Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans

This song of the Man and his Wife is of no place and every place; you might hear it anywhere, at any time.

For wherever the sun rises and sets … in the city’s turmoil or under the open sky on the farm, life is much the same; sometimes bitter, sometimes sweet; tears and laughter; sin and forgiveness.1

This introductory intertitle, in which Lotte H. Eisner discerns a “typical” Carl Mayer touch,2

allows us to read in Sunrise (1927), far more than its inconsistent “philosophical” pretext, its major signifying articulations – namely, and in order of appearance: dramatis personae, but not characters in the traditional sense (the absence of names reduces the introduction of individuals to pure roles, networks of functions and attributes); time, but not history (the narrative refuses any relation to a real chronology, any temporality beyond the segmentation on which it is founded: the times of day); places, but not geography (purely fictive locations, referring to no extra-filmic reality); and finally the film’s tones, the curious “mix of genres” it produces.

Those dramatis personae, if we are to believe the subtitle (A Song of Two Humans), number only two. But since the central stake of the film is not the constitution of the couple, but rather its being put to the test, a third party must inevitably intervene: the vamp, whose role is to endanger the relationship of the man and woman. Beyond this classic triangle, there appear, strictly speaking, only “extras” – an undifferentiated mass of villagers or city-dwellers, reduced to their professional activities (waiter, hairdresser, manicurist, photographer...), lacking any decisive influence on the narrative, with the exception of the old man who allows the happy ending (his intervention is nothing short of miraculous).

