Documenting and Telling the Torments of the World

Interview with Jocelyne Saab

This text is a retranscription of several interviews conducted in Paris between 2010 and 2013. Jocelyne Saab took part in the game of questions and answers with great honesty, kindness, seriousness, and even patience, given the fact that the interviews lasted several hours each time. I would like to take this opportunity to thank her as well as Nicole Brenez (for the beautiful retrospective at the Cinémathèque française in the spring of 2012) and Aliette Guibert (for hosting a first version of this text on criticalsecret).

First Steps of a Filmmaker-Reporter

Olivier Hadouchi: How did your career as a filmmaker begin?

Jocelyne Saab: Actually, I didn’t study film, nor did I follow the classic path of a filmmaker. In my family, in the society of the time and the milieu I lived in, film wasn’t considered a serious endeavour, unlike law or economics, for example. So I agreed to study economics, knowing that it was a way of buying time, until I was ready to follow my own path and go into journalism and film.

What were your first films? They were film reports, weren’t they?

Indeed, I began by making film reports, documentaries, and I didn’t come to fiction until much later. The boundaries between the two aren’t very clear-cut, however, and there are often documentary elements in fiction films and vice versa. At the time, there was a fabulous reporting tradition, with film crews in conflict zones that didn’t hesitate to take risks and demonstrate a certain situation by bringing us the footage. Resorting to cinema, especially to documentaries, in order to provoke or accompany social change, to denounce or to provide a basis for action, all this was very much present when I started. The effervescence of the 1960s continued to shake a large part of the world’s youth. So, no doubt with the energy and perhaps even the recklessness of youth, I found myself covering wars with very important consequences on a regional as well as a global scale. Think of the October War in 1973, of the Palestinian situation, because the PLO had fled to Lebanon after the problems in Jordan, or of the war in Lebanon which broke out in 1975 and would last for too many years; and I met political leaders like Yasser Arafat, Houari Boumediene or Colonel Gaddafi.

One of these works is The Suicide Commandos, which will be broadcast on television under the title The Rejection Front.

Of course, in retrospect, we could say that the whole thing is edited in a rather classic way: you take a few images, add an interview, then some more images, a new interview... Yet, it still has a certain value, even in retrospect, because it shows a reality that would gradually become more widespread: the suicide commandos. Often young men, ready to die as martyrs for a cause after being recruited by party or movement leaders. The floor is given to leaders such as Nayef Hawatmeh of the DFLP [Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine] and Ahmad Jibril of the PFLP-CG [Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - General Command], who is filmed from behind, without showing his face. We see the shock troops practicing. But you’ll notice that I decided to keep a scene that may seem unexpected and surprising in this context: one of the commando members is dancing, rhythmically shaking his hips, a scarf tied around his waist. His moves are very feminine, I think. Let’s not forget that dancing accompanies all the important acts of life. At the time, they made me promise not to reveal the location of this secret base. And this scoop brought about a lot of jealousy from my colleagues, as well as reprimands and criticism from the more moderate division of Fatah and the PLO.

Intrigued journalists wondered how a young woman, a virtually unknown debutante, had managed to record images of suicide commandos?

Not to mention the problems I had afterwards in France because of this film... When I applied for the French nationality, I was entitled to a long interrogation by the counter-espionage services. I asked them: why don’t you go and see the other French journalists who also met with the suicide commandos, five or six months after me? I had just done my job as a journalist, trying to do it as well as I could. That’s why I gave a voice to the militant division of the Palestinians, who were at that time united in the Rejectionist Front. This didn’t necessarily mean that I supported either position. I was a journalist and gave the floor to everyone.

What was the criticism from PLO members?

The members of Fatah reproached me for interviewing the militant division of the resistance movement, in short, for providing a negative image of the Palestinian struggle by showing its most radical and violent fringe group. “Don’t you see that they extend their arms and that it looks like a Nazi salute. In the West, they’ll equate those who fight for a Palestinian state with anti-Semites or pro-Nazis, and you very well know that’s not the case...” Were they performing a Nazi salute? In retrospect, I don’t think so, but there may have been a possibility of misunderstanding. In the Lebanon where I grew up, a truly cosmopolitan country, open to multiple faiths and granting rights to religious minorities, there was no anti-Semitism in society. Following the various conflicts with the State of Israel and all the bombings, they started criticizing the country, a criticism that was often virulent given the extent of the human and material damage, but I think it is important to separate the two and recall the absence of any anti-Semitic tradition in Lebanon or in the neighbouring countries, whereas it was once widespread in Europe or Russia. Anti-Semitism is really something I discovered in France and was not part of my personal experience in Lebanon.

