Meeting Charles Burnett

In 1964, twenty-year-old Serge Daney travelled to the United States together with his friend and co-operator Louis Skorecki. Both authors had a specific objective in mind when undertaking their intellectual voyage: as youngish reporters, they were to interview the last cohort of Hollywood’s Golden Age filmmakers, intended for publication in the now iconic Cahiers du Cinéma. After convening and conversing with filmmakers such as Howard Hawks, Josef von Sternberg and Leo McCarey, Daney later described this adventure in an interview with Serge Toubiana1 as being motivated “by the same belief that what is valuable [in cinema] is necessarily of the ‘present’.” The very fact that these filmmakers were still alive, Daney thought, was enough of a reason to undertake a personal interrogation of the wonderful films they had made.

Some of the encounters that followed, of course, turned out to be quite disillusive. As Daney himself later put it, “it seemed as if we had experienced the cruelty of Hollywood, of the system, and we knew which side we were on.” Daney’s encounters with figures such as Leo McCarey and George Cukor, for example, stand out as particularly painful: McCarey had become a yoghurt-spilling, decrepit old man, while Cukor had become wholly conditioned to read artistic success solely in terms of box office sales.

Charles Burnett, now at the age of 73, must have offered the exact opposite of the fleeting figure shown by McCarey and the compliant Cukor. Traces of his age seem nearly non-existent: he exerts an impressive youthful presence, speaking in a gentle, soft voice, in a bright, life-affirming fashion that one would tend to associate with the fervour of an idealistic debutant rather than with the quiet acquiescence of a veteran. Burnett, too, had his first-hand experience with the Hollywood machine; he too speaks of the frustrations bound to the studio system and the pressures filmmakers feel they need to assimilate to. Yet, uncharacteristically, Burnett chose to remain active on both sides of the system.

