Doors Closed, the World in View

Into the Classroom and the Cinema with Dirk Lauwaert

Film School Time. Back and Forth Between the Cinema and the Classroom

Herman Asselberghs is currently working on a long-term film project at the film department of LUCA School of Arts in Brussels, where he has been teaching for two decades. Through the realization of a film essay, he probes the relationship between attention and distraction in the film theatre and the classroom. Throughout the creation process, Sabzian reports on his accompanying reading and writing. On a regular basis, Asselberghs selects an existing text that interests him and that he himself provides with an accompanying text. In this second instalment, he probes possible overlaps between teaching and film-watching by means of Berichten uit een klas [Reports from a Classroom], Objectieve Melancholie [Objective Melancholy] and other key essays by the Belgian critic Dirk Lauwaert. He also reminisces about Lauwaert’s overlooked Filmparties.

1.

If a student happens to doze off in my class, I just let them sleep. Good for them. The small auditorium of my film studies class may be one of the rare moments they are offline. A long-term experiment of mine is that, for the last two academic years, I have no longer allowed the use of laptops, tablets and smartphones in my classroom. When the weekly class begins, all devices are switched off. I have to explain this strict rule twice: some students think I’m joking (I’m not), others simply can’t seem to compute this unworldly piece of information. Even though I take the soft approach. I have been told that a famous choreographer on the other side of Brussels presents the students in her school with a plastic bag for them to temporarily dump their cell phones in upon entering the classroom.

My old-school approach certainly has its limitations. As someone who is barely able to decipher his own handwriting, I find it hard to deny students their digital notes. And when memory fails me once again or my knowledge simply falls short, I am more than happy to let the students check the much-needed names, years and concepts online and share them with the whole class. Plus, when an emergency arises in the school corridors, at home, in the streets, or in the world, we will be the last to know for 120 minutes, until the break halfway through the long session. Two times two hours with no outgoing signal. Two times two hours with no incoming messages. Doors closed. We sit down and sit still. The matter at hand is the only thing of importance now. Not unlike watching a film in the cinema in the old days. With the difference that talking is allowed. Very much so, even. But in due course: not during the film, always aloud and never all at once.

In Film Studies, the film screening, generally in the first half of the session, does a lot of the actual work. The projection of the film in its entirety, on a big screen, at considerable volume, allows us to pretend that the auditorium is a film theatre. The film shows itself, and my contribution consists of showing that showing. I accompany the screening. I watch it together with the students and share my own watching and listening experience, my knowledge and my feelings afterwards. I stand in front of the screen, in front of the class. I am in between. I point. Situate. Frame. Circle. I suggest watching it in this or that way. Watching and listening again to a fragment this time around. Or two, or three fragments. Certainly not more. We rely on the memory of the film we’ve all just seen in its entirety. It turns out we don’t all remember the same thing, and that we haven’t all seen and heard the same thing. We focus on the form: not what is shown, but how it is shown makes the projection a film and not a book nor a piece of music, or a stage event, a photograph, a drawing, a painting, a game or a video (even though the film may at times resemble all of those things). We hone in on details: a camera movement, a jump cut, a sound, a glance, gesture, voice, light, colour, décor, location, a pattern, a structure. An exercise (including for me, over and over again) in watching together, listening together, talking together. We share the film, the place, the time. For a moment. No outgoing signal. No incoming messages.

Sleeping during the film is allowed in my class. Besides external reasons (perhaps an impetuous or anxious night), I think dozing off is a response to the screening, pure and simple. Some are deeply moved by it. Others are surprised, confused, bored. Annoyed, too. And yet others fall asleep. I’ve no objection to that. I draw the line at leaving the room. Classrooms and film theatres dictate duration. A film simply takes a certain amount of time. A class as well. Time runs: sometimes fast, sometimes slow (also for me). Sitting down, and sitting still, might become sitting it out. Especially on those uncomfortable chairs (I’m glad I can stand). Falling asleep is not only an act of resistance to the film and the class, but also against the institution’s business aesthetic: the auditorium at this art school has the air of a conference room where managers present their umpteenth PowerPoint. “Sleeping is the only way to wake up from the nightmare,” Walter Benjamin once wrote. Leaving the room, on the other hand, is a short circuit. A sign of rejection or indifference (very rarely of a small bladder or a bladder infection). As a spectator in the cinema, these are valuable reasons to chuck it in, I think. But not as a student in a classroom. There’s proof: after the screening, during the reflective part of the class, no one ever leaves the classroom (unannounced) because they can’t hold out any longer. As long as the door is closed – in old-fashioned terms: until the bell rings – we are here to temporarily suspend our opinions and judgments. We find out all on our own what this week’s case in point is about. What’s at stake in this film, in this class. During the projection, as long as the lights are off, we all only wonder where the film will take us. Even if it doesn’t seem to be of any interest to us at first sight. Even if it doesn’t seem to be of any interest to us by the final image. The inadequacy of the room – a half-baked classroom/half-baked film theatre – is perhaps not such a bad thing: in this setting, even the most captivating of films will retain its study-object status during the screening. Film studies does not consist of a film-screening-cum-class. The film is very much part of the lesson. And, whether or not in the dark, leaving the room during class is downright rude.

I can establish and (try to) enforce as many rules as I want to, I will never be able or willing to control the students’ thoughts. Every student has the right to stare out of the window. The auditorium may not have any windows and the digital connection with the outside world may be temporarily cut off, but nothing prevents students (or cinemagoers) from daydreaming, drawing up shopping lists in their minds, forging creative projects or amorous plans, contemplating family, financial, physical or mental problems while I am trying my best, in front of them, to teach. Or while the film does its thing. Just like the film, I’m not trying to prove anything or convince anyone. I don’t want to win souls; I want to win attention. Here and now.

2.

In pedagogue Jan Masschelein’s many beautiful writings, attention is called a state of being present. To him, being attentive means: “... literally being there, being present and being of the world (things, others). Being absent means not being there, or not being involved, and therefore literally not being there yourself.”1 Staying on point, staying on task, is a matter of becoming attentive. “Being attentive is a state that can be brought about,”2 says Masschelein. “School is the time and place where we become attentive to things, or in other words, school draws attention to something. School (what with its teachers, school discipline and architecture) makes it possible for a new generation to become attentive to the world: things speak (to).”3 To be attentive means to be susceptible. To adopt a susceptible and sensitive attitude beyond ingrained habits, beyond immediate results, instantaneous gains or a certain return. Beyond one’s own tried-and-tested perspective, beyond the self. “To be of(f) the world” means both “to be detached from” and “to be part of the world”. Being attentive takes place in the gap between the self and the world, midway between inside and outside of oneself. Becoming attentive takes place in a state of lift, according to Masschelein, in a state of imbalance, of unrest even. He points out that, in French, attention refers to attendre [“to wait”].4 Attention as a suspension of the expectation of an outcome, as a postponement of position. Attention as a form of waiting.