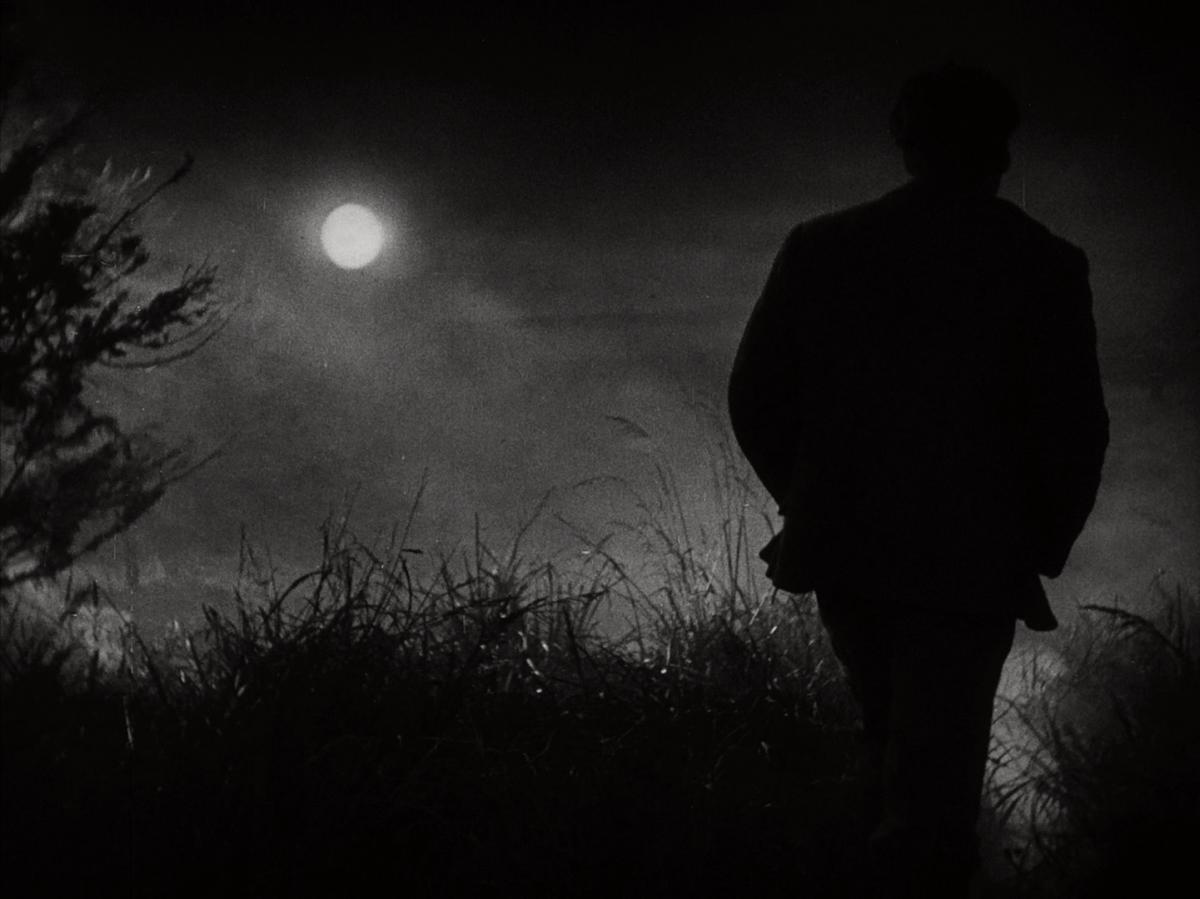

For a plot meant to unfold in perfect continuity over the course of 35 hours, the play with time – i.e., of light – constitutes a dramatic schema of the highest order. Dusk: the man abandons his wife to meet the vamp. Night: the lovers cook up their criminal plan. Day: the man tries to kill his wife, and rediscovers his love for her. Night: the wife drowns. Sunrise: she is found, the couple reunited. It would seem that Murnau chose not to include two transitional moments (the sunrise following the night spent with the vamp, and the dusk of the day in the city) so that the framing device – “the sun rises and sets” – could retain its strength of contrast between the death and the rebirth of love. Rather than expressing dramatic actions or moments (for instance: the murder attempt – diurnal; or the tenderness of the first images of return – nocturnal), day and night exercise their greatest metaphoric power over the two women. Fair and gentle, the wife is designated as the “daughter of day” in the remarkable shot where, in a sunlit courtyard, she throws grain to the chickens while her husband watches her from inside, through the doorframe. Associating darkness of hair with darkness of spirit, the vamp will remain – apart from her final morning departure, which visually expresses the situation’s reversal – she who lives by night, thus explaining her striking resemblance to a cat in the shots where, in order to observe the man’s return, she places herself in the tree that overlooks the crossroads.

Sloping floors (allowing splendid deep-focus effects), studio fog, fake moon, a village straight out of an expressionist film... In Sunrise Murnau, free of every realist concern, uses a limited number of places, each easily recognisable, as the figuration of the interpersonal relationships that join and disjoin in the course of the film. The most notable systematisation, from the viewpoint of spatial distribution, is modelled – just like the temporal segmentation – on the opposition of rivals: the wife is associated with the country, while the vamp has the city as her domain. A “middle term” is eventually added to these two locales, in order to demonstrate their (dis)junction: the lake. Sunrise is, in relation to its imaginary topography, the story of two displacements. First, the vamp moves to the country, where her presence is scandalous (“Several weeks had passed since her coming and still she lingered”), and where she is forever a foreign body – this is what we see (more than in the suspicious, contemptuous or outrightly hateful gazes of the peasants) in the close-up of the prints left by her high heels in the marsh’s mud. The second displacement is into the city, where various signs indicate to the couple their fundamental difference from it: menacingly in the episode of the accident, amusingly with the peasant dance scene. Two superimpositions, rupturing the place where they appear, are thus set in a mirror relation so as to confirm the respective characterisations of city and country: the mirage of the city behind the vamp as she tries to persuade the man to follow her there; and the “vision” of rustic happiness imagined by couple as they exit the church wedding.

The changes in tone that are very striking in Sunrise – uplifting or upsetting, depending on which critic you consult – are not merely accidental, or arrived at according to the economico-aesthetic principle whereby a “light” scene must inevitably break the tension of a tragic one. After a long (melo)dramatic part, the hairdresser episode inaugurates a string of gags (the photographer’s statue, the pig and the cook, the pesky shoulder straps) that function as so many signs of the devil-may-care atmosphere in which the couple revels. So it is not a matter of indifference that another comedic passage arrives just before the film’s ending (the jealousy shown by the rescuer’s wife before the kisses exchanged, in all innocence, between her husband and the maid): this marks the return of gaiety exactly where it had previously disappeared; or, even better, it takes up, in a buffoonish mode, the very pretext of the film – the triangle – which it thus manages to dedramatise.

All these elements, rigorously set in place, are combined in an overall structure that can be labelled leaving/returning... A leaving/returning which covers much more than simply the lake crossing, and whose veritable hinge is the fairground sequence: the camera tracks in, under the entranceway of Luna Park, and continues in a pan to the right toward a fountain, with the fair rides in the background; it exits, in a strict inversion of the same movement, with a pan to the left, followed by the beginning of a track out. Sunrise thus sets in place, in a determined order, a series of elements in relation to which a second movement has the function of repeating and varying them in reverse. The following description does not pretend to be exhaustive (its numbered fragments cover everything from simple series of shots to subtly arranged sequences): at most, it tries to render evident the structural game of symmetry.