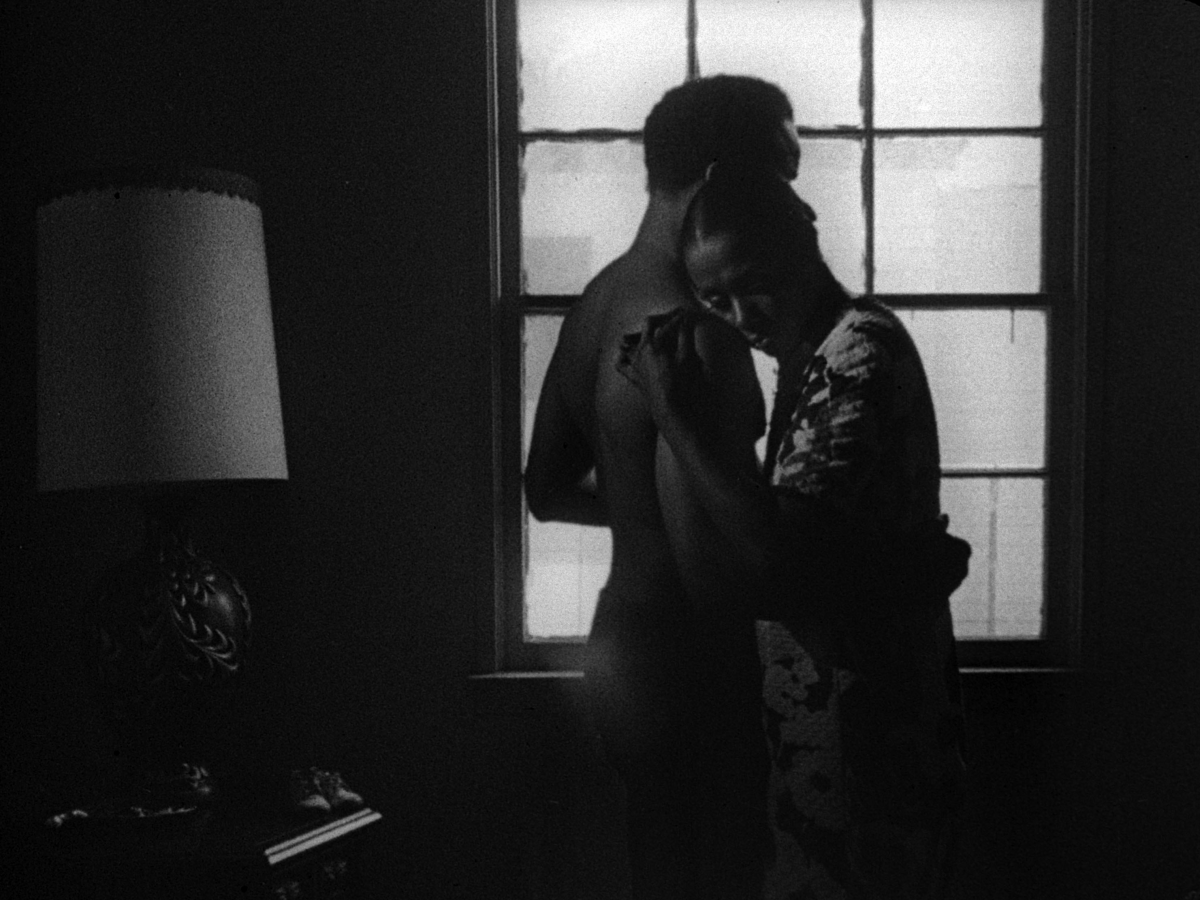

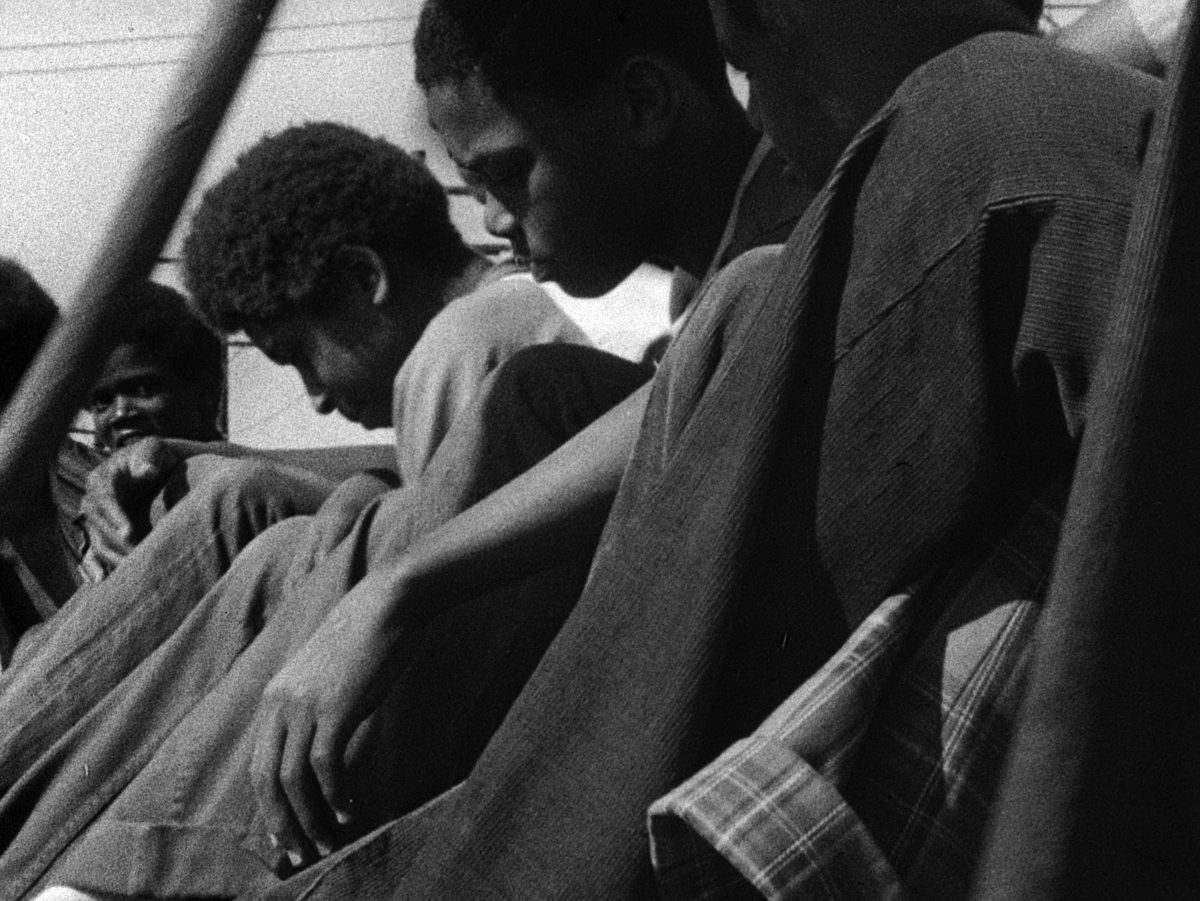

Almost a year ago now Sabzian met up with Charles Burnett in Brussels, on the occasion of a screening of a film he made at UCLA almost 40 years ago: Killer of Sheep.2 Taking place in Burnett’s native neighbourhood in Los Angeles, Killer of Sheep centres on Stan, a husband and father who spends his working days in a slaughterhouse. The film offers a suspiciously simple sequence of scenes taking place in the area: kids playing and throwing rocks at each other; men trying to move a car engine. We see Stan going to work, or sharing an intimate dance with his wife. In another scene, a joyous woman informs a group of friends of her impending pregnancy; when all has come to pass, Burnett’s protagonist simply resumes his voyage to the slaughterhouse. Killer of Sheep barely functions by way of any formal ‘plot lines’ as such: we are simply presented with a set of characters and locations, cyclically entering and leaving the screen. Although the social situation of Watts itself is not shunned, it doesn’t end up defining the characters; rather, Killer of Sheep focuses on something endlessly more bizarre, mysterious, beautiful and indefinable – a quality perhaps aptly described by the title of a Kiarostami film from 1992: Life and Nothing More….