To come back to the film, in my next works I introduced and interviewed the leaders of other movements, starting with Yasser Arafat himself in 1973 – he didn’t give many interviews at the time, so it was important – not to mention the Palestinian population, women, the inhabitants of the refugee camps in the south of Lebanon or on the outskirts of the capital. Did I try to make up for it by giving the floor to Yasser Arafat or Fatah in documentaries? Again, just because I listened to such and such member of the Rejectionist Front doesn’t mean that I adopted their point of view. Suicide commandos were something new at the time, a practice that has unfortunately become widespread in the Middle East and elsewhere afterwards. All these reprimands and discussions allowed me to grow artistically and to always reflect on what I was filming: why and for what purpose is an image made? What should be shown and presented? Not for censorship, self-censorship or propaganda reasons. All this provoked in me a useful and necessary reflection on cinema, on the meaning of images and their reception.

At the Heart of Lebanon in a Whirlwind

As soon as the war in Lebanon began, in 1975, you returned and decided to focus on what was happening there?

Indeed, war correspondents were then present in several places in Asia and the Middle East. Eric Rouleau, Ania Francos, Jean Lacouture, Lucien Bodard – and many more – all passed through Beirut in the 1970s, notably because the PLO headquarters were located in Lebanon at the time, because the Cyprus dispute had just broken out and was still going on, and because Lebanon was freer than other Arab countries. When the war started, press correspondents, photographers and reporters arrived in large numbers (Raymond Depardon, the American Jon Randal...). They inspired me, and I told myself that I had to understand what was happening in my country, because I very quickly had the intuition that it wouldn’t be a short war and that its consequences would be dramatic. However, I had already become very politicized, educated by the 1969 demonstrations in Lebanon, Black September in Jordan, the Vietnam War, the Palestinian question in general, and the division of Cyprus.

What surprises me when I rewatch Lebanon in a Whirlwind is the reserve it expresses towards each of its protagonists. The film isn’t dogmatic, even if one feels that it probably expresses more sympathy for the left than for the conservative right and the Phalangists. Where does this reserve come from, at a time when the country is going to war amidst a radicalization of discourses and strategies?

It might have to do with my personal background (studies in Paris) and my partner for this film, the Swiss journalist Jörg Stocklin, that I was able to keep a certain distance and benefit from a genuine reserve towards my own country. A strange history, in a way, not to mention Jörg’s private life... Even though he was working in Beirut, he still had an outside perspective, that of a foreigner who sometimes sees things you don’t notice when you’re part of society, when you have grown up inside the country. Jörg was left-wing, and he supported the progressive camp in the conflict, but he always kept his critical spirit, devoid of any naivety. In short, he had a certain distance when analyzing the situation, and he managed to instil it in me. Perhaps I should also mention my father, who always kept his distance in the face of events and never succumbed to the ideological sirens of either side, nor advocated the exclusion of the other. The Phalangist discourse had no hold over him; he stood on his own, thought for himself, and needed no one to tell him what to do, what to think.

In the film, a great deal of attention is paid to social issues. It feels like a survey of several parts of the country, several neighbourhoods of the same city (Beirut, Tripoli). Even the former minister attending a dinner feast with wealthy friends and jewellery-covered women seems to be aware of the risk of an explosion.

The problem is that social issues have dissolved into religious disputes, which have taken precedence over everything else. But it seemed to us, at the time, that social issues were very important. In Egypt, when I shot Egypt, City of the Dead, I was also very sensitive to social issues, to the arrogant wealth existing alongside the harshest, most unbearable poverty. It’s the policy of openness and unbridled liberalization that has brought Egypt both globalization and the economic crisis from which it still hasn’t recovered.

In Lebanon in a Whirlwind, you also show the absurdity and the pathetic side of these men with their great resounding declarations.

