René Vautier: Duties, Rights and Passion of Images

René André Georges Vautier was born on 15 January 1928 in Styvel, a working-class district in Camaret-sur-Mer, a small fishing port at the tip of Finistère, to a laborer, Georges Jean Vautier (born in Cherbourg on 15 February 1900), and a primary schoolteacher, Léonie Marie Perrine Créteaux (born in Morlaix on 27 June 1890). Member of the French Forces of the Interior (Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur), he was decorated with the Croix de Guerre at the age of sixteen thanks to the following service record.

“Enlisted in October 1943, at the age of fifteen, in Quimper’s VENGEANCE intelligence group, where he carried out numerous missions in complete disdain of danger; he remained affiliated to this group until its dissolution, brought about by the German army’s arrest of its chief and a part of its workforce on 22 April. He could escape arrest himself only after stunning the rival soldier with a kick to the groin, following which he had to leave Quimper for some time.

In June and July 1944, he served as an intelligence officer for the Communist Party, French Forces of the Interior of South Finistère. Risking his life and with the help of a colleague, he created a map of the firing angles of German bunkers on the South Finistère coast.

Confined in the city held by Germans during the battle for the liberation of Quimper, he made his way out with a colleague, bringing back two crates of grenades for our troops. Finding the shipment inadequate, he repeated his action, under crossfire from the enemy infantry, and rejoined our ranks with a new load. In the course of his action, he had his clothes penetrated by bullets. After this, despite the prudent advice of his colleagues, he crossed enemy lines, got back to the grenade depot and stocked up. Alone and armed with grenades, he welcomed the first FFI patrol entering Quimper the following morning.

Despite his young age (16 years), he then enlisted in the 6th company of the FFI of South Finistère, and from 11 August to 12 October, he served with honor and loyalty in the battle for the liberation of the Crozon peninsula. During the same period, he rendered great service to Lieutenant Stephan’s counterespionage network.

He was commended at the regiment level and decorated with the Croix de Guerre with a bronze star.

Based on citations from Squad Leaders:

FLOCHLOY, Section Leader, VENGEANCE intelligence.

PHILIPPOT, Major, commandant of the F.F.I of South Finistère.

DANION, Captain, commandant of the 6th Company of the F.F.I of South Finistère.

STEPHAN, Lieutenant, commandant of counterespionage and intelligent service.

For the General, commandant of the XIth Military District:

Corcuff.”1

Coming out of the Second World War, René Vautier decided once and for all to fight not with weapons but with a camera. In 1946, he applied for the IDHEC (Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques) where, in November, he came first in writing and second in the oral exam of the combined Direction and Production department. His batch, the fourth, notably included Claude Sautet, Jean-Jacques Sirkis (future co-director of Tunisian Earth, 1951) and Mustapha El Attar. His friend and future cameraman, the filmmaker Yann Le Masson, would be part of the ninth batch.

In 1947, one of his professors made the following assessment of him at the IDHEC:

“Vautier, René, 19 years.

Particularly brilliant in tests.

Intelligence: best results of his batch.

His sharp-mindedness, ingenuity,

logical and critical intelligence,

make him a subject of particularly gifted intellect.”2

During his studies, René Vautier secretly participated in the making of The Great Miners’ Strike, a collective work signed by Louis Daquin (1948)—a fact left out in the note published in the Annual Report on Former Students of the IDHEC in 1956. On the other hand, it has the following detail:

“Film activities.

Short films:

1949: Assistant-trainee on Medieval Images (Réal. W. Novik)”3

Produced in 1948 by the General Cooperative of the French Cinema (Coopérative Générale du Cinéma Français, created in 1944 at the initiative of the Committee for the Liberation of French Cinema (Comité de libération du cinéma français), the French Communist Party and the General Confederation of Labor (Confédération Générale du Travail, CGT) and co-founded by Louis Daquin, it produced, for instance, The Liberation of Paris (Committee for the Liberation of French Cinema, 1944), The Eye of the Storm (Jean-Paul Le Chanois, 1944), The Sixth of June at Dawn (Jean Grémillon, 1944), or The Battle of the Rails (René Clément, 1945), Medieval Images is a seventeen-minute documentary on everyday life in the Middle Ages as testified by 14th and 15th century miniatures from the collections of the French National Library (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, BNF). Exclusively made of reproductions photographed in extreme closeups, thanks to a camera “entirely transformed” by William Novik,4 “a genius handyman,” the film, shot in Technicolor, received a prize for its color at the Cannes Festival of 1949. The project turned out to be all the more instructive because René reprises the exact principle in Algeria, a Nation (Jean Lodz and René Vautier, 1954), a study of the iconography dedicated to Algeria preserved at the BNF – but from a polemical perspective, since it’s a question of claiming, in the name of the past, independence for this country that’s not a sovereign nation anymore; and then in The Blood of May Sowed the Seeds of November (1982), which extends the collection of images and texts to contemporary artistic practices. One could suppose that, with this initial experience as a trainee on Medieval Images, a sense of the history of images took firm root in the register of fundamental critical resources for René Vautier: images of the past become effective allies here in battles of the present.

