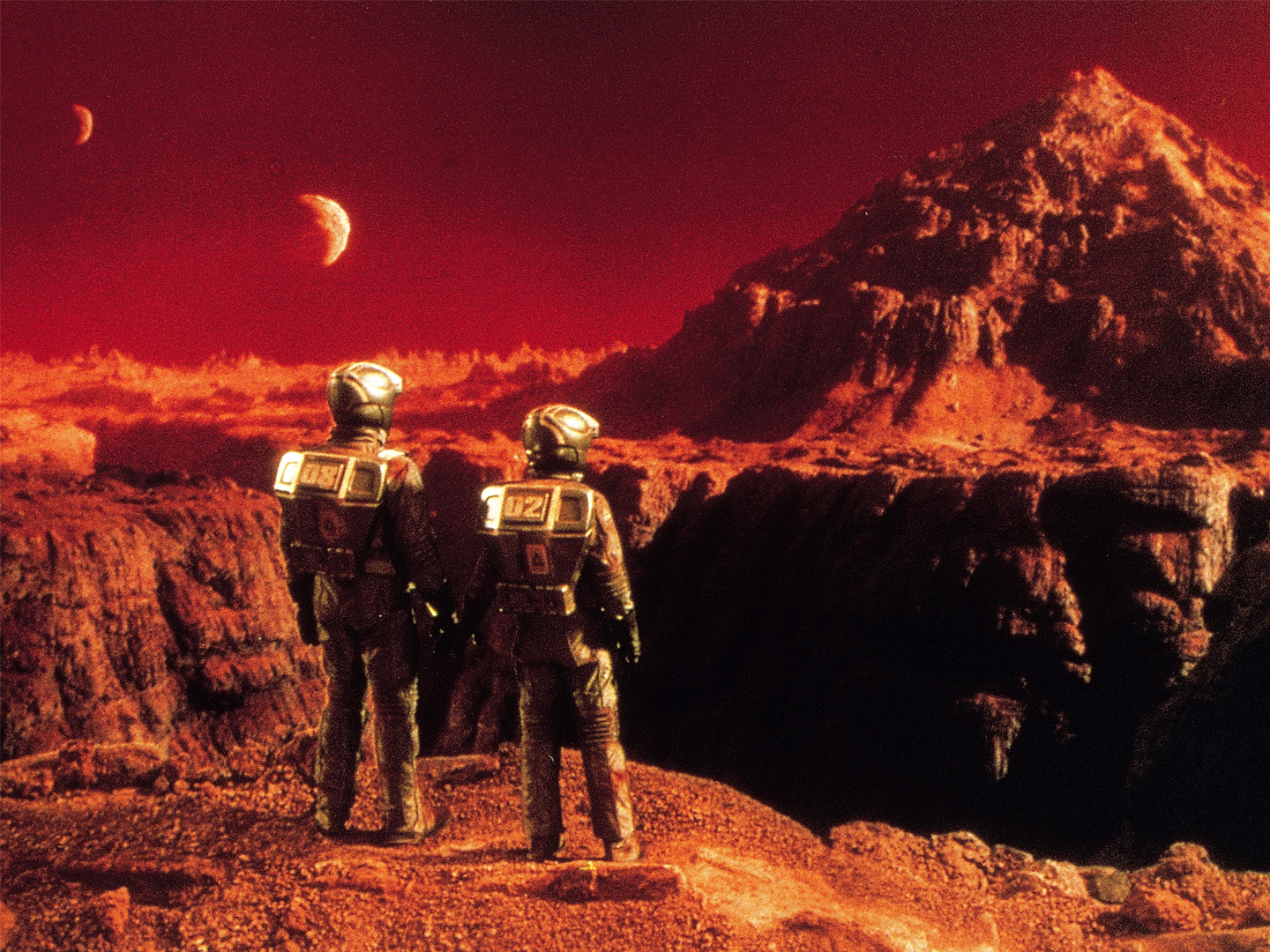

When a man goes in to have virtual vacation memories of the planet Mars implanted in his mind, an unexpected and harrowing series of events forces him to go to the planet for real - or is he?