You’ll notice that I always resort to irony and distance towards interviewees and political leaders. And I systematically show the pathetic or even totally ridiculous side of every side, of every statement by every political leader, in their way of moving towards armed conflict with such a lack of concern. In retrospect, we know the conflict has been very long and very hard for Lebanon and the Palestinians, and I think the film clearly shows the process of war, this going into battle without really caring about the consequences. The price to be paid has been very high indeed. But you’ll notice that in Lebanon in a Whirlwind, everyone is on parade. The Lebanon of today is still like that. Everybody loves to be on parade, strutting around, showing off. Why is that? It was already very present in Lebanon in a Whirlwind and it might even be worse today.

Unlike the other leaders, Kamal Jumblatt is filmed alone in his palace.

At the time, I was asked: why do you film all the political or religious leaders with their partisans except him? Kamal Jumblatt had the calibre of a modern and progressive leader. After all, he was the leader of the left-wing alliance. So he represented something important to us, and he was open-minded. He often went to India, stayed in ashrams and then came back... He radiated a great spirituality, which gave us hope. We wondered: who is this man reflecting on the state of the world? He represented something really important. Having said that, he still had armed men at home, a militia like all the others, but that was not the aspect that interested me. As for the other political leaders, I sometimes gave instructions, choosing the context in which I wanted to interview and film them with their troops. For example, the leader of the Phalangists, Pierre Gemayel, I told him: “I want to film you at the meeting table, with your supporters.” Since I was kind of in their bad books and couldn’t get permission, I called in my father so that I could film them. Actually, I was faced with a series of filming problems: a group of militia women ruthlessly questioned me, I received threats, and they tried to confiscate my camera and filming equipment after assaulting me and pulling out my hair.

In the film, you interview two other leaders of the left: Ghassan Fawaz and Fawwaz Traboulsi. Could you tell us about them?

After being an active member of the left-wing movement COAL [Communist Action Organization in Lebanon], as we see in the film, Fawwaz Traboulsi1 has become an important political thinker and is preparing a new essay on the theme of violence and memory, which I would like to discuss with him again soon. His concerns have aspects in common with mine. As for Ghassan Fawaz, he was a communist at the time, we were neighbours. In what used to be West Beirut, we lived on the first hill of independence, which was mixed, and its extension was called the Zarif neighbourhood (literally “the sand of Zarif”). Then, as the situation continued to deteriorate, with no real way out and no real victories, the country became more and more unliveable. And around 1976-1977, they left. Ghassan became a publisher in France. He wrote two pretty successful novels at the end of the 1990s, published by Seuil2 . And Fawwaz published essays and articles of political analysis. I didn’t have to travel far to film them. They lived close to my parents, so I just had to cross a few streets. In fact, looking back, I think that when I went to film the combatants in the street I had no idea... we had no idea, we were unable to predict where the violence might lead.

As for Farouk Mokkadem, he is defined as a libertarian, but he seems to consider himself more as a kind of Lebanese Che Guevara.

It’s funny that you find him sympathetic, but he really had a completely megalomaniac side. Remember when he evoked the people’s uprising against the oppression in the castle...? Don’t forget that ideologies travelled a lot in the 1960s. And in this little country, because of the very mess we were in, we could apply any ideology, but only across a tiny territory. Besides, that was true for all combatants. For example, Fawwaz Traboulsi and his COAL comrades exercised their authority on a few streets, across a tiny territory... In fact, they and other friends wanted to blow it all up. By this I mean blowing up the traditional system and replacing it with a modern, secular system. Me too, even though, unlike them, I never took up arms. Besides, in 1975, I personally believed that we were going to win, that the Lebanese left was going to win and overthrow the conservative Christian right. Because this Phalangist kind of right, this “isolationist” right – as it was called at the time – an ally of Israel in the midst of minoritarian complexity, was dragging the country towards war, preventing it from moving towards modernity, towards a system that was both socialist and truly democratic.

When thinking of recent events, of the fact that the protest movement for change in Tunisia began with the self-immolation of a young fruit seller who had his wares confiscated, I remembered a sequence from Lebanon in a Whirlwind: the passage concerning Farouk Mokkadem and the October 24th Movement in Tripoli. When Mokkadem recounts that the wares of the vendors in the city of Tripoli had been confiscated by the authorities, he adds: “We went to see these gentlemen in power.” We asked them why the wares of the vendors had been confiscated... They told us: to keep the city centre beautiful. We told them: so, abolish poverty. We were born poor; it’s not our fault. We warned them: we are going to resort to weapons. We took back the confiscated wares and gave everything back to the fruit and vegetable vendors, and we armed the vendors, who could continue their activity.” At the time, rifles were used in various types of struggles, this situation has changed. Yet, in Lebanon in a Whirlwind, as in the country at the time, was there ever a movement of democratization comparable to the one shaking the Arab world at the moment, with a desire for social change?

