anything. I’ll always make these films... Female bodies, women are my subject. Like a sculptor somehow, who uses a certain material, while another sculptor will use another material. That should mean something, shouldn’t it? I think that’s what the Cinémathèque audience couldn’t stand; I’ve removed men from my film. But what can I say, except that I’ve just shown what exists in reality. I intentionally separated the sexes in the image, as in reality. The intention is feminist, and why not? I wanted to show the number one problem of Algerian women, which is the right to space. Because I was able to verify that the more space the women had, the firmer they stood.

De romance van de Derde Weg

De politieke zelfgenoegzaamheid van de jaren ’90 leverde een verrassend groot aantal mainstream Amerikaanse romantische komedies op over het verzet tegen de gevestigde macht. Maar You’ve Got Mail bracht ons een nieuwe fantasie, volledig geneoliberaliseerd: wat als de gevestigde macht de ware is?

I would like to define the intricate relationship between my cinematographic language and the prevalent political language. The prevalent political language aims at determining a harmony of concrete interests. It is a uniform language that emphasizes the difference between what is similar and what is different within a very precise geographical and economical area. On the other hand, my cultural action, and not cultural language, aims at liberating spaces where everyone can be moved, can rediscover the real nature of things, marvel at the world, think about it and immerse oneself in the world of childhood. Finally, politics excludes the imaginary, unless it can be used for ideological or partisan ends. But my films’ cultural world is made up of both reality and the imagination, both of which are vital to the creation of my films. It is like a child’s quest for identity: he or she needs these two levels – reality and dream – to approach life in a balanced and non-schizophrenic way.

[J]e voudrais définir la relation complexe qui existe entre mon langage cinématographique et le langage politique dominant. Le langage politique dominant vise à déterminer une harmonie d’intérêts concrets. C’est un langage uniforme qui souligne la différence entre ce qui est similaire et ce qui est différent dans une zone géographique et économique très précise. D’autre part, mon action culturelle, et non le langage culturel, vise à libérer des espaces où chacun peut être ému, peut redécouvrir la nature des choses, s’émerveiller du monde, y penser et s’immerger dans le monde de l’enfance. Enfin, la politique exclut l’imaginaire, à moins qu’il ne puisse être utilisé à des fins idéologiques ou partisanes. Mais le monde culturel est constitué à la fois de réalité et d’imagination, deux éléments essentiels à la création de mes films. C’est comme une quête d’identité pour un enfant : il a besoin de ces deux niveaux – réalité et rêve – pour aborder la vie d’une manière équilibrée et non schizophrénique.

“Yes, from a filmmaker’s point of view, we wanted to look for images other than those brought back by television crews every time there’s a political event in the occupied territories (manifestations, strikes, riots, etc.). We actually believe that these images make us forget the essence: the sense of the struggle of these people. The informative television images are images of ‘effects’, and we are looking for images of ‘causes’.”

« Oui, notre point de vue de cinéastes était de rechercher des images autres que celles ramenées par les équipes de télévision à chaque événement politique dans les territoires occupés (manifestations, grèves, émeutes, etc.). Nous croyons, en effet, que ces images finissent par faire oublier l’essentiel : le sens de la lutte de ces gens. Les images d’information télévisées sont des images d’« effets », nous recherchions des images de « causes ». »

“[Fertile Memory] is the result of several years of work. I made several reports in the occupied territories, but I also have to say that the film was beyond me. The Palestinian question is basically an issue of oppression: an oppression that dominates the world. I said to myself that I would be able to give the Palestinian question a new dimension by talking about the most oppressed. I thought that women would help bring out all the contradictions.”

[C]’est le résultat de plusieurs années de travail, j’ai fait plusieurs reportages dans les territoires occupés, mais je dois dire aussi que le film m’a dépassé. Au fond, c’est quoi le problème palestinien, c’est le problème de l’oppression : une oppression qui domine le monde. Je me suis dit que c’était en parlant des plus opprimés que je parviendrai à donner une dimension au problème palestinien. J’ai pensé que la femme permettrait de faire ressortir toutes les contradictions.

