“Originally planned as a ‘comedy’ about romantic isolation à la Eric Rohmer’s Le Rayon Vert (1986), the mordantly titled Vive l’amour indeed retains the skeleton of its inspiration – a woman’s emptied life, the interminable pregnancies of happenstance, an eleventh-hour glimpse of human connection tempered by a flashflood of searing emotion – even if it jettisons the skin: there’s more talk in Le Rayon Vert’s first ten minutes than in Vive l’amour’s entire duration. As for music cues, there are none at all. In Tsai’s Taipei, the electro-drones of car alarms and street-crossing signals compete with the constant chirruping of cell phones and doorbells to blot out lyrical cues and melodic coercions. When a whisper of muzak is finally heard – an hour into the film, in the salesroom of a columbarium – it’s as if the dead had suddenly begun whispering, beckoning, and Tsai has his characters beat a hasty retreat. Ancestral voices are to he avoided at all costs, and the faceless fury with which contemporary Taiwan, where graveyards are full but apartment houses empty, is bulldozing its various pasts – social, architectural, spiritual – force Vive l’amour’s friends and lovers into a constant state of directionless motion.

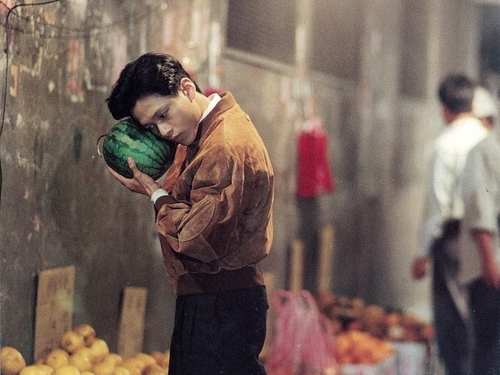

There is, nevertheless, a passionate determination throughout Tsai’s work that these characters arrive – somehow, sometime – in each other’s arms. But even if gratification is forever postponed, the waiting is imbued with a kind of tantric glee: though Vive l’amour’s oppressive, Antonioni-derived sense of urban, architectural nausea serves mainly to place potholes in its pilgrims paths, the ways they manage to skirt and dodge and eventually collide or nearly miss one another is effected with an almost Tati-esque choreographic grace. Connections, once made, are always tenuous, emotionally cryptic, and subject to revocation, and it’s not until very close to Vive l’amour’s end – when Hsiao-kang finally summons the courage to steal a bit of pleasure while his inamorata, the aloof Ah-jong, lies sleeping – that Tsai shows his hand at all.”

Chuck Stephens1

“Vive l’amour, the first one I saw, still seems to me the finest – the most rigorous, the most disciplined, the most fully thought and felt. The patterning, whether of the overall sequence of films or within each separately, is fascinating in itself, but it never hardens into mere formalism. The symmetry is always at the service of the sense. [...] Among the unforgettable moments of modern cinema is (of course!) the kiss – the only kiss in the entire film, hence very decidedly privileged. It is almost the film’s climactic moment, the film’s one expression of total (if necessarily unreciprocated) love. Almost, but not quite. Tsai leaves us (rightly, I think) with Lin, and perhaps the most audacious ending I have ever encountered in a fictional film.”

Robin Wood2

“In an ending that has now become legendary, Tsai stages a two-minute tracking shot of a long high-heeled walk taken by the female protagonist in a park, followed by one static medium close-up of her crying for about six minutes. An essay by Chu T’ien-wen, Hou Hsaio-hsien’s regular screenplay writer, vividly captures the excitement greeting the release of Vive l’amour in Taiwan. Entitled ‘A New Milestone,’ Chu’s essay recounts a discussion among a group of filmmakers and critics after the screening of Vive l’amour. One director asked repeatedly if this was a rough cut and if music were to be added.”

Song Hwee Lim3

Shelly Kraicer: Does it make sense to talk about a “Taiwanese Art Film Style”? I’m thinking of Hou Hsiao-hsien, who set the model: long takes, stationary camera, medium to long shots, location shooting. Do your films participate in such a style or do they resist it?

Tsai Ming-liang: I don’t think much about my own film style, or the relationship between my style and the so-called Taiwan Art Film Style. My films are influenced by my own theater work. When I was doing theater, before I started making films, I always used very realistic props and a very realistic acting style, and I never changed sets – I used sets that were almost like film sets. Also, the theme of those stage works was always very film-related. For instance my first stage work was called Instant Noodle. It was about this kid who loves films so much that he spends all of his money on film festival tickets. But then there is no money left for him to eat, so he always eats instant noodles. At night he dreams about cinema. We used an 8 mm camera to film all the classic films that I like, and projected it on the mosquito nets around him to symbolize his dreams. My first stage work was very cinematic.

On the other hand, when I started to make films I found myself pretty much influenced by the stage. It’s the long concept of space and time, and the stationary camera. The latter also had something to do with the locations I used. Usually I film in a small room, and as you know there is very limited space for me to move the camera around. On the other hand, if a character is moving outside in a larger space, the camera of course will follow him. So whether the camera moves or does not move has something to do with the characters. In that sense, I feel a kind of freedom. I don’t chose a deliberate style, of using long takes without interruptions. That is the origin of my aesthetics, it’s not from having some preconceived idea about film style.

Tsai Ming-liang in conversation with Shelly Kraicer4

- 1Chuck Stephens, “Intersection: Tsai Ming-liang’s yearning bike boys and heartsick heroines,” Film Comment, nr. 32, 1996, 20-23.

- 2Robin Wood, “Vive l’amour,” Film International, nr. 19, 2006, 44-49.

- 3Song Hwee Lim, Tsai Ming-liang and a Cinema of Slowness (Honolulu: University of Hawai Press, 2014), 124-125.

- 4Shelly Kraicer and Tsai Ming-liang, “Interview with Tsai Ming-liang,” Positions, nr. 2, 2000, 579-587.