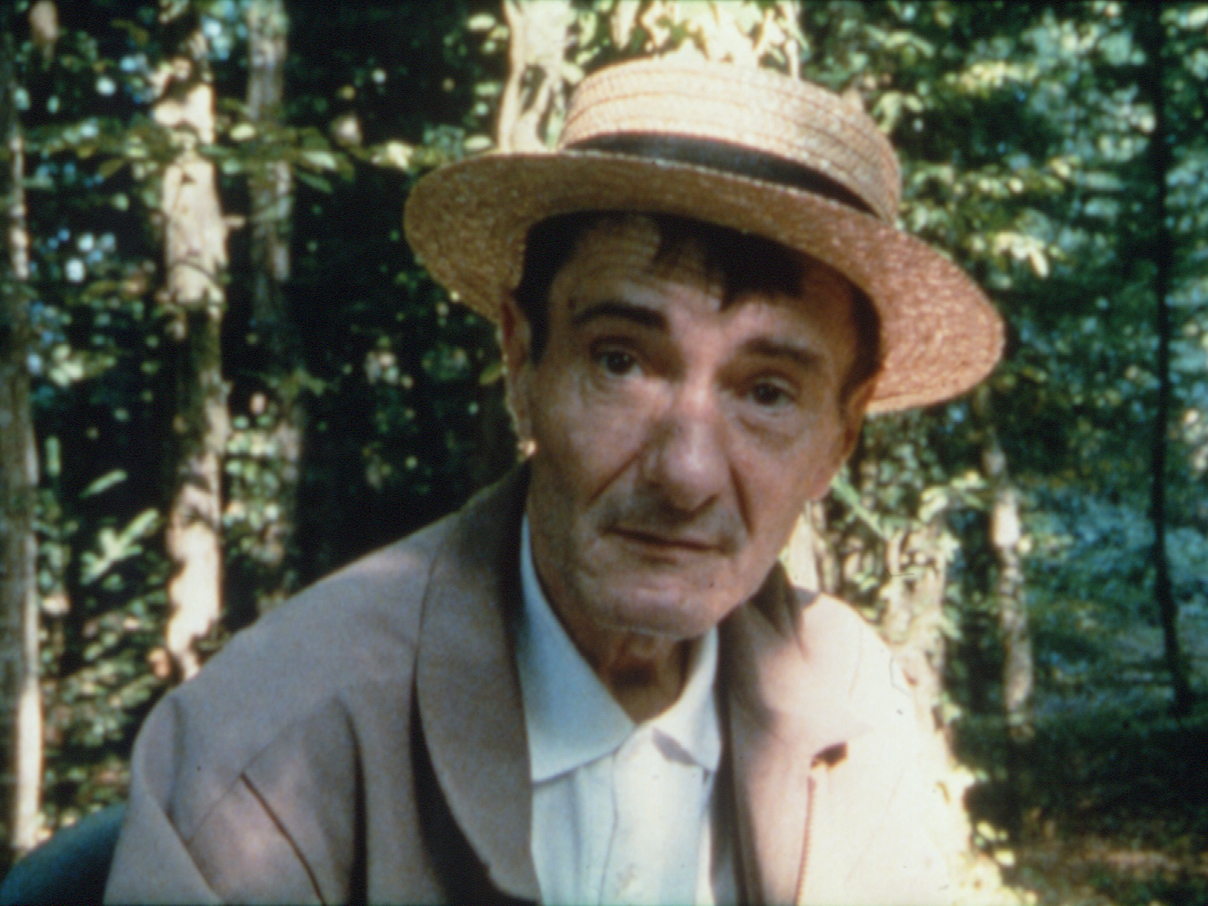

Every summer the residents and nurses at La Borde psychiatric hospital put on a play. In 1995 they performed a work by Witold Gombrowicz, who fully understood what the residents also know: that feelings can't be “crammed into words.”

Patrick Leboutte: How did the idea for the film come about?