A Budding Filmmaker Generates a Past With a Future

The source that irrigates Fertile Memory springs from two poles that constitute the foundations and permanence of the Palestinian soul: usurped land and women. Few films show daily life in the physical and temporal reality (32 years for Mrs Farah Hatoum) of the Israeli occupation. And if these films exist, their lack of credibility is such that at best, we make do with imagining the thoughts behind the gestures and gazes – the deepest dimension of which only the prism of culture will render.

Un cinéaste en germe génère un passé chargé d’avenir

La mémoire fertile jaillit de deux pôles qui constituent les fondements et la pérennité de l’âme palestinienne : la terre usurpée et la femme. Rares sont les films qui donnent à voir le quotidien vécu dans la réalité physique et temporelle (32 ans pour Mme Farah Hatoum) de l’occupation israélienne. Ou, lorsque ces films sont, leur non-crédibilité est telle qu’on se contente dans le meilleur des cas, de deviner les pensées qui habitent gestes et regards et que seul, le prisme de la culture, nous restitue dans leur dimension profonde.

It is Khleifi’s achievement to have embodied certain aspects of Palestinian women’s lives in film. He is careful to let the strengths of Farah and Sahar emerge slowly, even if at a pace that risks losing the film the larger audience it deserves. He deliberately disappoints the expectations engendered in us by the commercial film (plot, suspense, drama), in favor of a representational idiom more innovative and – because of its congruence with its anomalous and eccentric material – more authentic.

Khleifi a réussi à incorporer au cinéma certains aspects de la vie des femmes palestiniennes. Il prend soin de laisser les forces de Farah et Sahar émerger lentement, même si c’est à un rythme qui risque de perdre le grand public qu’il mérite. Il déçoit délibérément les attentes suscitées en nous par le film commercial (intrigue, suspense, drame), en faveur d’un langage de représentation plus innovant et, du fait de sa congruence avec son matériel irrégulier et excentrique, plus authentique.

Dimanche par Edmond Bernhard, 1963

Film inclassable qu’aucune étiquette – ni « documentaire », ni « essai », ni « film expérimental » – ne suffit à désigner puisqu’il les recouvre toutes de son absolue singularité, Dimanche est un film unique et rare apparu de manière impromptue sur le terrain en jachère d’un cinéma belge qui ignorait encore, au début des années soixante, qu’il pouvait devenir « moderne ».

“There’s something crazy about editing. The little I learned about film technique and the manipulation of forms comes from editing really. Because I had to edit everything myself; I couldn’t afford an editor – and I didn’t want one anyway. I was too – what word do they use nowadays? – “invested”. Funny word.”

Le montage a quelque chose de fou. Ce que j’ai un peu appris de la technique de cinéma et de la manipulation des formes me vient réellement du montage. Parce que j’ai dû tout monter moi-même ; et n’avais pas de quoi m’offrir un monteur – du reste, je n’en avais pas envie. J’étais trop - comment dit-on maintenant ? – investi. Drôle de mot.

“Nothing can fix the finite which lies between the two infinities that enclose and flee from it.” This formula by Pascal may very well apply to the films of Edmond Bernhard, the most brilliant filmmaker Belgium has ever known. His entire oeuvre essentially consists of five short films made between 1954 and 1972, less than two hours of screening time in total: Lumière des hommes (1954), Waterloo (1957), Belœil, ou Promenade au château de Belœil (1958), Dimanche (1963) and Échecs (1972).

« Rien ne peut fixer le fini entre les infinis qui l'enferment et le fuient. » Cette formule de Pascal peut fort bien s'appliquer aux films d'Edmond Bernhard, le plus génial cinéaste que la Belgique ait connu. Son œuvre entière tient essentiellement en cinq courts métrages réalisés entre 1954 et 1972, qui totalisent moins de deux heures de projection : Lumière des hommes (1954), Waterloo ( 1957), Belœil, ou Promenade au château de Belœil (1958), Dimanche (1963) et Échecs (1972).

With nimble-fingered virtuosity, he operated an array of objects arranged around his piano: fake pistols for crime-of-passion gunshots, castanets to imitate the sound of horses’ hooves, grains of lead sliding over a canvas for the sound of waves, buckets of water and sponges for the sound of raindrops. From high up in my little room across the street, I could hear the sounds of the piano, which allowed me to understand what kind of film it was: a farce, a bourgeois drama, a romantic comedy, or even a violent storm at sea or bolting horses at a gallop.