In light of this initial experience, one also notices the genetic link between the cinema of French Resistance and internationalist films made in solidarity with national liberation struggles. The metaphor of the African “Oradours” coined by Africa 50 is also rooted in this transitive history.

The biographical note of the IDHEC goes on:

“1950: Scriptwriter, director, cameraman, editor, sound engineer on Africa 50, gold medal at the Warsaw Festival.

1952: Director, cameraman, editor, sound engineer on

- Île de Sein

- Faces of Brittany (in color)

- Bro-Vigoudenn (in color)

- Cain (advertisement in color).

Scriptwriter, director, cameraman, editor, actor, sound engineer on

- Restorers of Cathedrals

- Mountain in the Sea (in color)

- Poitou, Centuries in Images (in color)

- Land Without Water

- Odet, A Breton River

1953: Co-director of Others Are Alone in the World! Or Henri Martin, Sailor from France.

1954: Director on A Man Is Dead, or Brest on Strike.

1955:

- Pedagogical consultant on Open Air (Dir. J. Venard)5

- Technical consultant on Warsaw Celebrates (collective project).

Other film-related activities:

Since 1954: Administrative secretary at the Technicians Union, member of the Union Office.”6

Let us note that most of these short films, if they aren’t lost (A Man Is Dead), are yet to be discovered.

During his studies, René Vautier also secretly participated in the making of The Great Miners’ Strike, a collective work signed by Louis Daquin (1948). In 1950, despite French censors who confiscated a large part of his film reels, he successfully completed Africa 50, the first French anticolonialist film, a masterpiece of political cinema, which brought him thirteen indictments and a prison term of one year. Thereafter, at the cost of physical injuries (he says jokingly that he must be the only director to have a piece of camera in his skull, on account of coming under fire on the Morice line between Algeria and Tunisia), at the cost of numerous battles and some years in prison, René Vautier’s struggle against all forms of political, economic and cultural oppression never ceased. His fight progressed on multiple fronts:

- Against capitalism (passim, and particularly in A Man Is Dead, 1951, Transmission of Worker Experience, 1973, When You Said Valéry, 1975);

- Against colonialism and, more particularly, the Algerian War (Algeria, a Nation, 1954, Algeria Burning, 1958, To Be Twenty in the Aures, Technically So Simple, The Caravel, all three in 1971, as well as recordings of numerous testimonies of torture);

- Against racism in France (The Three Cousins and Gorse, 1970, Immigration: Amiens, 1984, To Live and Work, Together, 1986, French, You Said?, 1987);

- Against apartheid in Africa (The Bell Rang for the Dead, 1970, Frontline, 1976);

- Against nuclear industry and pollution (Black Oil, Red Anger, 1978, Paris for Peace, 1986, Pacific Mission, 1988, Hirochirac, 1995);

- Against the extreme right-wing in France (About the Other Detail, 1984-88).

His fights are often also affirmative:

- Fight in support of women (When Women See Red, co-directed with Soazig Chappedelaine, 1977);

- Fight for Brittany (Alan Stivell and The Fish Commands, 1976, Carte Blanche to Gilles Servat and Carte Blanche to Glenmor, 1977, The Scorpion of Saint-Nazaire, 1980);

- Fight for the rehabilitation of victims of injustice, often forgotten from history (Chateaubriand, Living Memory and Tournevache, 1985, Mys and Thienot, 1990);

- Essays on collective representations and their political stakes (passim, notably in The Blood of May Sowed the Seeds of November, 1982, And the Word Brother and the Word Companion, 1988).