Masschelein’s critical philosophy of education occurs to me as I read and reread Berichten uit een klas [Reports from a Classroom]. This essay by Dirk Lauwaert dates from 1994 and reports on a decade of art-school teaching.5 In nine short pieces and an equally concise introduction – not more than nine compact pages in book form – the author highlights his role, task and place in teaching. From beginning to end, the piece is vintage Lauwaert. Precisely worded, crystal-clear insights alternate with unresolved attempts at nebulous thoughts. The text is brazenly subjective, betraying an erudite frame of reference and theoretical baggage. Verbal arabesques, glissades and pirouettes: thinking proceeds along an elegant choreography with no floor plan to speak of. I try to keep up. The sober numbering of each section brings the concentrated train of thought to a halt for a moment. As if the writer abandons a winding train of thought before he has completed it. Or even before I have completely grasped it. At each new number in the header, I brace myself for yet another démarche in his dancing considerations. After reading the last sentences, I exhale vigorously.

No true reader of Lauwaert’s wide-ranging work can ignore it: his massive intellectual legacy is spread across a handful of (substantial) text collections, a few separate publications, many forgotten periodicals, various catalogues and, since his death in 2013, online versions of some articles.6 One thick book just never happened. No commentator will fail to notice: both in his disordered oeuvre and in (almost) every single piece of text, systematics loses out to chronicling. A seasoned reviewer of films, books and exhibitions, Lauwaert is a master of reporting. He proceeds from one piece to the next (like a cinephile from one film to the next, I guess) and, in each case, knows how to squeeze his impressions and insights into the prescribed lengths and formats. His more comprehensive texts, in which he affords himself detours and shortcuts, also bear evidence of a high turnover.7 The next sentence, the next paragraph, the next idea (like the next image in a film) rarely takes long. The writing, however, is never a rushed job or an incitement to cursory reading. Velocity is a sign of vitality here.

It was no different when he was teaching, I recall. Once Dirk’s animated train of thought had left the station, you were in for an intense ride. A crash course in the “theory of the concrete” that resonated for hours.8

A notorious film lover, connoisseur and critic, Lauwaert regards teaching as a spectacle with clearly divided roles. The teacher shows something; the student watches it. The teacher presents: “Actually, his only concern when teaching is to make something exist: a photograph, a film sequence, a style, a thought, a way of questioning things, the power with which an idea is advanced in a text, an image, a sequence of images. For this, he would like to use the word beschouwen [“to consider”], which implies the sensory zien [“to see”] but especially the mental schouwen [“to examine”]: to verify. To watch and consider if and how something is.”9 In this class, which he leaves unnamed throughout his text, examination is not only part of a student’s final evaluation. It is the permanent task of a teacher who tests, for example, in each class “if and how” things can be made visible and fully present. Visible means both perceptible and understandable, public and irrefutable.

I vividly remember a semiotics class in which Dirk, by means of a single film clip on VHS and a shabby TV set, managed to explain to me the finesse, complexity, and indisputable relevance of dance couple Astaire-Rogers once and for all. By means of demonstration. He indicated: that is how bodies and camera move together in space and time. To the heavenly strains of Irving Berlin.

3.

In Reports from a Classroom, teaching becomes dosing. The teacher’s task is to find the appropriate speech. He tries to subtly balance presence with the right words and the right silences. “With words he tries to dampen the deafening noise of the silent presence of an image. Speaking, he enchants it, welcomes it, gives it a place so that it can attach itself, leave traces.”10 Elsewhere, in one of his quintessential texts, Hedendaags sofisme en de arme ervaring [Contemporary Sophistry and the Poor Experience] from 1996, Lauwaert specifies his speaking: “Reflection that does not first neutralize experience to never return, but is as close to it as possible. [...] At the end of the day, this means that you don’t solidify the piece into a document – but try to capture its moment and form of appearance.”11 When it comes to teaching or writing, for Lauwaert, reflection can and must never coagulate. Momentary coagulation of thought is inevitable when it is cast in text. But even then, mental agility remains a goal rather than a means for this author.12 One of his collections is called Onrust [Restlessness] for good reason, since movement also includes agitation.

To be moved by movement: it is beyond doubt for me that the intensity of the film experience provides the fertile soil to Lauwaert’s small philosophy of teaching. Film-watching means surrendering to the drift of image and sound, to “naked presence and duration”. These are the terms used by Masschelein to talk about the gradual discovery of a film during the screening: “First there is naked presence and duration. Only then can we assign the fragments a place in the course of events.”13 By definition, teaching and writing about film-watching happens after the fact. The report on the experience of the film always comes afterwards (possibly on the basis of notes made while watching). Like no other, Lauwaert deeply penetrates the tension between experience and articulation. How to reconcile the two? He knows it’s impossible. “Experience is fundamentally stubborn towards words, towards commentary. Especially towards methodical, organized commentary, which straitjackets (or has to straitjacket) the case in point into its starting point. Experience blows language to bits, seduces thinking to go beyond itself, on different paths simultaneously, contradictory and paradoxical. Hence another linguistic strategy, that of a criticism that is always a form of poetry: didactic poetry, didactic poems. Not the expression of emotions or events, but the struggle to see and to know as close as possible to experience.”14 Articulation, in the classroom and on paper, leans against experience but does not ever coincide with it. The gap between experience and reflection is where teachers, critics and essayists operate. Always in the moment, but after the facts. Afterwards, Lauwaert says, the words “only belong to the work as a bowl belongs to the fruit, the pedestal under the sculpture, the wooden frame around the photograph: as a means of attracting attention and expressing appreciation.”15

Teaching is a matter of placement. The teacher is standing next to the work and in front of the class. Those who teach about film also place themselves in front of the screen after the projection (after the screening, the projector’s beam of light regularly hits me in the eye). Contemplating, reflecting, pondering all require distance. From a distance, something can be pointed out or held against the light (so that what’s familiar can become strange). But the bridging of distance is just as necessary (so that what’s strange can become familiar), for “in order to make something comprehensible, you have to make it graspable”, Lauwaert knows. “Grasping begins with tangibility. Around the work has to be constructed an immediacy [...].”16 According to him, to teach is “to get to know”: to present to each other like a host, to bring together, to offer a shared subject. For the work is old and comes from afar, the pupil is young and not well travelled: both have to get into each other’s presence.”17 Masschelein and his pedagogue-comrade Maarten Simons put it this way: in school something is “put on the table”, and what matters is “staying on point, staying busy with or present at something”.18 Creating a shared ground between teacher, pupil and the work is a matter of finding the right relationship between distance and proximity. In the film theatre, Lauwaert shows himself to be a master of this balancing act. In the classroom, however, he seems to emphasize the gap between teacher and pupil. In his view, learning “has to do with demonstration and example. That presupposes a radical break between those who demonstrate and those who look on.”19 For him, the classroom situation presents itself as a problem based on a misunderstanding. Teaching is a “vaudeville: a farce in which the blindfolded teacher is chasing dozens of ruthless students”.20

Indeed, what I remember of Dirk’s lessons in semiotics is his (inspired and inspiring) soliloquy, as if it were an (exciting) show, a (compelling) spectacle of thinking in motion. His thoughts took shape out loud, right there in front of me, with little room for dialogue or dissent. That was just his nature, he seems to suggest in Reports from a Classroom: “At least, that’s what happens in my case: I like to take a seat and listen to people for whom something already exists in thought-out form.”21 The fragile relationship between distance and proximity that is analyzed in Reports from a Classroom is mainly that between teacher and work. The equally brittle relationship between teacher and pupil is unambiguously seen from the perspective of teaching: in Lauwaert’s class, the student is a witness in the second row.

