“The following phrase, delivered during a fight on how to wipe your feet when entering somewhere, expresses the stakes of the film: “I feel like Solomon who asked God to provide him with an intelligent heart, because it’s the ultimate gift a man can receive... The human heart is the only thing in the world capable of assuming the burden of dialogue with oneself, of making living with others bearable, although they will forever be strangers to us.”

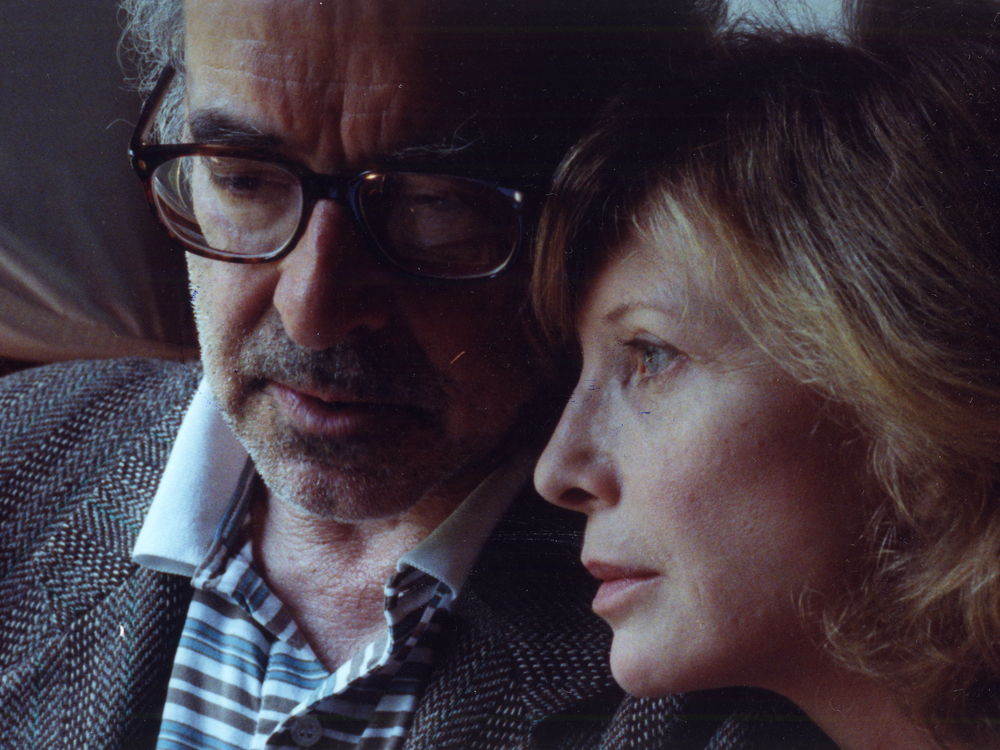

It is spoken by the dark voice of Godard, with his very beautiful, rather sinister unshaved face, expressing something somewhere between flayed suspicion and the smile of a young punk. It’s his voice expressing the ambition of her cinema, Miéville’s: “This intelligent heart has the power to penetrate the darkness, to see through the terrifying façades of the real that surrounds us... it rotates around the most intimate core only in order to catch a ray of the ever-terrible light of truth.” Which is what Nous sommes tous encore ici does, in its own disturbing way.”

Jean-Michel Frodon1

Jean-Michel Frodon: Who is this “we” in the film title?

Anne-Marie Miéville: For me, it was mostly about words. The film is essentially built around words; some of them are really old but still seem very contemporary to me. These words are all still here and we are here to say them.

Where does this central place for words come from?

From theatre. Originally, I had received a proposal from a theatre in Switzerland to direct a piece. As I couldn’t really picture myself doing an existing piece, nor writing one, I went to this composed material, and then the theatre project didn’t materialize. I wanted to turn it into a short film by rearranging the third part to take advantage of the possibilities of cinema.

[...]

These characters inevitably appear as the couple Miéville-Godard.

I know I can’t avoid it, and of course, it isn’t entirely wrong either, but it’s a very limited take on things. I make films based on what I know, but I try to pursue more general themes. It would be a pity to reduce it to a small personal affair. The third part is connected to the first two, with the concept which was central in Lou n’a pas dit non: a man and a woman is also one humanity with another humanity.

Jean-Michel Frodon2

“I don’t have any discourse on the image. I work in a very practical way. I move forward slowly. I find a cheap setting, and I spend some time there. I work on the text for a long time. I picture things. I construct the journey, the découpage, then come the ideas for shots. But I don’t have any discourse on the image. Except that I try to work with cameramen in a humble way. When they arrive in a setting, they start from what the light offers them. It is always less good when they ignore the natural light in order to then recreate it. It’s less honest.”