Evidently inseparable (Africa 50 details the connections between capitalism and racism), the fronts are explicitly linked in certain films, such as The Madwoman of Toujane (co-directed with Nicole Le Garrec, 1974), the filmmaker’s favorite work, which welds together Algerian resistance and Breton autonomy in an interrogative and profoundly desperate way.

Simultaneously, René Vautier created logistical initiatives, the necessary means for the production and exhibition of films fighting state-owned and commercial channels. As director of the Algiers Audiovisual Center (Centre Audiovisuel d’Alger) between 1961 and 1965, he trained the first generation of Algerian filmmakers and guided the collective project People on the March, on the war and the first year of independence. In parallel, he created Ciné-Pops, a popular association for “civic culture through film.” In 1972, he founded the Brittany Cinema Production Unit (l’Unité de Production Cinéma Bretagne), whose slogan proclaimed “From colonialism to socialism.” In 1984, he set up “Images without Channels” (Images sans chaînes) to exhibit films censored by French television channels. During the 2000s, he godfathered the Zaléa TV experiment, an attempt to create a free television via terrestrial network. A new generation took inspiration from such examples: in 2006, René’s daughter, Moïra Vautier-Chappedelaine, set up the Mas O Menos association, dedicated to retrieving, restoring and distributing a filmic heritage scattered by historical emergencies; in 2012, the DHR cooperative (Direction Humaine des Ressources, “Human Management of Resources”), co-founded by Vincent Glenn in 2006, distributed the restored version of To Be Twenty in the Aures.

From Resistance to Anticolonialism

In Africa, as early as 1946, a cameraman (anonymous till date) filmed the first rallies of the African Democratic Assembly (Rassemblement Démocratique Africain) in 35mm, in particular the speeches of Félix Houphouët-Boigny and Gabriel d'Arboussier, then parliamentary representatives of the colonies, who sat beside the French Communist Party. Edited together under the title Popular Assemblies in Africa, some of this (soundless) footage served as raw material for René Vautier’s Africa 50.

In 1949, The Battle for Life by Louis Daquin (a communist and a resistance fighter, he worked at the IDHEC where, in 1948, he hired the very young René Vautier to work as a trainee on The Great Miners’ Strike) documented the First International Congress of the Partisans of Peace, organized by the French Communist Party in Paris on 20 April 1949. The film reproduces an excerpt from the anticolonialist speech by Gabriel d’Arboussier, the general secretary of African Democratic Assembly. “In the great battle being waged in the world between forces of good and forces of evil, between forces of peace and forces of war, between forces of freedom and forces of oppression, no one today contests the eminent and painful place of colonized countries and peoples. Nor does anyone today contest the fact that the colonial system is a natural extension of the capitalist system whose expansion resulted in the divvying up of less developed countries among the most economically developed countries. Colonized populations have thus verified the truth of the famous maxim that a people that oppresses another cannot be free. The right of people to self-determination, the respect for their national sovereignty, is a categorical imperative.”7 Reinforcing these words on the reverse shot are views of delegates from Africa and Indochina, images of colonial exploitation in fields and ports. The title Louis Daquin chooses is a quote from Louis Aragon’s closing speech at the Congress, “the battle for peace, that is to say, the battle for life,” repeated by the voiceover at the end of the film. In other words, this phrase sums up the anti-North Atlantic Treaty, anti-NATO, anti-Marshall Plan and pro-Zhdanov communist policy. Shot by a team of young militants, The Battle for Life served as the political platform for anticolonialist films produced by the French Communist Party and its satellites. Africa 50 pays explicit tribute to it: its last words invoke the “neck and neck” race between the people of France and the peoples of Africa to “win the battle for life.”