Yet distance is not the same as detachment. In his later reflections on cinema, Lauwaert makes a clear, qualitative distinction between passionate moviegoers and detached consumers. The difference between the two is a matter of (dis)belief. The one deems film “not only an instrument of distance, but also a wonderful way of being with the world”,22 “albeit in a roundabout way that is at once a revelation: a revelatory distance”.23 The other is the product of “an ideal critical education with regard to images” and approaches film images “with suspicion, even hostility, and disdain”.24 The difference between the two lies in the importance that Lauwaert, throughout his work, attributes to experience. In Reports from a Classroom, I come across what might be his loftiest definition of the core concept: “The most important thing falls outside the realm of learning and teaching, namely experience: that which is drastically and variably directed only at you. The appeal is unique, once-only, unplannable: ultimately of the order of epiphany, of ‘grace’, of the undeserved ‘gift’.”25 Those winged words count as an article of faith. In fact – surprisingly enough in an article on pedagogy – they subordinate pedagogy to revelation. The experience of the classroom is very similar to the situation of the film theatre that Lauwaert elsewhere refers to as “essential, sublime distance”.26 Between the lines, teaching and film-watching turn out to operate using the same curious formula: proximity through distance.

4.

What is the respectable teacher/respected film critic looking for in an adult movie theatre? An experience, that much becomes clear in Objective Melancholy, undeniably an (early) key text in Lauwaert’s collected work as well, and very much worth our while dwelling on as an unsuspected counterpart of Reports from a Classroom.27 The piece is from 1982, when sex films still ran in specialized cinemas where the author occasionally ended up. Even though he does not at all wish to legitimize his visits, he provides us with enough grounds to appreciate “this cinema, the pornographic one” as well. The true significance of this particular excursion gets confirmed in yet another text by his hand, one of his most important essays from more than a decade later. In Dromen van een expeditie [Dreaming of an Expedition] from 1995, the author takes stock of the profound change that film and his film-viewing have undergone since the early 1970s. It’s his own personal account of loss, a retrospective of a time lost forever, in which film was “a different, radically innocent, free-floating culture”, “without institutions, without an official language, without norms”.28 Objective Melancholy celebrates pornographic films not only as an integral part of cinema, but above all as the vanguard of the gloriously “uncontrolled territory” that cinema appeared to be able to occupy for him at the time.

In the hands of Lauwaert, sex films form a real film-watching training. The genre strikes him as the real thing. Just as the simple registration of movement (of a train, a child, or the leaves on a tree) in the silent shorts by the Lumière brothers blew the minds of their very first spectators, so the disarming flair of these rudimentary feature films drives him to pure amazement. He admires their simplicity, carelessness, and brutality. Here, undevelopedness ensures vitality. A lively screening for an enthusiastic spectator: “Being a spectator in an adult movie theatre: tiptoeing, tingling with acute self-awareness.”29 The spectator is confronted with the ingrained ideas and habits of both decent film culture and his own, practised gaze. “That good cinema has become familiar to me, all too familiar,”30 Lauwaert notes while enjoying the indecency of the entire affair, “without any redeeming quality”.31

But, once a critic, always a critic? He may have slyly cocked a snook at the institutionalized (film) culture of the time, but his naughty piece reads like a textbook example of thorough, non-academic film analysis. Without mentioning any title, any category or subcategory, any maker or actor, without mentioning what is actually to be seen on the screen, Lauwaert meticulously analyzes the mise-en-scène of this scandalous but nevertheless fully-fledged (and popular) genre. The position and juxtaposition of bodies, props and accessories in the décor, the acrobatics of bodies unabashedly showing themselves in full glory and action, the actors’ request for a frank and immediate response of the spectator to their continuous faking of pleasure and persistent climactic postponement: as usual, not a single detail in the cinematographic design escapes the attention of the experienced reviewer-cum-essayist. Initially, I did not sense any systematics in his findings. In the second (and third) reading, it becomes clear to me how his free-rein thinking leaves few facets of the subject unexplored. And the subject is: pornographic film as seen from the experience expert’s cinema seat.

Objective Melancholy is, unintentionally, a bit of a droll piece. Who seriously wonders, in a reflection on pornographic film, whether people still read (Sontag, Vidal or De Beauvoir)? Never before have I read a piece about pornography in which the issue is approached with so much pudency. The author does not fail to interpret his self-chosen modesty. Commenting on the directness of sex films in outspoken terms would mostly serve the usual “rejection and looking away”. “If you want to talk about porn (and not about disgust and fear), you have to choose your words carefully and prudishly.”32 With his deliberate choice for the secret paths of the bon mot, Lauwaert manages to reveal the characteristics of the film genre and, in passing, his own position. Apart from one or two or three shrouded allusions to his own masturbation activities (a redeeming quality, after all?),33 the expert by experience unmistakably shows himself to be an eternal spectator and not a regular user. When he proclaims his aversion to erotic cinema (the so-called “better” porn film), I find him hard to believe. This bold statement seems to me to be serving a mostly provocatory purpose, while his suggestive style of writing precisely argues for veiled instead of perky nudity (he is the man who describes critical reflection as “the touch of the hesitant lover”).34 Later, in his sensitive studies of dressed bodies and cut fabrics in fashion, he quite unsurprisingly went exactly the opposite way.35 There is a limit to every elegy of “the vitality, the festivity, the triumph of the physicality”36 of porn. A sex-positive appreciation of the genre is an appropriate answer to the objections of bigots and hypocrites, but it is indeed based on gender-friendly image representations and emancipating film practices, not on the abstract, absolute category of “porn” that Lauwaert likes to use.

The blind spot in Objective Melancholy surprises me. How can this experienced spectator ever have descried carefree liveliness in the porno chic films that, by his own account, led him to the “real thing” by way of mainstream cinema in the early 1970s, particularly Last Tango in Paris and Deep Throat? How could he ever descry “inciting liveliness” in these notorious successes, based on male fantasies of chastening anal sex (for him, by him) and orgasmic blowjobs (as the clitoris is conveniently located in her throat) respectively? And “unquenchable cheer, a contagious self-irony that does not create distance, but adds intellectual complicity to the eroticism”?37 Does the “unadulterated stuff” he takes in in shady cinemas have those same “qualities”? Because in both of these famous feature films I mainly see laughable machismo/nasty misogyny at work, and I wonder whether Lauwaert, also in his memories, didn’t get carried away by the far-out and indeed lively seventies soundtracks of both films. For those who, like him, regard filmmaking as “the realm of the father”,38 cinema as an essentially “male mechanism”,39 film-watching as “a magic garden for orphaned sons entangled in Oedipal impasses”40 and pedagogy as “the continuation of paternal (parental) relationships”,41 it is of course difficult to shove aside their patriarchal views when consuming (implicitly and obviously heterosexual) porn. Gender blindness is a constant throughout Lauwaert’s essay (and his entire work, I dare say). Objective Melancholy’s publication date is hardly an excuse: the convincing stories of the on-set abuse of actresses Maria Schneider (in Last Tango) and Linda Lovelace (in Deep Throat) may have emerged post factum, but the anti-pornography movement of the second feminist wave had been airing its criticism since the mid-1970s and explicitly made Deep Throat a legal case study. One viewing experience is clearly not the other.