A Film by Chantal Akerman

The day I decided to think about the future of cinema, I told myself I wouldn’t live to see it. I asked myself if the future is always in front of us. So I looked ahead, then I turned around.

Hatari! is an enormous film, one which is only saved from its monstrosity by the incredible intelligence of its director. It is a summation in which all the aspects of cinema are stirred together, amalgamated. The labyrinthine complexity of its construction is dizzying. Watching it can only put one off, or leave them wiped out.

Met Dirk Lauwaert in het klaslokaal en de filmzaal

Ik kan nog zoveel regels afkondigen en (proberen te) handhaven, nooit kan of wil ik de gedachten van de student controleren. Uit het raam staren is een recht van elke leerling. De aula mag dan geen vensters hebben en de digitale verbinding met de buitenwereld mag dan tijdelijk zijn verbroken, niets verhindert de student (of bioscoopganger) te dagdromen, in gedachten boodschappenlijstjes op te stellen, creatieve projecten of amoureuze plannen te smeden, familiale, financiële, lichamelijke of mentale problemen te overpeinzen terwijl ik vooraan mijn best doe. Of terwijl de film zijn ding doet. Net zoals de film poog ook ik niets te bewijzen, niemand te overtuigen. Ik wil geen zieltjes maar aandacht winnen. Hier en nu.

Into the Classroom and the Cinema with Dirk Lauwaert

Herman Asselberghs is currently working on a long-term film project at the film department of the LUCA School of Arts, where he has been teaching for two decades. Through the realization of a film essay, he probes the relationship between attention and distraction in the film theatre and the classroom. Throughout the creation process, Sabzian reports on his accompanying reading and writing. On a regular basis, Asselberghs selects an existing text that interests him and that he himself provides with an accompanying text. In this second instalment, he probes possible overlaps between teaching and film-watching by means of Berichten uit een klas [Reports from a Classroom], Objectieve Melancholie [Objective Melancholy] and other key essays by the Belgian critic Dirk Lauwaert. He also reminisces about Lauwaert’s overlooked Filmparties.

The Film That Won’t Be Shown at the Cannes Festival: Farrebique

Much of the poetry emerging from this film emanates from what is not said, from the faces of those whose inner lives are only to be guessed. Only a director permeated with the life of farms and fields could have achieved this tour de force.

“I already knew that you can’t just make a film overnight with people who aren’t actors. Especially when you want to make a feature film. And there I was, plunging into a spoken feature-length film. Some friends had told me, “Be careful!” I responded, “Damn it! Flaherty made Nanook, and he made Moana!” “Ah yes, okay, but that’s silent film! You, your peasants, when they open their mouths, you’ll see, it’ll be a catastrophe.” I hung on all the same. Of course, you can’t make them play Le Cid or Hamlet... You have to make them play something that’s closer to their hearts.”

Farrebique by George Rouquier

That is why this film is a great work of art. After all, the eternal can only be reached through the present: the best chance to stand the test of time is to radically be a child of your time.

Reflections on a Polemic

The film was barely finished, and the “Farrebique affair” began – the selection committee of the first Cannes Film Festival eliminated the film from the competition […]. “That Farrebique will not be going to Cannes is an outright scandal,” Maurice Bessy declared [...]. “Although some reservations could be made about the arbitrary conception of the subject,” wrote Georges Sadoul, “Farrebique clearly had its place at the festival, whereas the particularly incontinent logorrhea of A Lover’s Return should have been refused even a back seat.” But the screenwriter of this last film, Henri Jeanson, was the very committee member who fought for the rejection of Farrebique, although he denies that: “Farrebique was not presented to us for approval. I am, admittedly, one of those who find this film boring. I don’t consider cow dung to be photogenic material. I agree that I may be wrong, but I protest against those who claim in bad faith that Farrebique was rejected.”

There’s no lack of so-called realist films, whether they are news stories or slices of life. There’s not even a lack of peasant films. Why is Farrebique the odd one out? That’s where, for me, Rouquier’s genius comes in, his egg of Columbus. He understood that verisimilitude had gradually taken the place of truth, that reality dissolves in realism. He painstakingly set out to discover it, to bring it back to light, to bring it up naked from the well of art.

