“I have never been a big fan of reality”

A Conversation with David Koepp

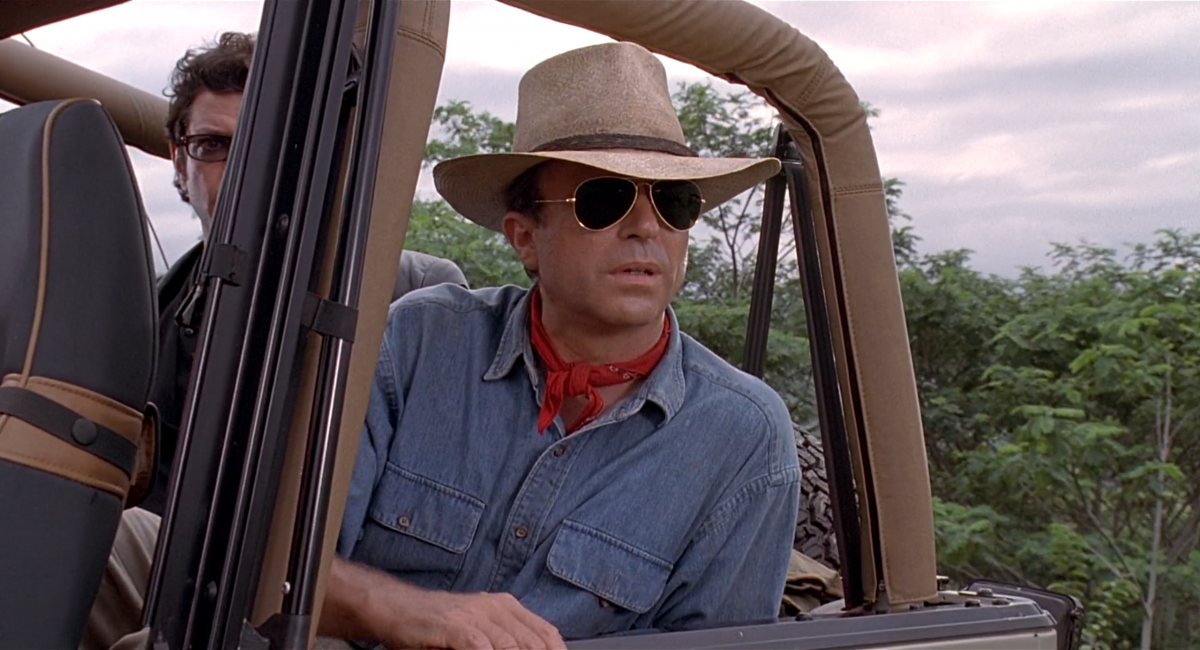

In May 2018, David Koepp visited Brussels for a talk about his work as a screenwriter and director. As a screenwriter, he is best known for his work on films like Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1993), Carlito’s Way (Brian De Palma, 1993), Mission: Impossible (Brian De Palma, 1996), Snake Eyes (Brian De Palma, 1998), Panic Room (David Fincher, 2002), Spider-Man (Sam Raimi, 2002) and The Mummy (Alex Kurtzman, 2017). His filmography as a director includes Secret Window (2004), Ghost Town (2008) and Premium Rush (2012). Sabzian met him in Brussels for a short conversation.

David Koepp: So you make films as well?

Gerard-Jan Claes: Yes, mainly documentaries.

I was going to say, what kind of films do you make? What was your last one?

Nina de Vroome: I made A Dog’s Luck, a short film about police dogs.

That’s cool. About how they are trained?

de Vroome: Yes, and how they live. But you only see the ‘faces’ of the dogs, there’s no talking, you don’t see any human faces.

In the whole documentary? That’s very Frederick Wiseman, that’s great. That must have been challenging, to string a narrative, but without human characters and dialogues.

de Vroome: There’s not much of a story. It is more about looking at the dogs, observing the choreography of their movements, the disciplining of their gestures, their experience of time, waiting for their bosses and obeying their commands. There is no real narrative; its starting point is observation. But it is just a small film, really...

That sounds interesting. I’m sorry, you don’t want to talk about your movie. I am sometimes tired of talking about myself. But what can I tell you?

Gerard-Jan Claes and Nina de Vroome: You once said, “screenwriting is about what you see and hear in a film.” What is the difficulty of ‘translating’ a novel into a script, making the movement from narrating from an interiority to narrating from an exteriority?