Nicolas Philibert: Originally, several different people suggested that I should go to La Borde. I’d already heard about this institution, which is frequently – and wrongly – assimilated with the anti-psychiatric school and that nonetheless has a very special approach to madness. But up until then it had never occurred to me to make a film in the field of psychiatry and it took me some months to make my mind up. The prospect of dealing with the world of crazy people alarmed me and I couldn’t see how to make a film in a place like that without being intrusive. After all, people go there to find a little peace and quiet!

From my very first visit, however, I was struck by the atmosphere of this odd château lost in the woods: the way everybody there is welcomed and respected... It’s quite impressive to find yourself in an asylum, if only as a visitor: the suffering and distress of some of the patients are blatantly obvious! Yet there was something soothing about it, there were no walls or white coats, a very strong sense of community, and a feeling of freedom... Jean Oury, who has been running La Borde from the word go, met me and questioned me at some length about my intentions. At the time, I didn’t have any and, on the contrary, I told him about my reluctance to film mad people. How could I avoid the folkloric, picturesque aspect of madness? For what higher interest would I be peacefully and happily filming people in a situation of weakness, people who are disoriented and made vulnerable by their suffering? People who might not always be aware of the presence of the camera and even less of the impact of its images. Or others for whom the fact of being filmed might run the risk of fuelling a sense of persecution, or even bring on a state of delirium or lead to a ‘performance’ for the camera?

And then, oddly enough, during my subsequent visits, as I continued to express my reluctance, residents and staff alike started to encourage me. If I had such scruples, they said, it was a good sign... In their eyes, the questions that I was asking myself called for much more subtle answers. I shouldn’t think, certain patients said, that just because they were afflicted with psychological disorders or mental illness, they were going to let the camera use them as tools! In short, my preconceptions faded and my fears, resulting from my questions, ended up by turning into a desire to tackle them... As if this place, through the vigilance that it exerts upon itself, suddenly made possible things that would have probably been immodest elsewhere.

What were the basic choices that guided your work?

In each of my films, I look for a story or a metaphor that will enable me to ‘transcend’ reality. What is invariably involved is creating narrative based on the place I am concerned with and sidestepping that pedagogic approach of the documentary which very often limits its cinematic range in advance. So I needed to go beyond a mere description of daily life, even if that dimension is very present here. And with the theatrical adventure that was taking shape, I really landed on my feet! It was probably just a pretext, a way of getting to something more essential; but at least I had a real thread. And then the theatre offered me a chance to get close to the people there, but without intruding into their privacy. Last of all, the theatre would allow me to give the film a light touch and even a certain gaiety, and I thought that was very important. Of course, the play has a lot to do with that!

[...]

At the beginning of the film, with the figures wandering through the grounds, we’re not far from stereotypes...

It’s true that you might feel like a ‘voyeur’: the characters are filmed ‘at a distance’, in their loneliness; they are strangers to us, just as we are to them. From that moment on, all the clichés to do with madness spring to mind. But the film outlines a trajectory. Little by little, we get closer to them, an encounter occurs and the clichés become blurred and give way to actual people. I’m aware that these opening shots may seem aggressive or violent but the only way to go beyond stereotypes was to confront them from the outset.

These same shots return at the very end...

They’re similar shots, true, but I think we see them with a totally different emotion because, in between time, the characters have become closer to us. The fact of returning to what we saw at the beginning allows us to show the distance covered.

[...]

To sum up, how would you define the subject of your film?

Ever since this interview started, I have been talking about the relationship with the people I filmed, and that is no coincidence – I believe that is the actual subject of the film. A film about madness? Definitely not. About psychiatry? Even less. About theatre? A pretext... Rather than making a film about, I’ve made a film with and thanks to: with ‘crazy people’ and thanks to La Borde. So if I really had to put my finger on the subject, I would say that it’s a film that talks to us about what connects us to the other; a film about our ability – or inability – to make a place for the other. And, last of all, it is a film about what the other, in all his or her strangeness, can reveal to us about ourselves.

Patrick Leboutte in conversation with Nicolas Philibert1

- 1Nicolas Philibert, “How to Avoid the Folkloric, Picturesque Aspect of Madness?,” interview by Patrick Leboutte.