Anne-Marie Miéville3

“This is shown by Anne-Marie Miéville in a short introduction, by describing the words that were undoubtedly used by the jury discussing her script and the funding she was asking for. The remarks falling from their mouths are aesthetical and economical (no common thread between the parts, weak budget) and end with a statement that carries a long way, from the present towards the future: “Poetry is over!” This film bears witness to the fact that that is not true... for now.”

Freddy Buache4

“It may not seem so, but Nous sommes tous encore ici is a very cruel film. A film in three integrally embedded parts... Thus three characters. But above all, three anchored periods of time, three logical periods. First, a crucial philosophical questioning of life, justice, equality (with excerpts from Plato's Giorgias). Second, an extension of that reflection via a naked figure, tracing the contours of human horror – a development of which we will see functions as a pass door (alluding to the theatre) (with fragments from Hannah Arendt's The Origins of Totalitarianism). Third, the couple as a hypothesis of happiness: the space of love but also the place of a certain kind of work, permanent and vital. The work of love, without which there is no lasting couple.”

Olivier Seguret5

« Avec cette phrase qui dirait, au détour d’une engueulade sur la manière de s’essuyer les pieds en entrant, comme l’enjeu du film : « Je me sens comme Salomon qui demandait à Dieu de lui accorder un cœur intelligent, parce que c’est le don le plus éminent qu’un homme puisse recevoir... Le cœur humain est la seule chose au monde capable d’assumer le fardeau du dialogue avec soi-même, de nous rendre supportable le fait de vivre avec d’autres qui nous sont à jamais étrangers. »

C’est la voix sombre de Godard qui le dit, avec son visage très beau très vilain, et mal rasé, entre méfiance écorchée et sourire gamin vaurien. C’est sa voix à lui qui dit l’ambition de son cinéma à elle, Miéville : « Ce cœur intelligent a le pouvoir de pénétrer les ténèbres, de percer à jour les façades effrayantes du réel qui nous entoure... il tourne autour de ce noyau le plus intime uniquement afin de saisir un rayon de la lumière, toujours terrible, de la vérité. » Ce que fait, à sa manière déroutante, Nous sommes tous encore ici. »

Jean-Michel Frodon6

Jean-Michel Frodon : Qui est ce « nous » dans le titre du film ?

Anne-Marie Miéville : Pour moi, il s’agissait surtout des mots. Le film est construit essentiellement sur les paroles, certaines sont très anciennes mais me semblent toujours d’actualité. Ces mots sont tous encore ici et nous sommes encore là pour les dire.

D’où vient cette place centrale accordée aux mots ?

Du théâtre. À l’origine, j’avais reçu une proposition d’un théâtre en Suisse pour une mise en scène. Comme je ne me voyais pas prendre une pièce existante, ni en écrire une, je suis partie vers ce matériau composé, et puis le projet théâtral ne s’est pas concrétisé. J’ai eu envie d’en faire un petit film en remaniant la troisième partie pour profiter des possibilités du cinéma.

[...]

Ces personnages apparaîtront forcément comme le couple Miéville-Godard.

Je sais que je ne peux pas y échapper, et bien sûr, ce n’est pas entièrement faux, mais très réducteur. Je fais des films en partant de ce que je connais mais en essayant d’atteindre des thèmes plus généraux, ce serait dommage de ramener ça à une petite affaire personnelle. Cette troisième partie est liée aux deux premières, avec cette notion qui se trouvait au centre de Lou n’a pas dit non : un homme et une femme, c’est aussi une humanité avec une autre.

Jean-Michel Frodon en conversation avec Anne-Marie Miéville7

« Je n’ai pas de discours sur l’image. Je travaille de manière très pratique. J’avance à petits pas. Je trouve un décor pas cher, j’y passe du temps. Je travaille longtemps sur le texte. J’imagine. Je fais les parcours, le découpage, puis les idées de plans viennent. Mais je n’ai pas de discours sur l’image. Si ce n’est que j’essaie de travailler avec des opérateurs qui sont dans une démarche d’humilité. Lorsqu’ils arrivent sur un décor, ils partent avec ce que donne la lumière. C’est toujours moins bien quand ils font abstraction de la lumière naturelle pour la recréer. C’est moins intègre. »