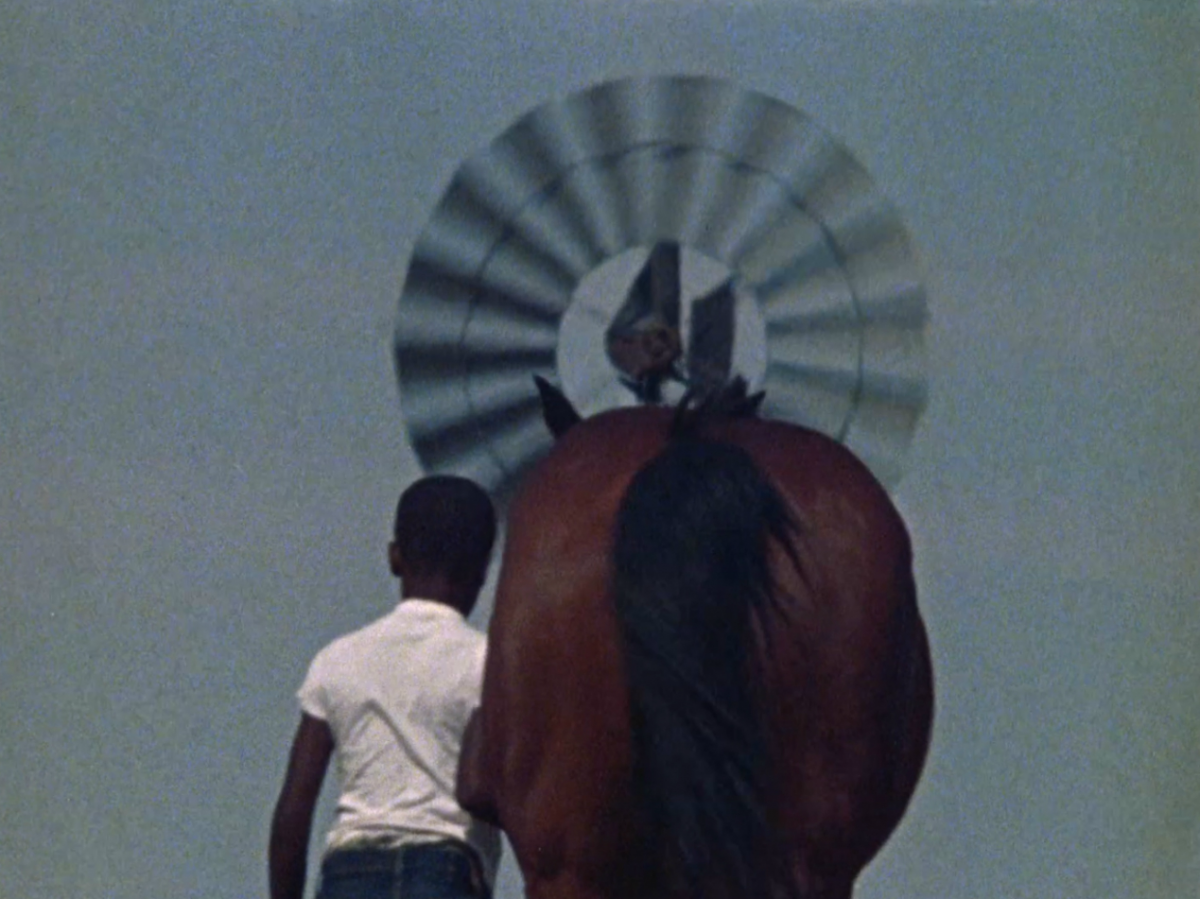

Although it is abundantly clear that his career was largely defined by this graduation film, and later by his bigger Hollywood productions, Burnett’s oeuvre also harbours films of a more independent nature – ‘independent’ is here used in the non-commercial sense of the word (those of an auteur one might say). Some examples are the incredible short film The Horse, set in the American South, and To Sleep With Anger (1990), a more spiritually oriented film that focuses on the struggles and vacillations of family life. The short film When It Rains (1995) is a wild and lyrical reflection on Burnett’s home community. Occasionally, it plays out very much like a little jazz piece, filled with creative exhilaration.

Reminiscing about his encounter with George Cukor, Daney concluded with the observation that he was still “astounded by the way we chose to love American cinema not by their norms but by our own”. A cherished film will always generate a set of reflections, formed by our own, projected norms. In a similar sense we had looked at Killer of Sheep according to our own norms and prepared this interview based on these projections. We had immortalized everything about Killer of Sheep and transposed Burnett’s iconography into myth. During the interview, however, Charles Burnett’s vivacity and insight show that he is as vibrant a filmmaker as he ever was, loving cinema merely on his own terms and reminding us that beautiful films don’t have to conform to any norms

Rid of any conceptual ballast, Burnett’s words always remain those of a practician rather than a theorist: his thoughts on the practice of filmmaking are always based on the experience of that very practice itself. Burnett’s vision on cinema is a straight-forwardly materialist one, constructed by a careful engagement with the material qualities of film as a medium. Burnett’s favoured theme of choice is always a determinate set of people in a determinate set of circumstances. In conversation, however, he reveals himself to be a person as capable of doubt as any other: a man worried about money, angered by the amount of time he has to spend on mundane matters – yet one who remains the author of that magnificent mystery named Killer of Sheep. Perhaps it is in this very mundanity that Burnett reveals his nature as a filmmaker: his films, after all, treat topics which are also often painfully commonplace, cut up and assembled in a particular order, and most of all treated with close attention. Maybe it is precisely this intimacy that provides his films with such an aura of genius.