In Lebanon of the 1960s and 1970s, there was a deep aspiration for social change, with a view to a profound transformation. This movement was crushed around 1976-77. But I am closely following the current events related to the Arab Spring, in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya or Syria... and I support the movement for change, but I am waiting to see who is pulling the strings and what interests are at stake.

Have you ever thought of shooting a 2011 version of Lebanon in a Whirlwind?

I would most certainly be killed if I shot the equivalent of Lebanon in a Whirlwind today. At the time, the participants displayed a certain innocence, which is not at all the case today – the situation seems even more opaque. Unfortunately, there are still many weapons in Lebanon, and I am sure that at the first opportunity many people are ready to take them out and use them. It’s a country where people tense up. And this is the negative other side of all this plurality: everyone feels that they have a mission to be the one who guarantees their community, which must be defended at all costs. This can take on terrifying proportions. Not only does it produce true social conservatism, but the people that believe they have a mission act on their own and demand that other members of the community submit to the cause. Thirty-five years later, alas, I think the film hasn’t aged a bit.

At the time, Lebanon in a Whirlwind was shown in theatres in Paris together with the short film New Crusader in Orient. But no television station agreed to broadcast it?

Given the special ties between Lebanon and France, it was refused by French television because it was disturbing. They considered it too critical of the Christian and fascistic right. On the other hand, it was broadcast on television channels all over the world.

However, it concerns one country, Algeria, which is trying to play a role on the global stage by arguing in favour of a new world order, more favourable to the interests of the South...

In the mid-1970s, Algeria was very interested in what was happening in Lebanon, especially because the PLO was based in Beirut and the Palestinian question was the central concern in the Arab world. I remember that some of the senior leaders of the National Liberation Front started to wonder whether Algeria was going to experience the same kind of civil war as the one setting fire to Lebanon. I was invited by Boudjema Karèche and Yazid Khodja to present my documentaries at the cinematheque of Algiers, which was then a hotspot for global cinephilia, in front of a room full of Algerian officials – I think even the President of the Republic, Houari Boumediene, was there. The Institute of Algerian Cinema and Television bought several of my documentaries, and I had very interesting discussions with Algerian filmmakers like Farouk Beloufa, who discovered Lebanon through my films. Shortly afterwards, he would film Nahla (1979), which many Algerian critics consider one of the best Algerian films, and gave a role to Lina Tabbara, whom I filmed twice (in a film report and in Letter from Beirut). I passed on many personal contacts to him. Farouk was fascinated by the freedom of movement and the proliferation of ideas and political parties. He worked on his scenario with Rachid Boudjedra and used my documentaries, from Lebanon in a Whirlwind to Letter from Beirut, to learn about the Lebanese situation. I’m not saying that I’m the one behind Nahla, just that the film somehow interacts with my work in certain aspects. Otherwise, it’s a film in which Farouk reflects on a given situation, thinks about several aspects of it. They are his personal reflections. He was fascinated by the freedom of speech and movement in the Lebanon of the 1970s, by the multiplicity of political orientations. By the way, I filmed a making-of of Nahla, Farouk Beloufa should still have the reels somewhere. What’s interesting in retrospect is that the Algerian Film Office acquired my film Beirut, Never Again, shot on 16mm. They decided to blow it up to 35 mm and distributed it in cinemas all over the country.

Did you quickly realize that the left and the so-called progressive camp would fail?

When Kamal Jumblatt was assassinated in March 1977, we all understood that it was over. I left to make a film in Egypt and then to Western Sahara, in the same year. But I continued to live in Lebanon, even if I was sometimes away. When the Lebanese capital was besieged by the Israelis in 1982, I was there with my camera. And I didn’t leave Lebanon until 1985, when I was sick of the violence. Since then, I’ve been going back regularly.

How did your collaboration with the poet Etel Adnan for Beirut, Never Again come about? She also appears in Letter from Beirut, filmed two years later, doesn’t she?