“Experience”, once again, the magic word in the Lauwaert catalogue. And what may have started to seem like a long detour in my own writing, nevertheless leads directly to the heart of his view of teaching. From the classroom to the porn theatre (as the purest blueprint of the cinema) and back. Beyond provocation and in addition to gender indifference (and dormant sexist thought), the teacher-spectator in Objective Melancholy exposes what it is always about for him: to provide the student and the reader with “a look into the eyes of the work” with a view to “creating the possibility of a ‘first look’ that unleashes infatuation”.42 Always on the look-out for the intensity of that original encounter. Hence, no doubt, his many beautiful and heartfelt paragraphs and whole pages in his writings devoted to his own childhood, to silent film, to nineteenth-century sensibilities in the arts (in many respects, the century that gave rise to the twentieth century, and of course the origin of cinema). Hence also his growing cultural pessimism, his rising (intelligent) lamentation over just about anything of topical interest at the end of the last and the beginning of this century – contemporary art, the academization of higher art education, contemporary cinema, television, information, current affairs. From that point of view, or rather, in that state of mind, experience as such is bound to be liable to demise as well, individually fading into memory or collectively replaced by experiences, by kicks.

When Lauwaert, in Dreaming of an Expedition (1995), says goodbye to his great love of film, the inevitable break was already dawning in Objective Melancholy thirteen years earlier. In the porn theatre, he finds himself furthest removed from the institutional frameworks that stand in the way of any original (film) experience: museums and academia. Respectively, the institution that “offers ready-made and too many answers without listening to the questions” and the institution saying that “film and film-watching are not the core, but that we are in front of objects we analyze according to a method to be verified, all too often at the expense of the film and film experience itself”.43 The porn theatre is the ideal anti-institution. Pornographic films provide proof of what has to be said over and over again, “that the film experience is crucial, that it is physical-erotic. It has to be repeated that the support is neither celluloid nor magnetic tape, but the social experience as such.”44 The porn viewer – this porn viewer, i.e., the experienced film critic Dirk Lauwaert at the beginning of the 1980s – reports about a new “first look”, about a “descent into the unknowably other”, as he aptly formulates teaching in Reports from a Classroom. Face to face with a sex film in a porn cinema, this teacher-essayist is rather like the students he thinks of, who open their minds to “that which is drastically and variably directed only at you”. In Objective Melancholy, the porn genre appears as virgin territory worthy of the expedition, as long as there is a chance of experiencing revelation.

5.

Experience, once again. It begins to dawn upon me how Lauwaert uses and promotes this concept. He is not interested in the experience that wears off, that constantly searches for new impulses, that eagerly looks forward to the next time. He is interested in the experience that matures, that is embedded and builds on previous times by way of tradition and transmission. Some readers have the impression that his texts have no educational ambitions.45 It is true that they rarely want to explain or educate. Still, I cannot but hear a teacher speaking who wants to transmit and relate the thinking of experience to the experience of thinking.

Lauwaert’s critical philosophy of education comes to mind as I read and reread Denken/aandacht [Thinking/Attention]. In this text, Jan Masschelein describes thinking as movement without direction, without purpose. Thinking is not a straight line to knowing or knowledge. It is movement in all directions, driven by curiosity. Moving in thought is literally a movement as well, a moving body.46 The mise-en-scène of thought displays postures, gestures and facial expressions in a state of restlessness, “of being without a place or not having a place, of constantly searching for one’s place”.47 Wasn’t Benjamin the one who, as described by his friend Scholem, apparently couldn’t sit still while exchanging ideas? He paced through the room while forming his sentences, at a certain point stopping to give his opinion on the matter in an intense voice.48 I read Lauwaert’s essays as a mise-en-page of a similarly agile thinking that, in the words of Masschelein, appears as an “activity that takes places in a state of ‘suspension’”.49 He uses essays, again in the words of Masschelein, as a mental exercise, as an attempt “to clarify certain issues and gain a kind of certainty with regard to specific questions. They are attempts to breathe new meaning into words, to inspire.”50 Such mental exercises are outspokenly educational to the pedagogue. If only because the essay displays its own mental process in its “searching” style. But above all because it performs a public gesture “inviting others to share the experience and form an audience”.51

Masschelein recognizes the essay form not only in texts or in lectures, but also in film, especially in the work of the Dardenne brothers. To him, their films offer “a kind of ‘seeing for the first time’ which sets thought in motion”.52 Thought that not only leads to insight but also to an experience “that is also an experience of freedom”.53 This description of the experience of thinking in terms of possibility is very close to Lauwaert’s pedagogical lament in Reports from a Classroom: “It is necessary to work on the restoration of the ability to gain experience, of the awareness that in the end things don’t have to (be available), but can (be possible).”54 Both authors share their view on the need for a learning environment in which efficiency and functionality lose out to the potential of the playroom and waiting room. It is Masschelein who explicitly relates the classroom situation to a film screening in terms of indeterminateness. When watching films, we “sit and wait, without knowing what we are waiting for, and that is precisely what makes us stay with the film in a way”.55 “In the classroom, students can be drawn into the present, freed from the possible burden of their pasts and the possible pressure of a mapped-out (or already lost) destiny. [...] School should rather be considered a kind of pure medium or middle. School is a means without a purpose or fixed destiny.”56

Masschelein describes the film experience as a pure form of perception in which expectations are suspended and judgments postponed. He argues for film-watching “without immediately wondering whether it is useful, whether there is something to gain, whether one can learn something from it”.57 This approach to film-watching as the adjournment of a functional search for explanation and elucidation is in keeping with his apology of school as a place for learning without immediate finality, as an open-ended activity, as indefinable time. In his plea for a school that aims to offer a productive, free space-time for the long, formative waiting for a new destiny, for an after-school future, I recognize Lauwaert’s relentless defence of the primacy of experience. In 1996 he notes: “Today, young students look at photographs and their ‘impact’, at films and how ‘efficient’ they are; art lovers look at art and how ‘interesting’ it is. ‘Interesting’ is the death of the experience. [...] An interesting experience cannot yield ‘interest’. An experience is not functional, but compelling, disruptive, exhausting, extreme.”58

6.