“For the director Paul Verhoeven, Total Recall was the next step in his own improbable colonization of Hollywood, following RoboCop three years earlier. Verhoeven had already established himself in his native Holland as a craftsman and provocateur of the first order, eager to test the extremes of sexuality and violence – his first English-language film was appropriately titled Flesh + Blood – and indulge a fetish for Hitchcockian blondes and mankind’s darkest impulses. As a small child, Verhoeven had lived through the Nazi occupation and the experience shaped him, not only in films that would address the war directly, like Soldier of Orange and Black Book, but in genre entertainments that smuggled themes about life under fascism.”

Scott Tobias

“Schwarzenegger, eind jaren tachtig een wereldster, wilde na het zien van Verhoevens Hollywooddoorbraak Robocop (1987) per se met de Hollandse regisseur werken, en zo gebeurde. Met een budget van ruim vijftig miljoen dollar – indertijd een duizelingwekkend bedrag – tuigde Verhoeven op basis van een kort verhaal van Philip K. Dick (We can remember it for your wholesale, 1966) een fascinerende, toekomstige wereld op. Een wereld waarin je je continu afvraagt wat feit en fictie is, waan en werkelijkheid, en die perfect aansluit bij onze wereld van feiten en fabels, en van ‘fake news’.”

Belinda van de Graaf

“De film balanceert voortdurend op de grens tussen feit en fictie”, legt Verhoeven uit. “Is Doug het slachtoffer van een groot complot of beeldt hij zich alles in en staat hij op de rand van een psychose?” Dat gegeven van verschillende werkelijkheden waar de held uit moet kiezen werd later gemeengoed in Hollywood, bijvoorbeeld in The Matrix. Maar in 1990 was dat soort plots nieuw. In mijn hoofd zag ik overeenkomsten met Rashomon van Kurosawa, alleen worden daarin verschillende realiteiten na elkaar verteld.”

Paul Verhoeven in conversation with Robbert Blokland

"There's a long story to Total Recall. The first script was written in '79 by Ron Shusett and Dan O'Bannon, the writers of the first Alien, and then in the ten years that passed between the first draft and when I started to work in the movie, which was '88 or something, they wrote together with some other writers twenty-five drafts of the same screenplay. There were seven directors involved, and I think several producers and co-producers, and they started the movie several times, and it always fell apart. And so when I got the script I had twenty-five drafts to go through and to select from - then filming you found out that first of all you have to select out what you've got for Arnold. There was never an Arnold Schwarzenegger role in the movie - it was about a normal guy, physically, I mean. Arnold is very normal, but he has the kind of physique that is bigger than life, isn't it? But this was written for somebody who looks like Woody Allen, somebody like that, and so we had to rewrite the script completely, and alter the third act completely."

Paul Verhoeven in conversation with Chris Shea and Wade Jennings

“Working with Arnold [Schwarzenegger] was the most pleasant part of the whole production. Arnold is such a supportive guy, and he's so concerned with getting the best. He has a very pleasant temperament, always very balanced and always in a good mood... and that is in contrast with the whole production, which was very difficult. I'm not even talking about his acting, I'm talking about him as a human being. His social abilities formed a support system which was probably the most pleasant aspect of the whole movie. I've never met an actor that is so easy to work with and is smart, makes good judgments, and is so supportive of the director.”

Paul Verhoeven in conversation with Bill Florence

“For me... to be honest, the war was a great time. I mean I was a child and I loved it. (...) It was like every day was a big adventure. Of course if your brothers and sisters and parents are killed, that's a different situation, but in my family nobody was killed. So as a child you don't look much further around you - you're not aware of the 100.000 Jewish people who are sent away and never come back - you realize that after the war, but during the war I never realized it. For me, it was like the most fantastic special effects you've ever seen. Every night when you look up at the sky you would see burning planes coming down. (...) These things were so strange, in fact, but so normal for me at the time that I think that's responsible for a lot of the violence in my movies, my feeling that violence is normal, and that peace is a-normal, that war is the natural state, and that peace is an a-natural state- which of course is not true, and of course I'm not making propaganda for war - to the contrary.”

Paul Verhoeven in conversation with Chris Shea and Wade Jennings

“Those looking for a good time in a dystopic, totalitarian colony can still find it.”

Scott Tobias