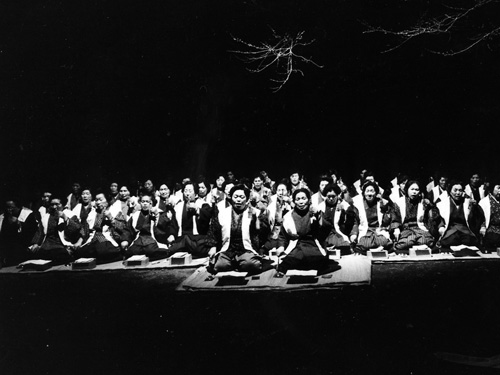

“The documentary we have been shooting for the last seven or eight years hopes to recreate the natural features – rice, earth, water – and recreate the stories sleeping in the hearts of the villagers. Itsutsudomoe Jinja Daihokai is, in this film, what could be called a (as if it were) a film within a film. I use the word “theater,” but on this stage where everyone participates and there is not a single spectator, we consider it a vivid ceremony that exceeds the framework of simple drama.”

Ogawa Shinsuke1

This collective of filmmakers, founded in the late sixties, under the direction of Ogawa Shinsuke, chronicled with remarkable dedication some of the major political and social upheavals in Japan’s ‘season of politics’ from the 1960s through the 1970s, including the struggles of the student movement and long-term resistance by farmers in Sanrizuka. Ogawa Productions’ work aspired to collective decision-making, achieving an unusual level of engagement with the people they filmed. They aimed to make independent and partisan films, while at the same time developing alternative ways for distributing, screening and discussing their work.

As the Sanrizuka conflicts waned, the members of Ogawa Productions relocated to the village of Magino in the prefecture of Yamagata in North Japan, where they lived together for the next decade, farming and filming. This resulted in a monumental and open-ended film that brings together all the ideas and themes developed in the previous works of the collective: village life and heritage, farming and science, history, oral tales, the customs and spiritual life of the people and their connection to the land, as well as the long culture of dissidence of the farmers and their resistance to authority. The present, historical and mythical times of this place are layered through the storytelling of the people, the cycle of rice harvests and the changing seasons. An archaeological excavation opens up a meditation on history as the film expands following the rhythm of the slow growth of crops and the passing of the years. The people tell their stories, recite ancient myths, and come together under Ogawa’s direction, to re-enact fictional sequences about ghosts and gods (also featuring actors, such as Hijikata Tatsumi, the founder of Butoh). In order to screen and celebrate the result of their work, Ogawa Shinsuke imagined and constructed a theatre made of wood, grass and mud, which he named The Theatre of a Thousand Years.2

A publicity flyer for The Theater of a Thousand Years describes the motives behind building a temporary exhibition space for a single film:

Welcome to the Theater of a Thousand Years! Considering the freedom of cinema, should not the places cinema is shown have that freedom as well? This is the conception of The Theater of a Thousand Years. From the end of production to the screening of the film, most filmmakers entrust their films to the hands of other people, but here this activity is being handled from the filmmakers’ side.... It’s the romance of cinephiles that a theater could be devoted to a single film. This Theater of a Thousand Years is the first embodiment of what cinephiles have long dreamed of. To be specific, it could be said that this film is utterly wrapped up in the world of Magino Village in Yamagata Prefecture. The space of this theater is surely the same, and the embodiment of that dream entirely sweeps away one's feelings toward the movie theaters of today.

Abé Mark Nornes3

« Les méthodes d’Ogawa opèrent un retour aux intentions premières du documentaire. En quoi consiste un documentaire, sur quoi repose-t-il ? Il repose d’abord sur une grande affection et une profonde admiration pour son sujet. Ce principe essentiel doit ensuite être respecté dans la durée. Tous les films considérés comme des chefs-d’œuvre remplissent ces deux conditions. »

Nagisa Oshima4

« Je ne saurais citer que peu de films qui rendent les notions de l’Histoire aussi complexes. Nous assistons à un savant mélange entre l’histoire et la science sociale, les chroniques issues de l’héritage du village et les légendes orales transmises de génération en génération, aussi bien que les fragments d’histoire laissés par les plus lointaines limites de l’expérience humaine. Tout ceci est rythmé par les récoltes cycliques du riz, qui a régi la vie des gens à travers les âges. Ce qui est véritablement extraordinaire concernant ce film est le concept même de l’histoire qui n’est pas la simple résurrection du passé, mais quelque chose de palpable et vivant au présent. »

Markus Nornes5

- 1Ogawa Shinsuke, cited in “Of Time and Struggle, Four films by Ogawa Productions,” occasional publication by Courtisane Festival.

- 2Courtisane Website.

- 3Abé Mark Nornes, “The Theater of a Thousand Years,” Journal of International Institute 4, Issue 2, Winter 1997.

- 4Nagisa Oshima, cité dans le communiqué de presse de « Shinsuke Ogawa & Ogawa Pro. Une rétrospective (du 03 avril au 28 avril 2018, Concorde, Paris)».

- 5Markus Nornes, cité dans le communiqué de presse de « Shinsuke Ogawa & Ogawa Pro. Une rétrospective (du 03 avril au 28 avril 2018, Concorde, Paris)».