Etel is a poet and a talented painter. She’s also the author of a major text on the war in Lebanon, a novel called Sitt Marie Rose.3 I’ve read a lot of books on the conflict, and I think it’s the best, the most accurate one. The poetic texts of Beirut, Never Again and Letter from Beirut were written in one go, she told me recently. She saw the edited images only once before she started writing. Since I recently asked her to recall all this, I prefer to let her speak. “I liked these instinctive images. I linked them to a poetic text with the same source.

You were the first to go into the street, to record these images without anyone asking you. You knew you had to do it, and you did it, you didn’t hesitate for a second. All I could do was follow you. For my part, I had instinctively understood everything you were showing. I was very sensitive to the children who had understood before us that nothing and no one would be the same again, that a period had just ended and that they would never be the same again. It was so strong that I had no choice but to pay tribute to their lucidity.” And, a little before that, you had just shot another documentary, which was called Children of War...

After Lebanon in a Whirlwind, I had a camera and a car at my disposal, and I had my house. It’s true that I didn’t have any money problems, but I didn’t have a lot. And so I took the director of photography aside and told him: come on, let’s go! Because I’d spent the night talking to journalists who’d just come back from Karantina (the refugee camp that’d just been taken over by the Phalangists), and I’d seen the end of the massacre. Plus, I’d even learnt that a friend of mine, no doubt influenced by her entourage, had enjoyed filming it from the side of the killers. She suffered a lot afterwards, for other reasons. When the settlement was stormed, many adults were shot dead in cold blood. And once the refugee camp was conquered, the attackers opened the champagne, right next to the corpses. Some children survived. When they came out at night, I had no lights or anything, but I followed the children’s route to find out where they were going because they could no longer go to the Karantina settlement, as it had just been razed to the ground and their parents had been executed. I saw they were going to the cottages on the chic beaches of the city, Saint Simon, Saint Michel, which had become settlements that still exist today. So I bought paper and coloured pencils and went to meet them the next day. While calling my TV cameraman, Hassan, who works with me, I tell them: I’m coming to film you on Sunday, you’ll show me your children’s games. They were playing war on the beach, but it quickly became very violent, so much so that I had to tell them to stop and had to take two of them to the hospital to get stitched up, because they were injured. Then we returned. And that was the most powerful moment. They were a little sheepish, because three of them had been injured, but it was as if they were bringing out the surrounding violence they had taken in and accumulated inside of them – remember, they had just witnessed a massacre. I found them among the cottages arranged as if in a chic little village, and I suggested they keep going. And then, the children, wounded and traumatized by what had just happened, broke free and mimed the massacre. And I filmed it. I carefully guarded my boxes of film, and I took the first plane to Paris, rushed to the television studios. That’s how we did it at the time: either we developed the film on the sly through friends there, or we followed the traditional procedure, which is what I did that time. I knew the footage was strong. I went to see my chief editor (Jean-Marie Cavada) and told him: “Develop the 16mm film, watch the images, and if you like it I’ll edit the film.” They developed it, couldn’t believe what they were seeing, and gave me a TV editor. Along the way, reporters came into the editing room and asked me if I had directed the children. How could I have done that? So, when the film was edited – at the time we didn’t have complete control over the montage – they asked me to add a text, which I did. Then I made a name for myself. And for Beirut, Never Again, I had the freedom to make the film entirely as I wanted.

Thirty years later, I re-used the images of the war children for my installation in Singapore. The film has toured the world, has been screened in numerous festivals, won awards, even UNICEF showed it, and NBC bought it from me a year later... For my installation, I re-edited the film in order to project it on three screens, accelerating certain passages so that the viewer is immersed in the war itself. Once again, it was all about the approach. Besides, that’s the major question of documentary film: how to approach people.

From 1975 on, you were living the war on a daily basis?