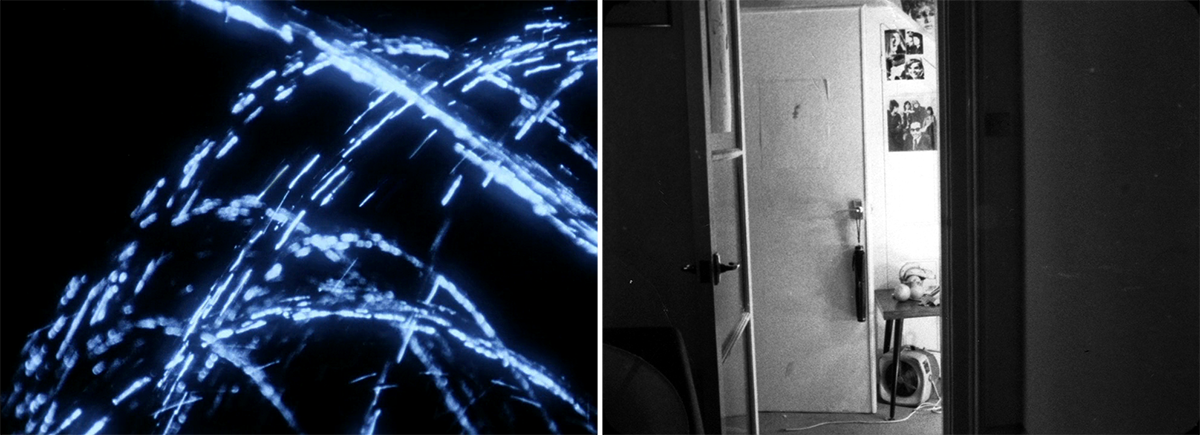

For three consecutive years in the first half of the 1980s, Lauwaert organizes a unique film programme for the Leuven arts centre Stuc (still with a “c” then – now with a “k”, STUK – and not yet institutionalized), which is somewhat misleadingly titled “Filmparty”. A dance floor is nowhere to be seen. It certainly is a feast for the eye. From noon until well into the night, the audience is treated to a marathon screening of experimental films. Some of the titles have by now officially become part of film history, but anyone in Belgium in the early 1980s who wants to see works by Warhol, Genet, Kubelka or Gidal has to go abroad or occasionally turn to the Brussels Film Museum, De Andere Film, or other scarce initiatives on the fringes of the established film scene.59 The first Filmparty (25 March 1982, from 12:30pm to 3am)60 boasts no less than twenty titles, following each other in two long blocks, with only a one-hour meal break (at 7:30pm).61 A ticket of 250 Belgian francs or 180 BEF with a student card (approx. 6.20 or 4.46 euros today) is worth Dwoskin’s Alone, Gidal’s Hall, Akerman’s Saute ma ville, Mekas’s Reminiscences of A Journey to Lithuania, SLON’s L’usine Wonder, Markopoulos’s Ming Green, Warhol’s Couch, and Genet’s Song of Love, among others. At half past one at night, Schroeter’s Eika Kattapa closes the night. It is a complete immersion in much talked-about but seldom seen films of diverse origins, lengths, styles, forms and sensibilities. In the noisy auditorium, one sits on platforms with cushions lying around for those who are able to get hold of them. Dedication and perseverance are part of the happening. Despite the lack of any cinema comfort, the 16mm projections are clearly enchanting. The next year (18 and 19 February 1983, from 2pm to 4.30am) and the year after that (25 February 1984, from 2pm to 4am) Stuc sticks to the same formula. Among other things, Filmparty Two offers Anger’s Eaux d’artifices, Snow’s Wavelength, Costard’s Der kleine Godard an das Kuratorium junger deutscher Film, Von Pauheim’s Berliner Bettwurst and again features (other) titles by Warhol, Dwoskin, Mekas and Kubelka and Song of Love. The compiler notches it up: with sixteen titles in two blocks, the programme has fewer but longer films; the only break (not until 9pm) lasts only half an hour; and at around half past two, Schroeter’s The Death of Maria Malibran is the last film to start. Filmparty Three brings Dwoskin’s Trixie, Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer, Michael Snow’s <-->, Lowder’s Parcelle, and again Song of Love. The last edition is a hardcore one: no less than twenty-six titles in again two blocks, but without a break this time. In the evening, there is Mekas’s Walden; Warhol’s Chelsea Girls starts after midnight. Afterwards, Schroeter’s Neurasia plays the night out.

In my memory, three Filmparties blur into one impression, into one (charged) atmosphere, one intensity. I’m not even sure if I attended the first instalment. I think I did. I definitely remember films (some of which I didn’t get at all) and parts of films. Specific images and entire sequences etched in my memory. Voices and sounds to never forget. During the projections there was a constant, muffled coming and going (much like in a porn cinema). At all times of the day or night, spectators snuck in, out and back in. Some undoubtedly left for good. I was in it for the long haul.

In Dreaming of an Expedition, a selection of Lauwaert’s collected thirty years worth of writings on film, experimental film is remarkably absent. Apart from his ode to pornography, the contents cover a wide range of mainstream cinema culture, the reviewer-essayist broadly interpreting the film-auteur figure (from Minnelli to Kiéslowski, from Spielberg to Akerman, from Godard to Blake Edwards) and stretching it (the actor as an author: Jerry Lewis, Louis de Funès, Fred Astaire, Jean Seberg). Why are experimental filmmakers missing from this list? There is no shortage of interesting material on this topic. There are not many texts, but the few that exist are not less meaningful. Each Filmparty is accompanied by a programme magazine in A3 format: a paper of around twenty pages chock-full of already existing articles, interviews and excerpts from international publications, reproduced in facsimile. Here too, Lauwaert functions first and foremost as the compiler. In each paper he provides a view of the most important filmmakers, authors and magazines in the field at the time. His varied selection in English, French and German give a lively impression of the industrious but hidden film world he terms “underground”. A debatable term. From a film-historical point of view, it covers the titles by Warhol, Anger, Mekas & co, whereas the works of Gidal, Kubelka, Snow, Nekes and others better come under “experimental film”. Only in the third and last paper does the editor pay noticeable attention to terminological questions.62 As it turns out, there was ample choice to name “this kind of” films: avant-garde film, formalistic cinema, experimental film, independent film, marginal film, le mauvais genre, l’acinema. Throughout the three editions, Lauwaert personally swears by “underground movies”. With the recurring motto: “I want to show you different emotions.”