Wij zien geen toekomst in een stiefmoederlijk beleid dat “scherpe” keuzes maakt, er is integendeel dringend nood aan zorgzame en correcte ondersteuning van alle bestaande initiatieven. Wij zijn van mening dat een voldragen en divers filmlandschap zich enkel blijvend kan manifesteren wanneer dat gepaard gaat met de ontwikkeling van een scherpzinnige en diepgaande filmkritiek. Red de filmcultuur, investeer in filmkritiek!

To Make Images Speak

TV-programme producers occasionally try to make their works available for repeated viewing in addition to one-off screenings. As is the case with Voyage à Paris, which is like a beautiful poem you want to read several times, or a piece of music you want to hear several times. This visual essay contains a couple of passages you will remember especially well, transitions that are so intriguing that you will want to further savour them.

As part of its 1971–1972 programme, the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven has planned an exhibition on the street as a form of visual environment. The museum thus becomes part of an international trend that manifests a renewed interest in the street as a living environment.

Op stilistisch vlak is de film [Abdij van het Park Heverlee] enigszins verwant aan de aanpak die Alain Resnais voorstond in L’année dernière à Marienbad. Zelf heeft Cornelis de relatie gelegd met de werkwijze van Alexandre Astruc en diens zogenaamde Caméra-Stylo. “Net zoals Astruc zoek ik hoe je iets opbouwt, zoek ik naar ritmes”, aldus Cornelis.

Stylistically, Cornelis’ approach [in Park Abbey Heverlee] is somewhat similar to the method used by Alain Resnais in L’année dernière à Marienbad (1961). Cornelis himself pointed out a connection to Alexandre Astruc’s so-called Caméra-Stylo. “Like Astruc, I seek ways to build up to something; I seek rhythms,” explains Cornelis.

On four minutes of Godard

Godard doesn’t even consider turning Bardot into a character shattering the stereotypical image the mass media make of her. He presents Bardot as ‘Bardot’. He cites the phenomenon Bardot, uses it as a kind of ready-made, without irony. And because the mass media associate the name Bardot with ‘nudity,’ he promptly presents her naked. It is as if Godard is saying to the audience: “You came to watch a film with Bardot? Here she is in her entirety, totalement, naked like Urbino’s Venus.”

Over vier minuten Godard

Godard denkt er niet aan om van Bardot een personage te maken dat het stereotype beeld dat de massamedia van haar ophangen, doorbreekt. Hij voert Bardot als ‘Bardot’ op. Hij citeert het fenomeen Bardot, gebruikt het als een soort readymade, zonder enige ironie. En aangezien in de massamedia de naam Bardot geassocieerd is met ‘bloot’, voert hij haar ook meteen bloot op. Het is alsof Godard tegen het publiek zegt: “Je komt naar een film met Bardot kijken? Hier heb je haar meteen helemaal, totalement, naakt als de Venus van Urbino.”

Naar aanleiding van de restauratie van Agnès Varda’s Le bonheur (1965) in 2023 herpubliceerde Sabzian Eric de Kuypers kritiek van de film, oorspronkelijk verschenen in het cultureel-maatschappelijk maandblad Streven. Voor deze gelegenheid voorzag de Belgische filmmaker en auteur zijn kritiek van een nieuw commentaar. Eric de Kuyper: “Voor zover ik mij herinner was de receptie van Le bonheur nogal controversieel, met voornamelijk ethische pro- en contracriteria. Een effect dat Agnès Varda vanzelfsprekend had nagestreefd. Mij leek dat een valkuil. Varda verpakte haar film in een nogal extreme vorm van esthetiek. Dit was te mooi om waar te zijn!”

La momie de Chadi Abdel Salam

Votre film est donc avant tout une réflexion sur Je destin d’une culture nationale ?

Bien entendu. La trame policière de l’histoire ne m’a servi que de prétexte. Par ailleurs, La momie est un film que j’ai senti, et donc construit, à plusieurs niveaux.