While shooting my documentary The Rejection Front, about the first suicide commandos, I met young people between the ages of fifteen and seventeen who wanted to offer their lives for the cause of their people. Deprived of everything, without a home, without dreams or plans for the future other than to live their lives in a tent, they find meaning in their commitment. I had spent the evening with them in their underground bases dug out of rock. I had seen and heard them sing, dance and shake their hips. The revolution borrowed its songs from folklore. After the ceremony, some young volunteers came up to me, and one of them asked me if I could give him my Ray Ban glasses. I replied, “It’s a birthday present. I can’t give them to you,” a little ashamed of my lack of generosity. Three years later, I was shooting Beirut, Never Again. Every morning between 6am and 10am, when the fights were less intense, I crossed a fighter wearing a pair of Ray Ban glasses. He called me by my first name and told me that he and his group had a day off in Beirut after taking the oath. During his passage in the capital, he bought a pair of Ray Ban glasses. Then, he was supposed to take part in a special operation with his group but one of them cracked and the project did not materialize. The meeting was surreal. Two days later, I went back to the same place and looked for the Ray Ban fighter on that same barricade: his comrades told me that a shell had torn his head off. That’s an example of daily life during the war.

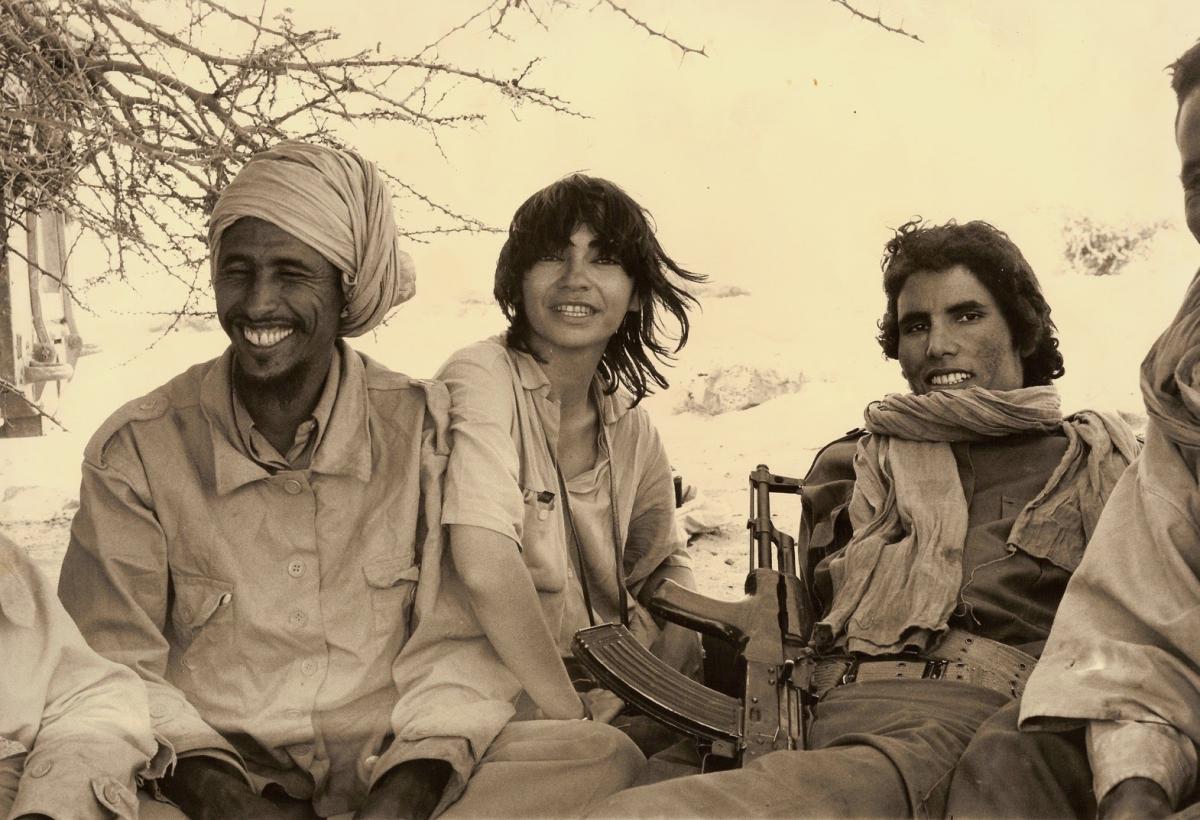

Sahara Is Not For Sale

In 1977, you travelled around a new conflict zone for Sahara Is Not for Sale. Spain withdrew from its former colony between Mauritania and Morocco. Morocco considered Western Sahara to be an integral part of the country, while a movement supported by Algeria (the Polisario Front), claimed the independence of the territory, asserting that the Saharawis are not Moroccan.