Sabzian: Watts, the neighbourhood you grew up in, serves as the background for various films of yours. Since you were still quite young when you made your first films, what made you decide to make those films there, ‘at home’, instead of ‘moving out’ as many young filmmakers tend to do?

Charles Burnett: I didn’t have any ideas of becoming a filmmaker when I grew up. At a given point, I had ideas of becoming a still photographer, but I didn’t have the opportunity and I had soon forgotten about it after majoring in electronics. I assumed I was going to make a living as an electrician. I went to the movies a lot though, and I think it was the figure of the ‘cameraman’ that sort of interested me – the notion of ‘filming’. USC and UCLA were two schools nearby that offered classes in cinematography. I wanted to go to USC at first, since it was closer to my house, but it was way too expensive. UCLA wasn’t too far away – it was in Westwood, which is a very affluent neighbourhood, like Beverly Hills. So I went over there and started studying film. When I first got there, there were very few people of colour in the film department, and the kind of films the students were making were films I couldn’t really identify with. At the time, most of the students at UCLA were from well-to-do parents that hadn’t lived the same struggles as working class people had. Thus they were making films about alienation or about discovering their own sexuality, whereas, where I came from, other issues were more ‘important’, if you know what I mean. I just couldn’t relate to the films they were making.

There also was a group of more politically-minded students, though, most of them working-class. The school was a very diverse place back then, since it was cheap enough for anyone to go there. A lot of interesting people came to UCLA while I was a student there. It was at the time of the Civil Rights Movement: the Panthers, the Vietnam War… Predictably, some of the students became politicized and started making films about a variety of themes, such as exploitation and activism. I was a part of that group that was trying to use film as a means for social change. Later, there came a period in which a lot of people of colour joined the school. When these students started to make films, there was more of a concern about reflecting on the black experience in films. Since I was one of the older students in school at the time – I had been there the longest of all the students of colour – I was appointed as one of the student-teachers in the seminar group. We started off by simply making films about the environment in which we lived. These were mostly short documentaries or short fiction pieces. I saw Several Friends, for example, mostly as an attempt to create a longer piece that reflected things that were happening in my neighbourhood. I never really finished the film, but it was enough of a film to satisfy my curriculum requirements.

After Several Friends I made the film called The Horse, which was based on some of William Faulkner’s stories. Above all The Sound and the Fury, but also other work by Faulkner left a profound impact on my thinking. The Horse was influenced by one of my favourite short stories by Faulkner, The Bear. I wanted to make a film – because I was born in Mississippi but raised in Los Angeles – that took place in the South. I wanted to show the decadence and the transformation of the South at that time. The Horse was an example of that: it was a short film that I had made while I was working on my graduation film, Killer of Sheep. I received a grant to make it, but I used a part of the grant money to shoot The Horse.

Killer of Sheep, however, was mostly a reaction to the kind of films I was mentioning earlier: films about the working class made by well-to-do kids, often showing a distorted view of it. Most of the people of colour who were in film school were there to give alternatives to exactly this kind of Hollywood films which gave a distorted view on who we are as people. This was also the case with Killer of Sheep: its objective was to change the perception of coloured people, in spite of what Hollywood had created, this myth, and to give voice to people who didn’t have access to Hollywood to tell their story. The film was made for multiple reasons: to demystify filmmaking in the community and to introduce filmmaking to kids, notably by having children work on the sound and on other technical aspects of the film. We wanted to show people who were interested in making a change in the community, to use film as a means for social change. This meant showing the community without imposing one’s own values on the film: making it appear to be a ‘documentary’, where I just set the camera and shot a story – while everything was written, of course. ‘To present a slice of life.’ If people were interested in making a change in the community, it wasn’t going to come from the notion that ‘if A, B, C and D would happen, then…’ I wanted to show a film where I’m questioning this very supposition: this is what you see and how do you intend to change it? How do you ‘help’ people in the community? That was the ‘reason’ at the basis of Killer of Sheep.