Shadi Abdel Salam carried two cultures within him: he was born and raised in Alexandria, and his mother and maternal ancestors came from Al-Minieh. He travelled in two worlds: that of the cosmopolitan city of Alexandria and its rich Hellenic heritage, and that of Al-Minieh, the pearl of Upper Egypt, imbued with traditions and customs drawing their rigidity from distant pharaonic origins. Although he looked like a noble cavalier, with matching gentleman-like qualities, fluent in English, French and Italian, he always remained that austere son of Upper Egypt, linked to his ancestors who lie inside the tombs dug into the hills of Thebes by a very long history.

On 16 December 1969, The Mummy was shown for the first time to the audience of the Cairo Film Club, which included many intellectuals. In the dark, Shadi Abdel Salam waited for the reaction of his family and friends to this new work of art. All were moved by the film’s sober technique and by its theme, which was deeply touching for Egyptians: a sacred theme presented in a new form – the language of film – and accompanied by the sincerity that’s in harmony with this people.

The Mummy by Shadi Abdel Salam

So, your film is above all a reflection on the destiny of a national culture?

Absolutely. The crime narrative was just a pretext. Besides, The Mummy is a film that I felt, and therefore constructed, on various levels.

Shadi Abdel Salam’s Words

A biographical chronicle of Egyptian screenwriter, costume and set designer, and filmmaker Shadi Abdel Salam (1930-1986) narrated by means of a collection of excerpted interviews.

“I am from both Upper Egypt and Alexandria … the son of conservative families from Minya and Alexandria. My father was a lawyer, a man of the law … My name is Shādī Muhammad Mahmūd ‘Abd al-Salām.”

A Screenplay by Shadi Abdel Salam

Shadi Abdel Salam’s entire screenplay for Al-mummia [The Mummy] (1969), also known as The Night of Counting the Years.

“Long pan of the Pennedjem Papyrus showing: the god Anubis; the two goddesses Isis and Nephtys; five wailing women; a mummy inside a shrine over a sledge before whom two priests offer a piece of meat and other offerings; and lastly the mummy, with the Jackal-headed Anubis standing behind it. Interior. Night. Corner, Cairo Museum, Summer 1881 A.D.”

Drawings sketched by Shadi Abdel Salam in preparation for his film Al-mummia [The Mummy] (1969), also known as The Night of Counting the Years.

The Films I’ve Made and Don’t Exist

If I don’t film, I don’t see anything, I don’t remember anything, neither trees nor faces. If I film them, I can forget them. My film is my memory, a catalogue of facts and gestures, a (very incomplete) inventory of my life.

“My films are like fables, and reality is their backdrop. They imitate the simple form of a diary, they are autobiographical, since they often deal with a quest for identity and a search for origins, and I often appear in them as a subject and as a character.”

Film is (and this is my fundamental assumption) not art in the bourgeois-humanist sense of the word. It is an industry and a very important part of the so-called culture industry at that. Those who switch from the category of art to the category of culture industry ultimately make a political-ideological choice, the consequences of which can hardly be overrated.

Aantekeningen over Lovers Rock, december 2020

In Lovers Rock (2020), McQueens zelfverklaarde “musical” gebaseerd op zijn jeugdherinneringen aan Londense “blues parties”, neemt de roep van de vervoering de allure aan van een hymne. Wanneer, op de wulpse tonen van Janet Kays Silly Games, lichamen zich gracieus in beweging zetten en elkaar aftastend beroeren, vult de ruimte zich met een peilloze hunkering. Maar als de muziek zachtjes wegdeemstert en een woordeloos akkoord wordt gesloten om dat gevoel collectief verder te zetten, wordt het lied a cappella opnieuw ingezet: “I’ve been wanting you / For so long, it’s a shame / Oh, baby.”

Al te vaak denkt men dat men in de montage eerst de structuur van de film moet uitwerken om het verhaal op poten te zetten en daarna het ritme bepaalt door de duur van de sequenties op elkaar af te stemmen. Dat is voor mij onmogelijk. Het zou de inhoud loskoppelen van de vorm, de gedachte van het gevoel. Ritme is het hart van het werk, het is er de adem van. Het is ook het samenbrengen van kleuren, vormen en lijnen.