That’s it, exactly. The book is essentially what people think and feel, and the only tools you have in a movie is what you see and hear. You can get their thoughts literally if you use a voice-over, but you need to figure out ways to show how they feel through behaviour. The difficulty is that one action is internal and another external, and you are finding ways of turning everything inside out. Sometimes when you are adapting a book, what you really have to do is just take the general flow of the story and throw out the rest. Hopefully you’ll get a few good characters and a good premise, but the rest you really have to take out. Even if it is your own book. I wrote one recently for the first time. I finished it just a few weeks ago. What was fascinating when I started, was that I realised that for the first time in thirty years I was writing what people are thinking. Which was just delightful, I really enjoyed it. For the first time I could write from within someone’s head.

And when you adapt someone else’s book, is there still the ambition to translate a certain tonality that you found in the original book, or would you just keep a narrative skeleton, adding your own tonality as a screenwriter?

Tone is what you have to respect. I think that you owe the author of the novel really little, because we’re working in completely different media, with completely different needs. But the tone and spirit are the one thing you try to preserve, you should try to preserve. Because otherwise, why even bother with the book? The only time I can think of when someone really violated the spirit of the book was Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1964), which was based on Peter George’s Red Alert from 1958, a very serious pulpy novel about nuclear war. Famously, the more Kubrick researched it, the more insane it was to him and he said “this has to be a comedy, it’s ridiculous.” But I can’t think of another time that one completely changed the spirit or the tone of a book. Tonality is important and it is the thing to keep.

You are translating a world of words to a world of images, which is always exterior. You are also writing a story in which characters are performing actions and are placed in specific situations. Are you indicating the director how he is supposed to translate those words back into images? For example, in Jurassic Park, you have specifically paid attention to the way things are revealed. The first time we see the dinosaurs, there is an elaborate build-up to the moment the spectator actually gets to see them. We first see the expression of the characters discovering the creatures, the impact it has on them, before discovering them ourselves. Is this procedure of looking and revealing part of the script?

Yes, the screenwriter has a responsibility to describe all the images, to conceive all of them. With Jurassic Park, Steven [Spielberg] was working on the project before me. The great filmmaker that he is, he had of course brilliant visual concepts, so he contributed extensively to the development of the script. But in any script I still think it is the writer’s responsibility to take the first crack in any action or adventure sequence, and describe it in ways that make it seem visually come alive. When I started working on Jurassic Park, Steven already had a clear idea about certain sequences. So I was lucky in that regard. But normally I am always writing my first path of how I think the action scenes should be. You need to write in such a way that you are invoking images in the reader’s mind. Not just particular images, but mainly the rhythm in which you want them to occur. If the scene is going faster, you provide more space on the page because the person will start to read faster. Then their mind will be creating the movie as they read. I spend a lot of time with that, because it’s an essential part of screenwriting and I think too many writers just fall back on the lumps of descriptions, saying “the director will figure out the action scenes.” No, you have to figure out the action scenes first and you have to present it in a way that not just the director, but everybody that reads it, can see it. For example, I use a lot of white space on the page, break sentences midway through to imply that there’s a cut, any other tricks I can use to arrange the words on the page. That it flows like an action scene and not just a dead splotch of indecipherable action. Writing an action scene is a very particular skill. It’s craft.

You are thinking as a filmmaker then?

Very much. You are abdicating your responsibility if you don’t, if you just think “well, I will just write the dialogue.” That is not screenwriting. That’s dialogue writing. Screenwriting is when you write in images.

When watching other films, do you notice when this didn’t happen in the screenwriting?

No, it is really hard to separate writing from directing. It is also very hard to separate bad acting from bad writing. It might have been a perfectly good scene, but poorly paced and performed or vice versa. Or Tom Hanks did something marvellous with a mediocre line. It is really hard to separate. The director can really ruin the script and the script can ruin the director. Everything has to come together.

We were wondering about your writing process if you don’t start from a novel. Do you start with the development of characters, around which the outline of the story is draped or does it start with a skeleton of a narrative while characters, dialogues and details are filling in this conceived structure?

It depends, sometimes I think of the character first. Like a thing I just wrote is based on a guy I saw walking down the street once and I was thinking about what he might be like. You can start because a person occurred to you and then a series of events happen to that person or because of that person. More often I think of a situation and then think of the most interesting people to put in that situation dramatically. But for Panic Room, I read about safe rooms that people built in their houses to be safe from intruders. I just saw it in a newspaper and a couple of years later I thought “that should be a good movie,” and I set it in a house in New York, just like the one I’m living in. So that grew from a concept and then characters came to it. It depends, ideas can come from anywhere, from a situation, a person, something that happened to you once in your life.