In interviews you’ve mentioned James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men as an influence, visible in the fact that their position towards the communities they’re portraying is always one of an outsider. How did you establish your position of filmmaker in your own community? And how did you get your community to co-operate on the film?

I grew up with just about anyone who was working on the film. Not the two main actors though, Henry Gale Sanders and Kaycee Moore: I only met them when I started looking for a cast. But I knew everyone in the neighbourhood – I grew up in it – and the reason I chose them is simply because it was free: they were friends of mine, so I didn’t have to pay them. I mostly shot during the weekends when people were available, so as not to intervene with other people’s schedules.

Having gone to school – and a lot of my friends didn’t go to school, a lot of the neighbours never went to school – I realized that my entire outlook on life had changed profoundly and was different from the friends I grew up with. That was an instructive experience: I figured that you can make a film about a given community while also realising that this film will always remain an interpretation from your own personal perspective, which may turn out not even to be true. You have to be aware of the fact that everyone sees things differently. That which is meaningful to me, may not have a meaning for someone else. You have to push through, though, and try to find something that resonates with everyone.

Just about everything that happened in Killer of Sheep, did actually happen in real life: I just came to exaggerate certain aspects. Because of that, I knew that these were the sort of things that the people of the community would share. I took those events and put them into a narrative form or shape that would give you the sense of a narrative. I did this rather than superimposing a given plot, since the plot as represented by a Hollywoodian structure makes it pretty obvious that you are manipulating events. I didn’t want it to appear like that was what I was doing, or that was what the movie was about: I wanted it to appear as if it was a form of cinema vérité, where the camera was merely registering and we just recorded things that happened in front of the camera, even though it was all scripted. The idea was to present a reality where people could come to their own conclusions and ideas about what’s happening on-screen.

When you talk about the illusion of ‘cinema verité’, you mention that everything in Killer of Sheep was scripted. Was it scripted in a conventional style with dialogues written out, or was it drafted more loosely?

It was all scripted and storyboarded, so I had images of what I wanted to see. It came from my own experience as a kid, having rock fights and that kind of stuff. Have you ever been in a rock fight?

Sure.

I still have some scars from them. In that way you relive that experience and then you present it to an audience, since kids were still having rock fights when I shot the film. You recreate part of your memory and part of what’s actually taking place. You sort of ‘cherry pick’ things out of your memory and out of the present, whatever it is that works in the narrative. You have all those images and put the puzzle together as you’re writing the story. Rather than coming solely from your imagination, it really is a combination of imagination and a personal experience of the actual events.

It’s obvious that Killer of Sheep is part of a certain realistic tradition, visible in its tendency to simply start off with what you call ‘slices of life’. There is this one beautiful scene in the film, the dance scene with ‘This Bitter Earth’,3 where the realism suddenly acquires a magical intimacy. We’re thinking specifically of the dialogue with the woman; when the classical music comes in, the realism shifts to a more dreamlike, spiritual moment. What was your intent in editing this part in such a specific way, it being so drastically different from the rest of the film?

I wanted to have strong images in the film, which possessed a deeper meaning. The lyrical part of it came from my love for early documentary films, particularly Joris Ivens, Basil Wright and Robert Flaherty, who made poetic films using music and sound to heighten the film and pull you into it. I took a lot from that tradition.

I also wanted to add things that I had seen in the community in a way – for example, when the kids are jumping from roof to roof: they did that all the time in the area where I lived. When they were doing it on the apartment we were shooting in, I was not consciously aware of it, thinking: “I’m going to put that in the film.” But when you look at the images and you think of the ramifications of kids jumping over the roof, you’re anticipating a possible tragic situation: “What if one of them is going to fall?” You want people to experience part of what these kids experience. The second thought that comes to mind, however, is that these kids play a dangerous game. It reinforces the whole concept of kids having to play dangerous games in order to grow up. The games prepare them ‘to act as adults’: the younger kids see the older kids doing things, so it becomes an ongoing cycle of trying to make sense of these strange events or incidents while growing up to accept things that you didn’t question initially – while you should have questioned them all along. These are things that cause you to lose your sensitivity.