Trop souvent on pense qu’en montage il faut d’abord travailler la narration en trouvant la structure du film, puis le rythme en affinant les durées. Pour moi c’est impossible. Ce serait comme dissocier le fond de la forme, la pensée du sensible. Le rythme, c’est le cœur d’une œuvre, son souffle. C’est aussi l’association des couleurs, des formes, des lignes.

Too often people think that when editing you have to start by working on the narrative and finding the film’s structure, and only then move on to its rhythm by refining the length of the shots and sequences. I find that impossible. That would be like separating content from form, thought from the perceptible. Rhythm is the heart of the film, its breath. It’s also the association of colors, shapes, and lines.

In Akermans installatie Marcher à côté de ses lacets dans un frigidaire vide (2004) neemt het woord niet enkel de ruimte in, het wordt beeld. Het vervangt de afwezigheid van het beeld.

Brussel-transit is ontegenzeglijk een autobiografisch verhaal. Niet helemaal documentair, noch helemaal fictief, niet helemaal het heden, noch helemaal een reconstructie neemt de film zowat al die vormen aan, maar ook iets ondefinieerbaars en ongrijpbaars dat met de herinnering te maken heeft.

Bruxelles-transit relève sans conteste du récit autobiographique. Ni tout à fait documentaire ni tout à fait fiction, ni tout à fait présent, ni tout à fait reconstitué, il prend corps d'un peu tout cela, mais aussi de quelque chose d'indéfinissable et d'impalpable qui tient du souvenir.

Bruxelles-transit is grotendeels autobiografisch en begint als een quasi-documentaire film waarin de acteurs (of actants) niet meer dan silhouetten zijn die in het zwart-witte (meer zwarte dan witte) stationslandschap zijn geplaatst, de plaats of non-plaats bij uitstek van de oorsprong van reizen en ballingschap, van de hier zo symbolische transit uit het verhaal van Samy’s ouders, die uit Polen kwamen met een visum voor Costa Rica.

Largement autobiographique, Bruxelles-transit commence comme un film quasi documentaire, où les acteurs (ou actants) ne sont que des silhouettes placées dans le paysage noir et blanc (plus noir que blanc) de la gare, lieu ou non-lieu par excellence de l’origine du voyage et de l'exil, du transit ô combien symbolique ici de l'histoire des parents de Samy venus de Pologne avec un visa pour le Costa Rica.

Een interview over Victoria (Isabelle Tollenaere, Liesbeth De Ceulaer, Sofie Benoot, 2020)

Parallel aan hun autonome filmprojecten werkten de documentairemakers Sofie Benoot, Liesbeth De Ceulaer en Isabelle Tollenaere jarenlang samen aan een film die zich afspeelt in de Amerikaanse woestijn. Victoria is gegroeid uit een voortdurende dialoog tussen drie filmmaaksters die ervoor kozen om samen een weg tot het einde af te leggen. Op een reis door de woestijn ontmoetten ze Lashay. Hij treedt op als gids doorheen een landschap waar de levens van uiteenlopende woestijnbewoners met elkaar verknoopt zijn. De Ceulaer: “Victoria bestaat uit verschillende lagen die we met elkaar wilden verweven, zoals de relatie van Lashay met California City en Los Angeles of de verschillende aspecten van Lashays persoonlijke situatie. Het was een enorme opgave om tot deze structuur te komen, ook al lijkt die zo eenvoudig.”

Zowel de openingsfilm van Film Fest Gent 2018, Girl van Lukas Dhont, als de slotfilm, Beautiful Boy van Felix Van Groeningen, waren gebaseerd op waargebeurde verhalen. De eerste is het relaas van een jonge transvrouw, de tweede dat van een jongeman die met een drugsverslaving worstelt.

“The real is what is. It sounds simple. And yet, if we try to define it, we are struck by dizziness. The question likely is how do we humans relate to what is? ”

« Le réel, c’est ce qui est. Cela paraît simple. Et pourtant, si on essaie de le définir, on est pris de vertige. La question est sans doute : comment nous, humains, pouvons-nous être en relation avec ce qui est ? »

“De werkelijkheid, dat is wat is. Dat klinkt eenvoudig. En toch, als we haar proberen te definiëren, worden we er duizelig van. De vraag is waarschijnlijk hoe wij, mensen, in contact kunnen treden met wat is?”