None of the texts in the Filmparties magazines are written by Lauwaert. Except for the three very short forewords in which he does not mention any names of films or filmmakers from the programme, but always tries to articulate the existence of the genre. As announced on the cover, which also served as a poster, the personal perspective is crucial: the film marathons were clearly “a personal choice by Dirk Lauwaert”. The answer to the question of “Why these films?” is therefore unequivocally to be found in the life of the compiler who wants to “repeat ‘where I come from’ to old friends and show it to newer ones. Documents from a biography.”63 In and since the late 1960s, the films had clearly made a deep impression on him, “for something happened between me and these films. I ‘fell’ for them. Unannounced, uninvited, unprepared, with overwhelming immediacy. No negotiations, no compromises, surrender without conditions.”64 The statement in this intro dates from March 1982, Objective Melancholy dates from a month later. No wonder I recognize its ode to the underground film as an ode to pornographic cinema, and vice versa. Both unregulated, at times disruptive, film experiences turn out to provide the same qualities. Paradoxical, dissolute, inappropriate. Experimental film, too, provides a direct “connecting line between eye and body – without the censorship of what is beautiful or ugly, decent or obscene, captivating or boring”.65 This mauvais genre, which does not require any justification either, does not aim to convince, seduce or persuade its audience, “in these films there is only seeing”.66 Films of which Lauwaert only “says they exist (and the best way to say that is to show them). They are there, they were made, they are being watched. That’s not a huge argument in their favour, but it is the first, the essential one.”67 The spectators of underground film embody its overlapping with pornographic film: “These films have forged in me the figure – amoral, unrelenting and vulnerable, melancholic and indifferent – of the spectator, of an absolute gaze.”68 Masschelein’s description of the film experience as a “pure form of perception” becomes more relevant in the context of experimental film than in that of the mainstream cinema of the Dardennes. The spectator, thrown back onto themself, face to face with this other “uncontrolled territory” of unconventional, difficult to categorize film works, becomes aware of their own gaze, for “what is shown does not conceal the watching behind a sophisticated narrative, but shows us the watching as such”.69 I understand and consider it as follows: conscious, committed attention to these eye-opening films that, when projected, with their long, slow, “empty” duration, make bodies as well as the screen, the projection, the room and the spectators tangibly present, keeps us with the “lesson”. It brings us to the point. To ourselves. Beyond ourselves. We become attentive to our own, shared attention. We become aware of our own and someone else’s gaze. We see ourselves watching together.

Despite the similarities qua viewing experience between underground and porn films, there are big differences. Experimental film is close to art and thrives on the identification of its maker’s unique character. Even in structural film, which seeks to shift the film author’s character to the background in order to uncover the material conditions of the film apparatus, there is a world of difference between the worlds of Paul Sharits, Hollis Frampton, Peter Gidal and Peter Kubelka (the first two big names remain surprisingly absent from each Filmparty line-up). Who, on the other hand, apart from a few aficionados, cares about the director’s name or fame in a grimy sex cinema? Or about the film’s title, story and style? While in porn cinema narration and form are secondary to action, they play a leading role in experimental film. The form is free: anything is possible, nothing is compulsory. The standard narrative is non-existent, or at least disrupted or undermined. The spectator can expect a lot. Lauwaert is not blind to the possible consequences of this drastic autonomy. He notes: “...how irritating the consequences are sometimes! How tiring the vitality! Why do they scare so much with their rabid consistency?”70 The genre’s impertinence and tactlessness turns out to be both a plus and minus point, part of playing for high stakes. While nameless porn films seem to dwell in a parallel universe to mainstream film, here the roles are practically reversed: measured against the unusual radicality of underground film, the well-known narrative cinema appears as a completely “other” cinema. This reversal makes even Lauwaert, a passionate advocate of all popular film genres, long for familiar territory, as “the nostalgia for elegant compromise, for care and subtlety is irresistible. In a not so unguarded moment he longs for the ‘other’ cinema, the familiar one, which acquires a surprising loveliness in this company here.”71 While there is definitely a sneaky overlap between the audiences of commercial and pornographic cinema, the crossing from mainstream to experimental territory is less obvious. Traffic in the opposite direction, from underground to overground, happens under a strictly cinephile flag. Lauwaert shows himself to be an experienced commuter. In his bold cheering of pornographic film, he welcomes the gap with the official popular cinema. In his celebration of cinematographic experiment, he similarly confirms the strength of extreme difference, but this time the provocation is to be found in his proclamation of the unexpected affinity between seemingly incompatible worlds. It’s hard to put it any more sharply: “People say that these films are ‘different’ – but they fascinate me because they are still films. [...] I put each of these little works on a par with Disney’s Snow White, with De Milles’s Samson and Delilah. Very often, I see related impulses between these extremes.”72 And still, even more sharply formulated, against both the waylayers and the guardians of these “obscure” films: “The uniqueness of these underground films is that, despite their formal idiosyncrasies, they do not belong in any avant-garde: which guarantees their vitality and our enjoyment. The film apparatus is essentially popular: the film projection presupposes a room, always functions like a spectacle, calls for an audience.”73 According to Lauwaert, film is film; its popularity cannot be measured in terms of the tickets sold for this or that title, in this or that theatre, but it’s at the very heart of its operation.

Lauwaert wouldn’t be Lauwaert if he didn’t personally disenchant the object of his infatuation. At the third and final Filmparty, his defence of underground film rests mainly on counterarguments. He thinks the films in the “strange collection” he has put together are downright narcissistic, rigid and all too serious, devoid of any opening to the viewer, “films in a vacuum; conceived as machines, machines however that produce nothing – no pleasure, no audience, no warmth”.74 I wouldn’t be surprised if, with these words, he wanted to save the genre, the by then notorious marathon event, and his person (as a specialist in the field) from respectable institutionalization. Third time’s the charm, he must have thought. If these films “won’t stick together into a school, a movement, a tradition, a culture”, then there is zero need to bring them together, or to “force them together” into his words. The final foreword’s final paragraph looks back with a note of pity even before everything is over: “Films like ruins; battered, crumbled, fragmentary, mutilated. A carcass that will never be completed.” In the last lines, the sad remnant of a start to little or nothing turns out to offer the ultimate satisfaction: “Unfinished but therefore extra fascinating. There were times when they had ruins designed and built – made to measure. That’s the emotional family the careful enthusiasts of these films belong to.”75

“Feelings for ruins” sounds like a nice summary to me of both the whole Filmparty project and the entire expedition to the porn theatre. In the first half of the 1980s, both of Lauwaert’s anti-institutional undertakings sound almost anachronistic from the outset. It’s the pivotal period in which experimental celluloid film practices are chased by the advent of video art and the porn industry exchanges the analogue film camera and projector for video technology. Lauwaert both leads the way with his keen focus on “other film” and finds himself in the wake of history. This ideal position enables him to make something present at the moment of its disappearance. To make something exist fiercely, without the risk of coagulation.

7.

Soon, my film studies class will resume. It’ll be including face masks and a one-and-a-half-metre distance between those present, with half of the students online elsewhere. More than ever, I wonder how to realize film screenings and classroom dialogues in the school institution. How, for a moment, to turn the auditorium into a classroom and cinema worthy of the name. A fleeting, shared place of exchange. A temporary household of shared attention. The uncomfortable chairs and soulless interior are now luxury problems. As soon as the state of exception can be lifted, the next problem will reveal itself. How do I talk to young people today about the classroom, pornographic film and experimental film as seen and experienced by Dirk Lauwaert? In his reports of (soon) thirty or forty years ago, the end of the last century seems a lot further away than in those by Serge Daney, Roland Barthes or Susan Sontag (to name but three authors he had a strong affinity with).