Many theorists consider Jurassic Park to be a film that marked a turning point in cinema, i.e. the beginning of digital manipulated images in cinema. From then on, only the imagination of the screenwriter became the limit, reality did no longer pose limitations. Looking back at the last 35 years of filmmaking, how do you relate to that?

Cinema has always been manipulating reality, changing reality. Georges Méliès made A Trip to the Moon a hundred and some years ago. There were dinosaur movies long before Jurassic Park, but it didn’t look terribly realistic. Then it began to look photorealistic, which was rather amazing. I think it just opened up an era in which people wanted to experiment with that. So you got a lot of bad movies at first, because you wanted to throw the new tools at all sorts of things, to see: what can we make? Can we make a volcano? Can we make a tornado? Enough of those were bad movies. In the early nineties, the capability became much greater. After CG [Computer Graphics] had settled down some in that rampant use, it allowed all sorts of different things to be done, even using it to make things where you don’t see it. Sometimes you don’t even know that CG was used. Unfortunately, it usually renders a certain lifelessness to that effect. If you can figure it out without CG, it is always better, because it feels more real. So like any new tool, when sound came in, when colour came in, you rushed to apply it to all sorts of things and stories and see what it does to it.

Has it changed a way of relating to reality, the feel of reality?

In a movie sense you mean?

Yes.

I have always found the slavish devotion to reality a bit of a mystery. I don’t know why. People say: “Well, that doesn’t seem very realistic.” You are sitting in a room with a hundred of strangers, looking at a projection on a screen, there is nothing realistic about that, it is all fake. The actress is not real. This is all fake, every bit of it. The clothes they have on, the way they live, the make-up, it is all fake. I have never been a big fan of reality. I think that’s why we watch stories.

You say “I am not interested in reality, because film is made out of imagination,” but still in Jurassic Park there is a lot of space for breathing in this reality, this imaginative reality of the Jurassic Park, whereas in a lot of action movies nowadays there’s not this breathing in of imagination. There’s a development of action movies today focussing more on spectacle, attractions, explosions and chases, and less on the constitution of a world that really exists on the screen.

Most movies are bad. That’s just the way it is, most movies in all languages, in all countries are bad. Just as most art is bad. But bad paintings end up in someone’s garage, and no one ever sees them, whereas bad movies still have a 40-million-dollar ad campaign. They still go out there. Jurassic Park was a little lighting in a bottle. It managed, aside from its great spectacle, to really capture people’s imagination and emotion. When you first see the dinosaurs, it is quite beautiful. It wasn’t just that you were seeing a new technology, like the characters on the screen you felt a sense of awe and wonderment. That’s very special. I don’t know why it happened and why it doesn’t happen at other times.

Watching Jurassic Park again recently we were just amazed by the patience of the story. It takes 45 minutes before the gates of Jurassic Park open. In blockbusters that we watch today, you are immediately assaulted by overwhelming action scenes. Did you experience a development in that sense, regarding what is possible in storytelling?

Everything is better when you have to wait. I remember after we did the first movie, we were going to do a second movie and people would write letters saying what they thought, how they thought the sequel should be. There was a classroom of ten-year-olds, that wrote a bunch of letters: “Whatever you do, don’t take so long to get to the island this time.” I was like: “What is this, you loved the movie, right? Just be patient, because things are better when you wait.” Steven and I worked on building anticipation, letting the viewers fill it in with their own mind until it is time for the pay-off. But that’s a constant struggle. How long can we pull off to build that? When a writer and a director are working in sync, they are balancing that. Doing enough to lure the audience in and get their interest and get them leaning forward, but never so much that you blow it and they can’t be satisfied. They need to be satisfied every ten minutes. That’s the dance of great screenwriting.

I remember when I pitched the first story for the first Spider-Man, I said: “and also… it is going to be about 45 minutes before he’s really Spider-Man.” And they said: “Can’t you do it in 10?” “Yes, we could, but it won’t be as good.” If it’s longer, drag it out, delay as long as you possibly can and it will be a better story. The problem with big movies is that they’re so much more expensive. I think Jurassic Park was 56 million dollars when it was made. Granted, that was 25 years ago, but now it would be 300 or something ridiculous. They want a big action sequence up front and every ten minutes there needs to be a thrilling event. But also what Hollywood studios want to make is so different than it used to be, and frankly, it is much less interesting. To me and to audiences as well, as long as they still go, the Marvel model is with us now and that’s what the studio’s want, desperately. Because they either trained audiences, or have been trained by the audiences, or it is some vicious cycle that we’re in. I am directing a movie in the fall, it is a scary movie, there’s a frightening opening and then for 45 minutes really nothing happens. Things happen, but not scary or dangerous. And it works, it’s OK. But I’m making that movie for 5 million dollars. Because a major studio would not in years go for a scenario like that.