Un texte écrit et lu par Claire Atherton lors de la soirée hommage à Chantal Akerman à La Cinémathèque française, avant la projection en avant-première de No Home Movie (2015). Atherton : « J’ai envie de vous parler de Chantal. De vous dire tout ce qu’elle m’a donné, tout ce qu’elle m’a appris, tout ce qu’on a partagé. De vous raconter comme elle était, lumineuse, intelligente, surprenante, et drôle aussi... »

A text written and read by Claire Atherton during the homage to Chantal Akerman at the Cinémathèque Française on 16 November 2015, before the premiere screening of No Home Movie (2015). Atherton: “I want to speak to you about Chantal. To tell you everything she gave me, everything she taught me, everything we shared. To tell you how she was: luminous, intelligent, surprising, and funny too …”

Claire Atherton las deze tekst voor op de avond ter ere van Chantal Akerman in de Cinémathèque Française op 16 november 2015, voor de vertoning van No Home Movie (2015). Atherton: “Ik wil het met jullie over Chantal hebben. Ik wil jullie vertellen over alles wat ze me gaf, alles wat ze me leerde, alles wat we deelden. Jullie vertellen hoe ze was, lumineus, intelligent, verrassend en ook grappig ...”

Christopher Nolans Tenet

Tenet is zowel Nolans beste als slechtste film. De beste, omdat de regisseur hier voor het eerst ten volle zijn eigen holle doos lijkt te omarmen; maar ook de slechtste, omdat net die resten van het inhoudelijke de film uiteindelijk tot de nederlaag veroordelen. De formalist die niet uit de kast wilde komen, of de pornograaf die geen porno durfde te maken: ziedaar de formule van Tenet.

Christopher Nolan's Tenet

Tenet is both Nolan’s best and worst work to date. The best, because the film is his first earnest embrace of his hollow box, his first explicit love letter to emptiness. But it is also the worst, because it is precisely those remnants of content which ultimately condemn the film to its defeat. Nolan is the formalist who dared not speak his name, a manqué mannerist, afraid that the day of his outing would also be his last. The pornographer who would not make porn: this is Tenet’s formula.

Jean Renoir’s The River

André Bazin is sometimes called “the inventor of film criticism”. Entire generations of film critics and filmmakers, especially those associated with the Nouvelle Vague, are indebted to his writings on film. Film opens a “window on the world”, according to Bazin. His writings would also be important for the development of the auteur theory. Bazin: “Jean Renoir was unquestionably our greatest director. The past tense that has just flown out of my pen here does not mean – thank God! – that Renoir has passed away, only that he is no longer ours.”

Le fleuve de Jean Renoir

André Bazin est parfois appelé « l’inventeur de la critique cinématographique ». Des générations entières de critiques et de cinéastes, notamment ceux associés à la Nouvelle Vague, sont redevables à ses écrits sur le cinéma. Le film ouvre une « fenêtre sur le monde », selon Bazin. Ses écrits sont également importants pour le développement de la politique des auteurs. Bazin : « Jean Renoir était sans conteste notre plus grand metteur en scène. L’imparfait qui est venu sous ma plume ne signifie point, Dieu merci ! que Renoir a disparu, mais seulement qu’il cessa d’être nôtre. »

The River van Jean Renoir

André Bazin wordt weleens de “uitvinder van de filmkritiek” genoemd. Hele generaties filmcritici en filmmakers, niet in het minst die verbonden met de Nouvelle Vague, zijn schatplichtig aan zijn schrijfsels over film. Film opent een “venster op de wereld”, aldus Bazin. Zijn geschriften zouden ook belangrijk zijn voor de ontwikkeling van de auteurstheorie. Bazin: “Jean Renoir was ontegenzeglijk onze grootste regisseur. De verleden tijd die hier uit mijn pen rolt betekent godzijdank helemaal niet dat Renoir is omgekomen, enkel dat hij niet meer van ons is.”