The gaze of the children in the film really seems to almost expose how strangely the adults are behaving.

I don’t think they look at it as being strange. They do look at it, of course, and in doing so they emulate their own behaviour. I think that’s one of the things I was trying to talk about. All these false notions and concepts that kids develop… They need some kind of text or guidance, someone who can tell them what it all means. For example, in the film an interesting conflict occurs between the young girls and the young boys. The girls didn’t like boys of their own age, and vice versa: the boys only liked the older girls. So we got them around each other, and we happened to have all girls and boys of the same age. This was troublesome, since they didn’t want to be intermingled in that way. We didn’t have to encourage them to fight or anything: they did it so wholly on themselves. They had this idea that ‘real’ girls were older, and so did the girls. The girls couldn’t care less when boys were younger. At a young age, they developed these problematic habits when dealing with the opposite sex, reliant on a distorted perception of it.

How do you see the child in The Horse? What we have here is a child that doesn’t rebel, but that seemingly does want to rebel; it is as if he’s up against grown-ups all on his own, and doesn’t want to become like them.

The film has something symbolic to it: the horse represents the Old South and the feelings this elicits in the child. Yet, on the other hand, he doesn’t mind being there, it’s almost as if he knows that the horse is going to be killed for a valid reason since it’s clearly sick and already haemorrhaging. His father is supposed to do this, out of tradition, or at least the owner thinks it would be fitting for him to do it. He kind of wants to see the tragic ending, but decides to close his eyes. While the process takes a longer timespan, however, he becomes curious and ends up seeing what he doesn’t want to see.

What is striking to us is that, as a film, The Horse feels like it is very deeply embedded in American culture, yet, on a more formal level, it feels more European, almost like a Bresson.

I think what influenced me more was a regional style of filmmaking. You try to separate yourself from a Hollywood tradition, which is both good and bad. It can be good because you can create your own influence and image, and you can have an impact in the industry. Yet at the same time, you become so far removed from the industry, marginalised almost, that people simply can’t identify with your work anymore – mostly when it comes to story lines. There were times when I would be looking for a job and they would say: "Oh, he’s an artist". ‘Artist’ is not a good word in Hollywood. It stands for those who don’t make money and only engage in obscure filmmaking. You don’t want to be ‘branded’ as an artist. When you’re trying to find a job, and they tell you that "you really don’t want to work with him: his films don’t make any money and he’s independent and hard to get along with," even if these things are untrue, Hollywood is still very good at spinning this narrative about you. They create a false image and thereby determine whether you’ll get a job or not.

I once had a job for a film called Nightjohn. I don’t think it’s ever been screened here. It’s about the American slave period. Disney, the producer, didn’t want to hire me for the job, but one of the actors insisted that I’d direct the movie. They hadn’t signed him yet, though, and he was also up for another part, which came first, so he just jumped on a different project. Still, Disney didn’t want me, but I had already signed. After directing the movie, the producer came up to me and said: “We thought you were going to be this really difficult, outspoken, violent… artist.” That was the kind of speech he gave me. He was surprised that I wasn’t all about that. The same thing happened with another Disney film. They came up to me and said there wasn’t enough money for hours worked overtime. They asked me: “Can you do it?” I said: “Yeah, we can do it.” Thus, every day, the cameraman and I were looking at the schedule, with the producer saying “You guys aren’t going to make it today, there’s just too much material.” Each day we’d come in before the rest, and do everything. They would keep asking us: “Well, how did you guys manage to do that?” Even if we’d made mistakes, we’d make up for them. It is a fact that people of colour have to do ten times as much as other people to survive: for the same money, you have to work harder and do better. And in the end they’re always surprised: they always have this illusion that you can’t do it.

