Gildas Grimault: Many documentaries play on humour and emotion to get their message across. Why did you refuse that approach?

Gérard Mordillat: We wanted to film power. On an intellectual level, we were working along the lines laid out by Michel Foucault in his inaugural lecture at the Collège de France, ‘L’ordre du discours’. He showed how the stakes of power are measurable within the views expressed. We therefore focused solely on the employers’ words without leaving any room for emotion, the biography of the bosses, their personal and professional past. We didn’t wish to appear as their interviewers or even their contradictors. We wanted to get them to expound their theories in front of the camera while leaving them the time necessary to deepen their thoughts while using the cinema as a critical tool.Do you think it would be possible to make a similar film today?

Nicolas Philibert: With hindsight, there are probably people who will find that ‘our’ bosses were a little naïve and thereby assume that their successors would not play along so easily. But that’s far from sure! We all know that power today is wielded through communication and images. And, on that level, the bosses know the ropes. They freely show themselves, appear in the media and express their vision of the world without any complexes. That certainly wasn’t the case at the time of filming. Employers rarely appeared in public and hated doing so. Some of them were nonetheless taking courses to learn how to behave in front of a mike or a camera but they were still an exception. The bosses cultivated the art of secrecy. Of course, that secret dimension still exists today – the decisions are made in the wings – but today’s employers show a certain outspokenness whereas, back then, they displayed a great deal of restraint. Our project wasn’t so much ‘What is capitalism?’ as ‘What is capitalism ready to show of itself?’ So if we were to make the film again today, certain replies would of course be a little different but a film like this could still be made.

Gildas Grimault in conversation with Gérard Mordillat and Nicolas Philibert1

Guy Gauthier: How did you go about persuading them?

Nicolas Philibert: We didn’t conceal the fact that our film had a critical dimension in that it would subject their words to the closest scrutiny possible. All the same, there was no question of arguing with them. We met them before shooting to explain our method and prepare, with them, the themes that would be tackled: the hierarchy, relations with the unions, conflicts, strikes, the legitimacy of power in the company, etc. After filming, we invited them to see the dailies, we discussed them together and, most of the time, we offered them a second interview so that they could go further and perfect their replies.

At first, some of them probably expected us to try to trap them, to contradict them or provoke them, as journalists often do on TV. But our approach was the exact opposite. Controversy and sound bites, often very witty, were part and parcel of the terrain that they were prepared for. On the contrary, we wanted to allow them to express their thoughts fully, without any opposition. No contradiction! We created a void before them so that their words could have a free rein and so that the audience could observe, ‘in sequence’, the circumvolutions of their thoughts that were laid bare without cuts or effects. On that level, one can refer to the staging of the employers’ views, with the desire to show that these views are not only what is expressed but also what is left unsaid, the silences, attitudes, gestures, intonations, accents, hesitations, slips, etc.

Weren’t you tempted to bring in workers or union members?

Actually, at first, we did consider the idea of pitching the film between these two extremes: the bosses’ view and the union view. But we soon abandoned that idea. It would have led only to false dialectics. You get a boss to talk then you go to find a worker whom you get to say the exact opposite, you cut their two replies together and that gives the illusion of a debate: that’s the surest way to prevent people from thinking. The film’s critical dimension does not lie in a commentary or a counter-view, it comes uniquely from our cinematic choices: the framing, the fact that our questions are absent, from a few shots of the factories that punctuate the interviews, the editing and this almost fictional perspective that we have given to the film as a whole. Our approach was the opposite of the militant films that were so numerous at the time. In a militant film, you try to convince people, you seek the audience’s emotional backing. There was no question of demonizing them to make a point. No question of making them into caricatures. We wanted to make a political film, in the noblest sense: not to tell people what they should think but to make them think...

They weren’t filmed in a studio or an imposed setting...

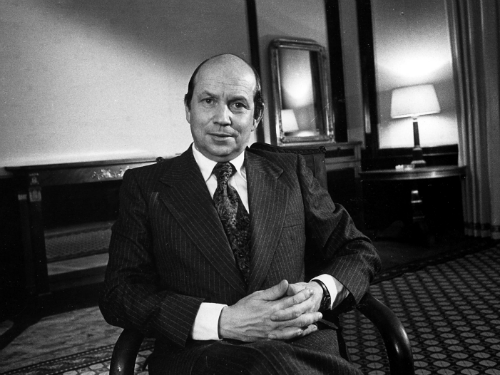

On the contrary, we left the choice of setting to them: at home, in their company, wherever they wanted... At the same time, they attempted to show the most flattering image of themselves and their company... and that ended up becoming obvious on the screen. Relatively speaking, of course, our approach may call to mind that of certain court painters, like Velasquez or Gainsborough, who spent their lives painting the powerful people of their times: princes, kings, popes, dukes... and whose commissioned portraits, staged by the models themselves, reveal the latter’s vanity.

So how did the bosses react on seeing the film?

A few weeks before the theatrical release, we invited them to a private screening. They came with their staff or their legal teams, but it all went well. They complained a little about the title that they found a little provocative but it went no further than that and the film was released without any problems. The press greeted it warmly and it had a relatively honourable career on the art-house circuit before being distributed on parallel circuits through works’ committees. In the meantime, Mordillat and I had edited the three-hour version commissioned by the INA and that was due to be broadcast on Antenne 2 in November 1978, with a one-hour programme each week. And that’s when the problems began...

Guy Gauthier in conversation with Nicolas Philibert2

- 1Gérard Mordillat and Nicolas Philibert, “His Master’s Voice (La voix de son maître),” interview by Gildas Grimault.

- 2Nicolas Philibert, “Cinema, Television, Censorship,” interview by Guy Gauthier.