De gerestaureerde versie van Chantal Akermans Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) liet me toe een detail op te merken dat me nog niet eerder was opgevallen. Door het beeld te bevriezen herkende ik het omslag van het boek dat Jeannes zoon Sylvain aan het lezen is. Het boek is meer dan een gewoon rekwisiet want de jongen gaat volledig op in het werk en grijpt elke gelegenheid aan om verder te lezen. Wat moeten we aanvangen met de haast onzichtbare, verborgen, mysterieuze aanwezigheid van dit object of verhaal in de film? Het zou te ver gaan om het boek te beschouwen als een mise en abyme van de film, maar het kan in deze tekst wel dienen als een sleutel om te onderzoeken in welk picturaal universum Sylvian en zijn moeder precies vastzitten.

Pedro Costa’s Vitalina Varela

Ventura, who had only played himself in previous films, appears in Vitalina Varela as a full-blown actor, playing against type a double role taken from the world of fiction: a fallen priest character distantly echoing Bernanos’s and Bresson’s miserable country priest; but also a privileged witness of the life of the deceased, a witness behind whom one sometimes seems to perceive the wandering shadow of Joseph Cotten/Leland in his retirement home, even though Citizen Kane is not part of Pedro Costa’s pantheon.

Vitalina Varela van Pedro Costa

Ventura, die in eerdere films alleen zichzelf speelde, verschijnt in Vitalina Varela als een volwaardige acteur die een dubbelrol speelt die niet bij hem past en die ontleend is aan de wereld van fictie: een gevallenpriesterpersonage dat doet denken aan de ellendige plattelandspriester van Bernanos en Bresson; maar tegelijkertijd ook een bevoorrechte getuige van het leven van de overledene, achter wie men soms de schaduw van Joseph Cotton/Leland in het bejaardentehuis denkt te zien rondwaren, ondanks het feit dat Citizen Kane niet tot het pantheon van Pedro Costa behoort.

Gesprek met Eric de Kuyper

Eric de Kuyper: “Pink Ulysses is een duidelijke confrontatie, het resultaat van mijn studie van het surrealisme, van de droom, van het gebruik van kitsch, het gebruik van symbolen. Vroeger zou ik nooit zo een roos hebben durven of willen gebruiken, nu heb ik het gewoon gedaan. Het is die houding van: laten we eens even kijken of dat niet kan, of we er niets mee kunnen doen.”

Plezierige didactiek en verscheurend hedonisme

Eric de Kuyper wil niemand overreden of bekeren, maar wel de vlam van de passie ook bij anderen aanwakkeren; om plezier te beleven. Geen platvloerse pret, maar de gesofisticeerde, Barthesiaanse notie van ‘le plaisir’: “Het opnieuw pogen te beseffen dat datgene waar het bij kunst uiteindelijk om draait het esthetische genot is. Het is opnieuw het recht opeisen om te zeggen: “Ik hou van”. Het is beseffen dat ik recht heb op ‘smaak’ en dat ik daarvoor de geldende normen wel eens moet doorbreken.”

The 91 year-old Michael Snow is one of the few canonized figures of his ilk, and the structural school he’s said to be part of remains etched into the annals of American cinematic history. Over two conversations, Snow and Brandon Kaufman spoke about [...] retrospection, as well as process, legacy, and experimentation – and the contradictions therein. Michael Snow: “each of my films is different and each film has a different quantity of narrativity. Speaking structurally, narrativity means presenting an event to the audience at a particular time, then referring to that event later. I have tried to control "narrativity" in different ways, trying to get [the film] situated in the ideal “now” of the cinema experience.”

Op 24 augustus 2020 overleed Robin “Robbe” De Hert op 77-jarige leeftijd. Gertjan Willems blikt terug op het leven van de Belgische filmmaker, chroniqueur en promotor van de (Belgische) filmgeschiedenis: “De jonge De Hert verslond alles wat hij te zien kon krijgen, zonder onderscheid. Als de beelden maar bewogen. (...) De Herts veelzijdige filmconsumptie vertaalde zich ook in zijn eigen filmproductie. Van experimentele kortfilms tot maatschappijkritische filmpamfletten, van metafilm tot populaire komedie, van autobiografische drama’s tot een oorlogsfilm over het verzet, en van de adaptatie van een historische plattelandsroman tot een Elsschotverfilming: De Hert deed het allemaal.”