What’s striking is that you have really seen both sides of the filmmaking world: worked on large-scale productions with Disney on the one hand, but on the other, you’ve also managed to make independent films. Do you have a stronger preference for small-scale, independent productions?

It’s more rewarding to work independently. You can find craziness on both sides, though. Producers can be just as nutty when they’re in the independent business: independent filmmaking doesn’t automatically imply artistic freedom. When you work with someone else’s money, you always need to mediate. Occasionally you’ll find a great number of people willing to identify with what you want to do, which is a little bit better than studio work. When I worked with Disney, they were very nice.

What would you guys like to do later? Directing? Feature films? Documentaries?

At KASK / School of Arts – the school we're currently studying at – the opposition between documentary and fiction is under constant challenge: documentaries and fiction films don’t have to be classified solely according to their respective disciplinary ‘expectations’. There’s one director, for example, Johan van der Keuken, a Dutch documentary filmmaker…

What’s his name?

Johan van der Keuken.

Yes, van der Keuken! He died, didn’t he? I met him!

As a filmmaker he’s immensely inspiring, we find. He didn’t care about the classification of films as fiction films or documentaries; what he cared about, above all, was improvisation.

Yeah, I met him several times. A really nice guy.

Where did you meet him?

I met him on various occasions. I may have met him in Holland too, or here [in Brussels]. When he was in California, I met him at UCLA – and I think I may have also met him at Billy Woodberry’s house.

Had he seen Killer of Sheep?

Yes, he had seen the film and we talked about some other things. I haven’t heard his name in a long time. I hadn’t thought about him in a while. Do you study his films?

He is definitely one of the most prominent authors at our school, both for teachers and students.

Good for you guys. You have a praiseworthy example. I was a big fan of Joris Ivens also. I’ve met him too – I don’t know what year it was when I met him and his wife. He was a good friend of Basil Wright as well.

You know what documentary festival you guys should attend? The Robert Flaherty Seminar. It used to travel around, but now it takes place in Upstate New York. You spend a week or so just looking at films and discussing them. It’s murder! You fly in at night, go to a party, and then you go to a screening late at night and they will talk you to death about it. They used to be really cruel. When you got up in the morning, you’d have breakfast and head right towards the next screening. Then you’d talk about the film, and maybe see another one… At some point you’d have lunch, but then you’d go to another screening. You do this every day, for a week or so, and by the third day, you wouldn’t know what day it is! If you’ve got your film screening over there, it’s even worse, since they will inevitably criticize it. Joris screened his China series there,4 and, God, he had asthma at the time, but he did take the criticism very professionally.

Are there any contemporary filmmakers you are particularly interested in?

I saw this one film, The Apple, by Samira [Makhmalbaf]. Truly beautiful, you should see it. Every time I feel bad, I look at this movie. You now hear those crazy people who want to bomb Iran, and when you think of all these kids, around the world, you can only think, “How could they want to do that?” Of all the films I’ve seen it’s the one I always return to. And it has nothing to do with structure or style. It’s just these two little girls, captured, not socialised. Just kids, you know?

- 1Persévérance (P.O.L. éditeur, 1994) appeared in English as Postcards from the Cinema (Bloomsbury Academic, 2007) and in Dutch as Volharden (Octavo publicaties, 2011)

- 2“Diagonal Thoughts”.

- 3‘This Bitter Earth’ by Dinah Washington

- 4Hoe Yukong de bergen verzette [How Yukong Moved the Mountains] (Joris Ivens, 1976)

This interview was held in April 2016 in Brussels.

Many thanks to Chloë Delanghe and Stoffel Debuysere

Images (1), (2), (3) and (4) from Killer of Sheep (Charles Burnett, 1978)

Image (5) from The Horse (Charles Burnett, 1973)