On occasion, I still serve my students the Astaire-Rogers footage. I point out the elegant turning of Rogers’s dress, which embodies graceful lightness in spite of its heavy hem. I draw their attention to the effortless performance of the romantic couple’s virtuoso dances, which were nevertheless conceived and rehearsed in duo by Astaire and his regular male co-choreographer. I direct their gaze to the precise camerawork that Astaire never allowed to fragment the dancing bodies and to cut the real duration of their performance as little as possible. I first learned these and other details from Dirk and then discovered them in Arlene Croce’s wonderful book which he recommended to me.76 But, unlike Dirk, I also point out the escapism of Hollywood musicals during the Great Depression, the particular character of American film presenting itself as a universal model, the similarities between Fordism and the Hollywood factory, the glorification of romantic love under a heteronormative flag, the blind ode to modernity. Enchantment and disenchantment go hand in hand, I believe. The natural sacrosanctity of film classics is a myth. I see it on my students’ faces. Big-eyed, they watch a Hollywood film from wellnigh 100 years ago. Dirk was five when the Astaire-Rogers duo made their last film musical in the late 1940s. I was six when Astaire finally retired from dancing at the end of the 1960s. By then, Rogers’s film career was already over. As a teenager, my father saw their glorious film series in the cinema. Even before he had to go to the front in the Second World War. Today, many wars later, the Astaire-Rogers musical appears to be a less than urgent message from a distant past for those young twenty-somethings in my class.

Today, temperatures are rising. Forests are on fire. Ice caps are melting. The UK has split from the European continent. The US remains on the verge of civil war. Migrants are in camps. Boats are sinking. A virus has paralyzed the world. Two decades into the twentieth century, today feels like an endgame. To some. To others, this is an exciting time of radical change. A time for action. The self-evidence and achievements of the old world are slowly but surely making way for new ideas, movements, achievements. My students want to speak and hear about decolonization, anti-racism, sexism, abuses of power and the ecological state of emergency. Not least because the white, neo-liberal school institution is lagging behind considerably when it comes to addressing pressing worldly issues.

And yet, the classroom and the cinema function optimally with doors closed. Teaching, taking class, and film-watching are all based on the same cunning deal, on a paradoxical artifice: we keep the world out so that we can let it in. With cinema doors closed: in the midst of the world, briefly out of its sight. With doors closed in the classroom: in the heart of the institution, off its grid for a while. How annoying those glass doors of “modern” classrooms are, with every passer-by reminding me every other minute of the drag of daily life by heading straight and hastily for their destinations. How irritating, at times, the latecomer in the cinema is who stands between me and the screen, or shuffles behind my back in the dark, looking for and ultimately finding an empty seat. How sobering for teachers, students and spectators the glowing screen of a smartphone is, with its soft flash making a trifling message from the outside world seem important.

In today’s rapidly changing digital living and working environment, the classroom and cinema are liable to fundamental transformation. The self-evident nature of plugging into the online network provides us with a radically different interpretation of “being in class” and “going to the movies”. Due to all kinds of distance learning and virtual learning environments, the multiplication of screens and online access to films and tutorials, physical movement and presence are no longer necessary. Every viewer is by definition a user: intervening in the flow of the moving image and touching the screen are rule rather than exception. The interruption that really interrupts always surprises; but it has become obvious today and rarely surprises us anymore. Texts, Facebook, Insta or TikTok might interfere at any time. Especially when the film screening or class takes place at home via the intimate workstation/communication centre of our laptops or desktops. But equally so in the film theatre and classroom. The ping of an incoming message and the flashing on of a mobile-phone screen have become familiar attention-curve interruptions to teachers, students and cinemagoers, making it hard to stay with the class or the film. The school’s and the cinema’s capacity of opening up the world, of arousing interest by establishing a state of committed attention, is considerably put to the test when the everyday, functional world cannot even be kept at a distance for a while, when this here message asks to be read and answered right away. My own phone, too, happens to light up or even ring while I am in front of the class or sitting in the theatre. How annoying, disturbing and sobering. But I find this actual interruption less intrusive than my deep-rooted sense that interruption lies dormant, might happen at any time. And that it won’t startle me. Better to wait then, rather than to expect (something or other). With no outgoing signal. With no incoming messages. For just a moment.

- 1J. Masschelein, “Denken/aandacht”, in: J. Masschelein (ed.), De lichtheid van het opvoeden, (Leuven: Uitgeverij LannooCampus, 2008), 39-53. Quote: 50.

- 2J. Masschelein & M. Simons, Apologie van de school. Een publieke zaak, (Leuven: Uitgeverij Acco, 2012), 52.

- 3Ibidem, 34.

- 4Masschelein, “Denken/aandacht”, 51.

- 5D. Lauwaert, “Berichten uit een klas”, in: Artikels, (Brussels: Yves Gevaert Uitgever, 1996), 34-43. For a chronology of Lauwaert’s teaching trajectory, see: B. Meuleman, “Kroniek van een afgeladen leven, na de val uit het paradijs”, in: De Witte Raaf, 191 (January-February 2018), 7-9.

- 6Over the course of almost five decades, Dirk Lauwaert (1944-2013) regularly published on film, fashion, photography, the city and the visual arts in Flemish and Dutch cultural magazines such as Film & Televisie, Kunst en Cultuur, Versus, Skrien, Andere Sinema and De Witte Raaf. Artikels (1996) was a first collection of his texts. Three more were to follow: Dromen van een expeditie (2006), Onrust (2011) and De geknipte stof (2013). On the occasion of the first and fifth anniversary of his death, De Witte Raaf took a step towards unlocking Lauwaert’s literary legacy – see the extensive documents devoted to his life and work, accompanied by previously unpublished texts, in De Witte Raaf, 171, 191, 192 and 193. In the past five years, Sabzian has contributed to Lauwaert’s introduction to the English-speaking world, see sabzian.be for a growing collection of translations.

- 7Rudi Laermans characterizes Lauwaert as “a short-distance runner: he ‘gasps’ from one paragraph to the next, if not from one sentence to the next.” R. Laermans, “Dirk Lauwaert als criticus. Fragmenten voor een intellectuele biografie”, in: De Witte Raaf, 192 (March-April 2018), 2-5. Quote: 2.

- 8Lauwaert, “Hedendaags sofisme en de arme ervaring”, in: Artikels, 207-219. Quote: 208.

- 9Lauwaert, “Berichten uit een klas”, 41.

- 10Ibidem, 42.

- 11Lauwaert, “Hedendaags sofisme en de arme ervaring”, 208.

- 12“Lauwaert is a pre-eminently agile writer-thinker who seems to be almost terrified of his ideas coagulating into well-rounded insights.” Laermans, “Dirk Lauwaert als criticus”, 3.

- 13Masschelein, “De cinema van de Dardennes als publieke denkoefening. In de bres tussen verleden en toekomst”, in: Oikos, 55 (April 2010), 38-46. Quote: 38.

- 14Lauwaert, “Hedendaags sofisme en de arme ervaring”, 216-217.

- 15bidem, 209.

- 16Ibidem.

- 17Ibidem.

- 18Masschelein & Simons, Apologie van de school, 28.