Anne-Marie Miéville8

« Anne-Marie Miéville, pendant un bref avant-propos, le montre en rapportant les propos qu’échangèrent, sans doute, les juges qui, devant son scénario, discutèrent de l’appui qu’elle demandait. Les remarques tombées de leur bouche, de l’ordre de l’esthétique et de l’économie (pas de fil rouge entre les parties, la faiblesse des budgets) se terminent sur un constat qui porte loin, du présent vers l’avenir: « la poésie, c’est fini! » Ce film témoigne que ce n’est pas vrai... pour le moment. »

Freddy Buache9

« Nous sommes tous encore ici n’en a pas l’air, mais c’est un film d’une grande brutalité. Un film en trois morceaux solidairement encastrés… Trois personnages en tout et pour tout, donc. Mais surtout trois temps enchâssés, trois périodes logiques : primo, un questionnement philosophique crucial sur la vie, la justice, l’égalité (extraits du Giorgias de Platon) ; secundo, un prolongement de cette réflexion à travers une figure nue, venue tracer les contours de l’horreur humaine, prolongement dont on observera qu’il fonctionne comme un sas (le théâtre) (extraits de La Nature du totalitarisme d’Hannah Arendt) ; tertio, le couple comme hypothèse de bonheur : l’espace de l’amour mais aussi le lieu d’un certain travail, permanent et vital, ce travail de l’amour sans lequel il n’est pas de couple qui dure. »

Olivier Séguret10

- 1Jean-Michel Frodon, “Reserving the Top Spot for Words,” originally published as “Réserver la première place aux mots” in Le Monde, 20 March 1997. Translated by Sis Matthé, as published in Pas de deux. The Cinema of Anne-Marie Miéville, compiled, edited and published by Sabzian, Courtisane and CINEMATEK.

- 2Jean-Michel Frodon, ““When Godard accepted the role, I knew he wasn’t trying to put on a show”. Interview by Jean-Michel Frodon,” originally published as “« Quand Godard a accepté le rôle, j’ai su qu’il ne chercherait pas à faire un numéro ». Propos recueillis par Jean-Michel Frodon” in Le Monde, 20 March 1997. Translated by Sis Matthé, as published in Pas de deux. The Cinema of Anne-Marie Miéville, compiled, edited and published by Sabzian, Courtisane and CINEMATEK.

- 3Anne-Marie Miéville, “Barren Times. Interview by Olivier Séguret and Anne Diatkine,” originally published as “« Une période désertique ». Propos recueillis par Olivier Séguret et Anne Diatkine” in Libération, 19 March 1997. Translated by Sis Matthé, as published in Pas de deux. The Cinema of Anne-Marie Miéville, compiled, edited and published by Sabzian, Courtisane and CINEMATEK.

- 4Freddy Buache, “Non-compliance with the Prevailing Circumstances,” originally published as “Insoumission aux circonstances du moment” in Le Matin Dimanche, 6 April 1997. Translated by Sis Matthé, as published in Pas de deux. The Cinema of Anne-Marie Miéville, compiled, edited and published by Sabzian, Courtisane and CINEMATEK.

- 5Olivier Séguret, « Un amour de philo, » Libération, 19 March 1997 [Translation: Courtisane].

- 6Jean-Michel Frodon, « Réserver la première place aux mots, » Le Monde, 20 mars 1997. Ce texte est également inclus dans Pas de deux. Le cinéma de Anne-Marie Miéville, compilé, édité et publié par Sabzian, Courtisane et CINEMATEK.

- 7Jean-Michel Frodon, « « Quand Godard a accepté le rôle, j’ai su qu’il ne chercherait pas à faire un numéro ». Propos recueillis par Jean-Michel Frodon, » Le Monde, 20 mars 1997. Ce texte est également inclus dans Pas de deux. Le cinéma de Anne-Marie Miéville, compilé, édité et publié par Sabzian, Courtisane et CINEMATEK.

- 8Anne-Marie Miéville, « « Une période désertique ». Propos recueillis par Olivier Séguret et Anne Diatkine, » Libération, 19 mars 1997. Ce texte est également inclus dans Pas de deux. Le cinéma de Anne-Marie Miéville, compilé, édité et publié par Sabzian, Courtisane et CINEMATEK.

- 9Freddy Buache, « Insoumission aux circonstances du moment, » Le Matin Dimanche, 6 avril 1997. Ce texte est également inclus dans Pas de deux. Le cinéma de Anne-Marie Miéville, compilé, édité et publié par Sabzian, Courtisane et CINEMATEK.

- 10Olivier Séguret, « Un amour de philo, » Libération, 19 mars 1997.