Several critics at the time highlighted the film’s concern for objectivity, and it was screened at the UN during a session devoted to this issue. Honestly, I did not try to subscribe to either thesis on Western Sahara. The funny or the most surprising thing is that both countries indirectly participated in the financing of the documentary. Both criticized me. The Algerians did not appreciate the fact that I showed archival footage containing a statement by their president Houari Boumediene. But I had bought these images, and it seemed normal to show them because the Algerians were involved in the conflict and supported the Polisario Front. On the other hand, Morocco was very angry with me for not subscribing to their point of view on the issue... Basically, I felt sympathy for the Saharawis, the inhabitants of the desert, and I have always been fascinated by the desert; I made the film for them, not on behalf of this or that State.

The Experience as an Assistant Director for Circle of Deceit

In 1980, you were the assistant director of Volker Schlöndorff ’s Circle of Deceit. Was it an interesting experience?

The film was sharply criticized, and I must say I have mixed feelings about it. I learned a lot from the contact with the fiction film crew, which was made up of many people. The funny thing is that in a television programme called Filming the War (with a cast including Raymond Depardon, Volker Schlöndorff, Roger Pic, Michel Honorin, Jonathan Randal, Freddie Eytan, Samuel Fuller, and myself), I was asked if my documentaries weren’t more interesting and closer to reality than Volker’s film Circle of Deceit. At the time, I didn’t have the necessary distance and thought it wasn’t up to me to answer that question. They are, without a doubt, much more relevant. Armed with your experience as a reporter, didn’t you try to intervene more in the filming of Circle of Deceit, so as to fix a more precise target?

Volker Schlöndorff was at the height of his fame at that time. He had won the Palme d’Or for The Tin Drum in 1979, and I was a young director without any experience in fiction. In 1980, he shot Circle of Deceit in Beirut. He opted for a classical structure and probably lost himself in the theme of the executioner and the victim and in a conflict whose complexity he couldn’t quite perceive because he had a starting point inspired by Camus. Today, it remains an important account of the war. Isn’t coming to film in Beirut during a war in itself an act of resistance against what is called “The War”?

From the Siege of Beirut to The Boat of Exile

Beirut, My City is an important film for you, isn’t it?

I consider it my most important film, the one I care about the most. In 1982, my house burned down. That was certainly something. It was a very old house. 150 years of history going up in flames and disappearing. All of it is suddenly wiped out. The family home wiped off the map, off the city, turned into a pile of ruins.

The war affects your own family once again?

Completely. I was going to talk about it in a film afterwards, but I needed a minimum hindsight of six months to be able to make the film. Then they said to me: “Why are you offering the images of your burned house to a rival television station?” (France 3) They only saw the rivalry, which I had to digest first.

In Beirut, My City, certain scenes reminded me of the terrible images of the bombings of Madrid or Barcelona during the Spanish War. Bombings that affected civilians, sparing no one, not even children. The scene with the emaciated children is really very hard, it looks like total desolation.

During the siege of Beirut, we knew that no one was able to reach a school for handicapped children near the camps of Sabra and Chatila. The city was under constant bombardment by the Israeli occupation army. We talked about it among ourselves every day and wondered if the children were still alive. The area they were in was inaccessible, and it took several days for the Red Cross to get a safe corridor and stop the bombing to reach this children’s school. This was one of our daily concerns, and it was very close to our hearts, because we told ourselves, “if the children are alive, we will stay alive as well”, and it gave us strength. When the news of the evacuation of the children came, it was as if we had won a victory. When I heard that they were going to be transferred to a school near my family’s house, which had burned down – and which you can see at the beginning of the film – I went back there with my camera, even though the area was still dangerous. They had been transferred by ambulance to the Armenian school in Honentmen. We risked our lives every day during the siege of Beirut, because the city was bombed non-stop. It was strange, but this risk of death from above was almost something abstract for us. In fact, we considered it a danger to be braved. The skinny (and handicapped) children I filmed were like images of death coming closer to us, to me. At the same time, capturing that image was a way of killing or taming death. Of turning it into an image-as-proof, of saving myself from my own possible death. I knew that with my job as a war reporter I could be killed. Yet, when I was filming and had my eye hidden by the camera, I always thought I was invincible.

What did daily life look like under the bombs of the 1982 siege, when you filmed Beirut, My City?