- 19Lauwaert, “Berichten uit een klas”, 36.

- 20Ibidem, 35.

- 21Ibidem.

- 22Lauwaert, “Dromen van een expeditie”, in: Dromen van een expeditie. Geschriften over film, 1971-2001, (Nijmegen: Uitgeverij Vantilt, 2006), 111-116. Quote: 115.

- 23Ibidem, 114.

- 24Ibidem, 115.

- 25auwaert, “Berichten uit een klas”, 39.

- 26Lauwaert, “Dromen van een expeditie”, 112.

- 27Lauwaert, “Objectieve melancholie”, in: Dromen van een expeditie. Geschriften over film, 1971-2001, (Nijmegen: Uitgeverij Vantilt, 2006), 49-45.

- 28Lauwaert, “Dromen van een expeditie”, 113.

- 29Lauwaert, “Objectieve melancholie”, 49.

- 30Ibidem.

- 31Ibidem.

- 32Ibidem, 30.

- 33Ibidem, 50.

- 34Lauwaert, “Hedendaags sofisme en de arme ervaring”, 209.

- 35Twenty years after Objective melancholy, Lauwaert ascribes more potential to the veiled than to the naked body: “Man does not seem to be naked existence. Only as a textile body does he become himself, only when dressed can the human adventure begin. Undressed, there is a lack of existence. Undressed, one is disformed, deformed. [...] Only in clothing does one free oneself from the species and respond to the species as an individual. The joy of being dressed is an expression of the essential liberation of mankind.” D. Lauwaert, “Intimiteiten uit de garderobe”, in: De geknipte stof, Schrijven over mode, (Tielt: Uitgeverij Lannoo, 2013), 135-161. Quote: 141.

- 36Lauwaert, “Objectieve melancholie”, 54.

- 37Ibidem.

- 38Lauwaert, “Dromen van een expeditie”, 114.

- 39J. Reyniers & C. Van De Velde, “Het feminisme heeft het vrouwelijke in de film vernietigd. Dirk Lauwaert over cinema”, in: Veto 15, no. 22 (6 March 1989), 7.

- 40Lauwaert, “Dromen van een expeditie”, 114.

- 41Lauwaert, “Berichten uit een klas”, 35.

- 42Lauwaert, “Hedendaags sofisme en de arme ervaring”, 209.

- 43Lauwaert, “Dromen van een expeditie”, 116.

- 44Ibidem.

- 45“After all, his work did not serve any educational or social purpose.” B. Verschaffel, “Verliezen met stijl. Lezen en schrijven volgens Dirk Lauwaert”, in: De Witte Raaf, 193 (May-June 2018), 9-10. Quote: 9.

- 46Masschelein, “Denken/aandacht”, 47.

- 47Ibidem, 40.

- 48G. Scholem, Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship, (New York: The New York Review of Books, 2003), 12-13.

- 49Masschelein, “Denken/aandacht”, 39.

- 50Ibidem, 38.

- 51Ibidem.

- 52Ibidem, 44.

- 53Ibidem.

- 54Lauwaert, “Berichten uit een klas”, 39.

- 55Masschelein, “Denken/aandacht”, 51.

- 56Masschelein & Simons, Apologie van de school, 25.

- 57J. Masschelein, “Inleiding”, in: De lichtheid van het opvoeden, J. Masschelein (ed.), (Leuven: Uitgeverij LannooCampus, 2008), 9-18. Quote: 14.

- 58Lauwaert, “Hedendaags sofisme en de arme ervaring”, 214.

- 59For a view on the status of film in the Flemish margin in the years before the Filmparties, see: G. Bakkers, “De televisiejaren van Eric de Kuyper, Deel 1: Over de BRT”, Sabzian (30 October 2019).

G. Bakkers, “De televisiejaren van Eric de Kuyper, Deel 2: Van Kort Geknipt naar De Andere Film en de vriendschap met Dirk Lauwaert”, Sabzian (4 December 2019).

G. Bakkers, “De Andere Film en Kort Geknipt, of hoe de marginale film zijn intrede doet in de Vlaamse huiskamer”, De Witte Raaf, 191 (January-February 2018), 21-23.

H. Asselberghs, “Alles wordt anders”, Jubilee - MuHKA 2007/1987/1967, D. Roelstraete (ed.) (Antwerp: MuHKA, 2007), 228-231. - 60The cutting-edge status of the Stuc programme, and thus of the Filmparties, is proven on the following evening, in the same room, by one of the very first performances of Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich, the early breakthrough piece by choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker.

- 61The same programme, with the same title, took place a day earlier at the Nieuwe Workshop, the Brussels platform for experimental art forms.

- 62In the brochure accompanying the third Film Festival, the following texts explicitly deal with terminology:

E. De Kuyper, “De marginale film. Het einde van de cinema?”, originally in: Streven (February 1970).

R. Campbell, “Eight Notes on the Underground”, originally in: Velvet Light Trap (Fall 1974).

J.W. Locke, “Independent Film, Experimental Film, Avant-Garde Film: a Clarification”, originally in: Parachute, 10 (1978).

J-F. Lyotard, “L’acinema”, originally in: D. Noguez (ed.), Cinéma: théories, lectures (Numéro spécial de la Revue d’Esthétique), (1973).

In the brochure accompanying the first Filmparty, one two-volume text mentions the issue of classification: E. De Kuyper, “Le mauvais genre (Une affaire de famille)” and “Le mauvais genre (suite)”, originally in: Ça-Cinéma, 18 and 19 (1979-80). - 63D. Lauwaert, “A Filmparty. Underground Film”, A Filmparty, (Leuven: Kultuurraad vzw/’t Stuc, 1982.

- 64Ibidem.

- 65Ibidem.

- 66Ibidem.

- 67D. Lauwaert, “Filmparty Three”, Filmparty Three, (Leuven: 1984).

- 68Lauwaert, “A Filmparty. Underground Film”.

- 69D. Lauwaert, “Filmparty Two”, Filmparty Two, (Leuven: 1983).

- 70Lauwaert, “A Filmparty. Underground Film”.

- 71Ibidem.

- 72Lauwaert, “Filmparty Three”.

- 73Lauwaert, “Filmparty Two”.

- 74Lauwaert, “Filmparty Three”.

- 75Ibidem.

- 76Arlene Croce, The Fred Astaire & Ginger Rogers Book, (New york: Outerbridge & Lazard, 1972).

This text is part of Herman Asselberghs’s doctoral research within the Intermedia research unit of LUCA School of Arts.

Image (1) from Der Tod der Maria Malibran (Werner Schroeter, 1972)

Image (2) from Wavelength (Michael Snow, 1967)

Image (3) from Hall (Peter Gidal, 1969)

Image (4) from Eaux d'artifice (Kenneth Anger, 1953)

Images (5) and (6) from Follow the Fleet (Mark Sandrich, 1936)

Images (7) and (8) from Le sexe qui parle (Claude Mulot, 1975)

Images (9) and (10) from Notes for a Letter to Angelina Jolie (Herman Asselberghs, 2018)