Do you consider the work on your own films and for blockbusters as separate worlds? Do you see yourself as a craftsman when you are writing a blockbuster and as an artist, an ‘auteur,’ when you are working on your own projects?

You certainly are allowed more on a smaller film. And yes, you chose pretty good words, the work is craftsman-like on a big budget blockbuster. But it is not just because there are so many more people involved, these film studios are owned by vast international corporations with corporate destinies at stake and you are responsible to that. I don’t know how much more of that I’ll do. I’m old and I used to be innocent, but I don’t know how interesting it is to be working like that.

Is there still a sense of satisfaction as an ‘auteur’ within this industry writing?

No. I get the first two drafts. Those are mine and I love them. Then you send them off into the world, just like your own child. They will meet nice people and they are going to meet a bunch of jerks. And you hope that things go well for them. But if it is a big expensive movie, after the first two drafts I say a little bit goodbye to the script. Because it might become better than what I had in mind, it might become worse, but it will certainly be different.

But there’s still a sense of negotiation in the sense they don’t want an accountant to write the script. They want you, because you have a certain craftsmanship.

Of course, it is. But a part of what they pay you for is the ability to disregard your opinions. When you are highly paid for those kinds of movies, part of the expectation is “give us what we want and if you don’t we’ll fire you. And we’ll also change it.”

Do they know what they want?

No. It is a frustrating kind of work. I don’t think there’s much more of that stuff in my future.

Is there also such a thing as a checklist of narrative elements? For instance, there’s the broader story line and then you provide it with smaller story units. In Jurassic Park, for example, the desire of having children is an underlying storyline.

Characters need to want something. What they want is at odds with what someone else wants. Great, then you have conflict. I think someone asked Mike Nichols once “why do your movies always have so much drama involved?” Which is a stupid question. He patiently looked at the person and said “well, I can’t tell stories about how well it is all going.” You think Jurassic Park is a movie about dinosaurs but it is also about humans. There are kids in the story while at the same time there’s a character who doesn’t know what to think of kids. Maybe he doesn’t like them, maybe he doesn’t want to be near them and doesn’t feel comfortable with them, so then there’s conflict. Every scene is conflict of a minor type and of a major more ongoing type. So in short, what do your characters want and what is stopping to get them to it? Or what do they desperately want to avoid and how do I put that in front of them?

Did you look for it in a sense of a thematic coherence, like “life always finds a way?” 1

It seemed to have a lot to do with that, yes.

Is it something you talked about?

Sure. It is nice if it’s all fruit of the same tree.

Let’s talk about dying.

Dying?

There’s a difference between who’s dying in the novel Jurassic Park, written by Michael Crichton, and who’s dying in the film. How did you decide that? Is that a decision you make collectively with the producers and director?

Well, in a movie it’s different. You actually see the characters. It is easier to kill someone in a book than it is in a movie. And also, our tone was a little bit lighter than in the book. The book is a bit darker. In part because it was going to be a big expensive movie, in part because of the sensibilities of the director and in part because we wanted it to be a family experience, we killed less people. Because you get to like them in a different way. We didn’t want it to be quite as macabre as the book was. But it also goes to your world view. Michael’s world view is a bit darker than certainly Steven’s and even mine.

Were there discussions about which character would get to live and which one would have to die?

In the case of the Jeff Goldblum character, both of us said in the first meeting: “We can’t kill him, right? He is way too much fun.” We wanted him around because he is an entertaining character, he is really fun to write for.

But then there’s a danger of predictability. For example, the lawyer…

You know he’s dead.

Yes

I think the hunter, Muldoon, was as far as we went. Killing a character we actually kind of liked.

He actually gets a slow killing. It was not the most…

It was very unpleasant. But it was all fake! He’s OK now… Oh no, he’s not, he passed away actually. Anyway… I think I have to get going for this talk at CINEMATEK.

Thank you for your time!

- 1In Jurassic Park, doctor Ian Malcom warns the billionaire John Hammond. Even though they only breed female dinosaurs in the park, “life always finds a way.”

This interview took place in May 2018 in Brussels.