Going out as soon as the planes had passed, to film, to bear witness. Buying boxes of (La Vache qui rit-style) Picon cheese, finding gas and water. Sometimes going for dinner in the two or three restaurants that were still open, a matter of giving ourselves the impression that we were still leading a “normal” life. Saving people, filming, finding something to hold on to, keeping up to date, making sure the others are still alive. I had my car, so I went to the Palestinian headquarters every day to keep up with the situation. In the city, only the poor were left, and they hardly had anything to eat. As for our group: we were about fifty artists and intellectuals at the most. When one of us died, half of our group left.

What exactly happened?

One of us was murdered. We were leaving a restaurant, and a car pulled up in front of us. Some men came out and our friend was killed by a machine-gun blast at close range. He distributed water all over the besieged city.

Despite the constant bombing, you still went out?

We went out at night. We were crazy. We went to the Commodore Hotel where the journalists were. During the day, I’d ride around on a moped, and I had my car. The Palestinians of the resistance arranged for us to be able to work and do our job as journalists and witnesses. They knew who was who, and they got us petrol so that we could get around. I went to get gas every day. We changed houses four times during the siege. The Israeli army wanted to assassinate Arafat, and they weren’t handling it with velvet gloves, destroying whole buildings thinking they could get to him. Often there were dozens of dead and wounded but no trace of the PLO leader. One time a building very close to ours was bombed.

Was this a special time for you and your friends?

Well, if you ask those who lived through the siege... They’ll all tell you it was the best time of their lives. As crazy as it may sound, it really was the happiest time of my life, of our lives. Because at that moment, your reasons for living are multiplied by 1000, as you’ve chosen to stay there, you believe you’re defending a cause. Similar to what artists and intellectuals like Capra or Hemingway did during the Spanish War. It was an act of resistance. What right do you have to come and occupy Beirut and Lebanon? That’s the question we were asking the whole world. By being present there, we were bearing witness, and we were with those who were being attacked and bombed. Everything was powerful and intense. It was an exceptional moment, but it was also destructive. Afterwards, you’re no longer afraid of anything. You go so far that you acquire a certain wisdom. And when I’m confronted with a film or a work that evokes war without sincerity, I’m outraged: that’s not the truth. So you blame yourself for being like that. I am authentic! When you’ve gone that far, with such sincerity, you’re in need of urgency in art or journalism.

Then you immortalized the departure of Yasser Arafat and the PLO fighters with The Boat of Exile. They left Beirut and headed for an uncertain place and future.

When I shot these images, I really felt like I was living a historical moment. I didn’t want to leave the city, and I hesitated before getting on the boat. Besides, did those who provided the boat taking Arafat and his troops deliberately choose a boat named “Atlantis”? The name of the boat was the central theme of the filming. And now, this film is part of the history of the Palestinians. I gave them a copy. It’s dedicated to them.

I imagine that many reporters or documentary filmmakers would have liked to have been present on the boat to immortalize that moment, but you were the only filmmaker authorized to do so.

A few months ago, I ran into Elias Sanbar in Beirut – he was signing his Dictionnaire amoureux de la Palestine4 – and we had dinner together with other friends. When I reminded him that I still didn’t know who had given me the permission to get on the boat, he answered: “Oh well... Really, you still don’t know?” (with an air of: “it was Arafat, of course”). My house had burned down at the beginning of the siege, but I hadn’t left the country.

- 1His PhD thesis has been published online: www.111101.net/ Writings/Author/Fawwaz_Traboulsi/. It has been translated into English as A History of Modern Lebanon (Pluto Press, London, 2007). Traboulsi is the author of many political books and essays in Arabic.

- 2Les moi volatils des guerres perdues (1996) and Sous le soleil d’Occident (1998).

- 3The author’s first name, Etel Adnan, is sometimes spelled “Ethel”. Her novel Sitt Marie Rose was published by Editions des Femmes in 1978, and has recently been republished by Editions Tamyras. Adnan is the author of many works (of poetry and prose) in French, English and Arabic.

- 4Published by Editions Plon in 2010.

Originally published as ‘Documenter et conter les tourments du monde’ in a more extended version in La Furia Umana paper#7 (November 2014). A previous version was published on www.criticalsecret.net in 2013.

Image (1): Filming Beirut, My City (1982). Picture by Farida Hamak

Image (2): With combatants of the Polisario Front while filming Sahara Is Not for Sale (1977)