1. The city vamp spends her holiday in the village (her journey suggested in the opening shots: trains and boats).

2. The vamp prepares herself; she leaves her abode and observes the villagers at their windows; she whistles for the man; he departs, making his wife cry; flashback to the idyllic life of the young couple before the vamp’s arrival.

3. The man and the vamp meet in the marshes; they dream up their murder plan; the vamp gathers the reeds that will save her lover.

4. The man and his wife go out boating; alternating montage with shots of the riverbank (dog episode); the man is about to kill his wife, then returns to rowing; montage: characters/boat coursing through the water.

5. Arrival on the other side of the river; the couple take the tramcar.

6. Numerous city sequences (in the café, at the church, with the hairdresser and the photographer).

7. The fairground.

6’. The city.

5’. The couple once again ride the tramcar, occupying the same places they had on their inbound trip.

4’. Return by boat; alternating montage with shots of the city (where a storm brews); the wind too violent for the vessel; the man takes the oars; montage: characters/boat coursing through the water.

3’. The man fixes the reeds to his wife; the boat overturns; the man looks for her with the help of villagers; the reeds floating on the water’s surface offer proof that she has drowned.

2’. The vamp prepares herself; she leaves her abode and observes the search; she whistles for the man; he, weeping over the death of his wife, begins to strangle her; but the wife has been found; the rescuer recounts his adventure (in flashback).

1’. The vamp leaves for the city.

Ideologically, Sunrise’s formal doubling designates the recommencement of love, which is to say – sunrise of the American film? – the return to the correct path of Christian marriage. The words of the priest, in the church that the married couple has entered as if by chance – “God is giving you, in the holy bonds of matrimony, a trust... Keep and protect her from all harm... Wilt thou LOVE her?”3

– offer, in a condensed form, the presumed ethical values of Murnau himself. This theme of remarriage is developed by numerous city scenes, not without, at times, a certain mushy sentimentality: in the church this goes all the way to saturation-point (the spouses’ consent, the woman’s “wedding” bouquet, bells ringing as the couple leave), in front of the photographer’s window (contemplation of souvenir portraits) as well as inside his studio (“She is the sweetest bride I’ve seen this year”) … not to mention the lyrical flights of the man on the return tramcar ride (“We’ll sail home by moonlight – another honeymoon”).4

According to this interpretive template, the storm would be nothing other, both literally and symbolically, than Heaven’s punishment for the forgetting of its law.

But psychoanalysis can offer another reading of the film’s structure of repetition – looking less to the compulsion of that name (i.e., the compulsion to repeat) than to the psychic processes of denial. What repeats, according to the principle of symmetry I have outlined here, never repeats in an identical or hallucinatory fashion – such as happens with the originary shock experience in traumatic neurosis – rather, it always modifies itself significantly, and always with the same general orientation, as if each element of returning had the function of effacing an element of leaving, as if it is a matter of the man systematically erasing the manifestations of his initial desire. Therefore it is the storm, and not himself, that is responsible for the drowning; it is for the rescue of his wife that the reeds serve their true purpose, not for his original murder plan; and it is the vamp whom he will finally attempt to kill, not his wife.

With the elimination of that troublemaker, the seductress, the film’s second “volley” folds itself entirely over the first: the unbearable wound opened up in the social order by the insertion of the Other is thus sewn right back up. The sun, over which the word FINIS is printed, begs us to euphorically imagine the rebirth of harmony and the “time regained” of happiness. But to imagine is not to see, because if the situation has returned to its previous status quo, Murnau never shows us – with the exception of the flashback noted in the summary – the couple’s daily life. “Happy people have no story”?5

Equilibrium is only interesting when menaced by disequilibrium? Leaving-returning, this strange palimpsest where two writings are rendered reciprocally unreadable, in the effort to win back that initial whiteness of a time where “nothing ever happens”... Sunrise refers to nothing but its own, dazzling, formal trajectory.

- 1The final six words are not part of the film’s English intertitles; Kuntzel may have derived them from a French-translated print. [translator’s note]

- 2Lotte H. Eisner, Murnau (University of California Press, 1973), 180. [translator’s note]

- 3Kuntzel’s transcription of the French intertitles again slightly differs from the original English: literally translated, Kuntzel has “May God bless your union... Protect her... Promise to love her always”. [translator's note]

- 4Kuntzel’s transcription, once again, is more obviously poetic than the English original: “Nous voguerons au clair de lune pour une autre lune de miel”. [translator’s note]

- 5“Les gens heureux n’ont pas d’histoire” is a line from the famous Charles Aznavour song, “Perdu” (1960). [translator’s note]

Many thanks to Adrian Martin