Africa 50 is the first film credited to René Vautier, twenty-one years of age when he left to shoot in the colonies of French West Africa. Despite the extraordinary and epic character of his act, René Vautier had predecessors at the IDHEC as far as shooting in Africa was concerned. In June 1946, Jacques Dupont, student of Direction and Production (first batch), published a “Manifesto”: in opposition to “super-productions bastardized from literature and theatre,” he called for an independent cinema “in touch with reality” that could help “joyfully give birth to a more human and more just society.”8 Jacques Dupont started work on four films in French Equatorial Africa under the aegis of the Museum of Mankind (Musée de l'Homme) as part of a mission headed by André Leroi-Gourhan and Édouard Trezenem. Two other IDHEC students set off with him: director of photography Edmond Séchan and his assistant Régine Artarit. The musicologist Gilbert Rouget was also part of the expedition, along with a sound engineer, André Didier. Jacques Dupont described the difficulties of his shoot in Congo and, later, Gabon.9 He brought back three short films with him: In the Land of the Pygmies (1946), Pirogues on the Ogooué (1947) and Congolese Dances (1947). In 1950, a second mission took him to Hoggar-Congo-Niger, from which he brought back five films, including The Large Huts (1950). The future director Jean Prat (then a student of the third batch) analyzed Pirogues on the Ogooué in these terms: “For most of the viewers, negroes are black men with large lips and crinkly hair. Pirogues on the Ogooué makes us glimpse the surprising complexity hidden underneath this general term, the hatred between tribes, the temperaments, the chauvinisms, the artistic tastes, the economic relations delineated as areas of influence as rigorous as arrondissements.”10 Such films were at home in the colonial framework put in place by the French government of the time and fed into its ideology, willingly or not. Jacques Dupont later participated in the activities of the Secret Army Organization (Organisation Armée Secrète), notably during the Algiers putsch whose echoes reach the exhausted soldiers of To Be Twenty in the Aures via radio. One could hence presume that, when René Vautier left for Africa himself, it was also against such colonial projects undertaken by his fellow students. This antagonism between student filmmakers persisted across generations since, in 2010, Jacques Dupont’s daughter, Claudine Dupont-Tingaud, elected county councilor of the National Front – imprisoned at the age of 17 for her activism in support of French Algeria, like her father – was the object of a defamation lawsuit initiated by René Vautier and the filmmaker Mehdi Lalloui, whose concern was the writing of history through films.11

While Jacques Dupont’s African films were supported by the Ministry of Overseas France and the Ministry of Air, in the course of his shoot, René Vautier was pursued by administrative and police authorities, and experienced countless extraordinary adventures, which he recounts in detail in Citizen Camera (Caméra citoyenne). He explains his motivation: “I think what sustained me during that time (the living conditions weren’t easy, no money, no medicines—we were becoming real laboratories for colonial diseases, medical cases!) was rage. I’d fought against Nazi occupiers and I saw Frenchmen who were maintaining an ‘order’ in Africa similar to what German officials wanted to impose on us.”12

International political context shaped the film too. In 1947, the “Zhdanov Doctrine” was proclaimed, according to which the Soviet Communist Party must support the struggle of colonized countries in Asia and Africa to counter the “capitalist bloc.” A young French communist organically dedicated to all fights against oppression, exploitation and racism, René Vautier left for French West Africa under the aegis of the League for Education (Ligue de l’Enseignement), whose name appears on the film’s first title card. Founded by Jean Macé in 1866 to defend a popular and secular education, the League was then home to a number of activists in Africa who would go on to become leaders in liberation struggles, to begin with, Ouezzin Coulibaly, in charge of the League in Treichville, which housed René. In October 1946, Coulibaly took part in the founding of the African Democratic Assembly (Rassemblement Démocratique Africain, RDA), a seminal emancipation movement, whose first great protests in Treichville the end of Africa 50 documented. In 1949, while René filmed, the RDA organized its first great political events, which predictably led to even more colonial repression. Among these, in December, were a woman’s march towards the Grand-Bassam prison and a strike of the revenue office violently repressed by the army: “Coming from Bamako towards Abidjan, I and Raymond Vogel followed the trajectory of one of these punitive military columns.”13 The French army committed “massacres in Bouaflé on 21 January (3 dead), in Dimbokro on 30 January (14 dead, 50 wounded), in Séguéla on 2 February (3 dead)”:14 the names listed by the film, “Agboville, Dimbokro, Séguéla, Daloa, Bouaflé, Kétékré,” resonated as so many bloody revelations to the French public opinion. On 26 February 1953, the National Assembly voted in favor of amnesty for colonial crimes committed in Africa and Madagascar, especially in Ivory Coast: “Full amnesty is granted for crimes, infractions and offenses committed in Ivory Coast between 1949 and 1950, during events known as the ‘Ivory Coast incidents.’”15 Dramatically, the list of places affected by the aforementioned “incidents” turns out to be even longer: “Treichville, Bouaflé, Zuénoula, Toumodi, Kouenoufla, Sietinfla, Simfla, Dimbokro, Séguéla, Daloa, Afïery, Agboville, Kétékré-Bonikro, Odienné, Boundiali, Abengourou, Guiglo…”

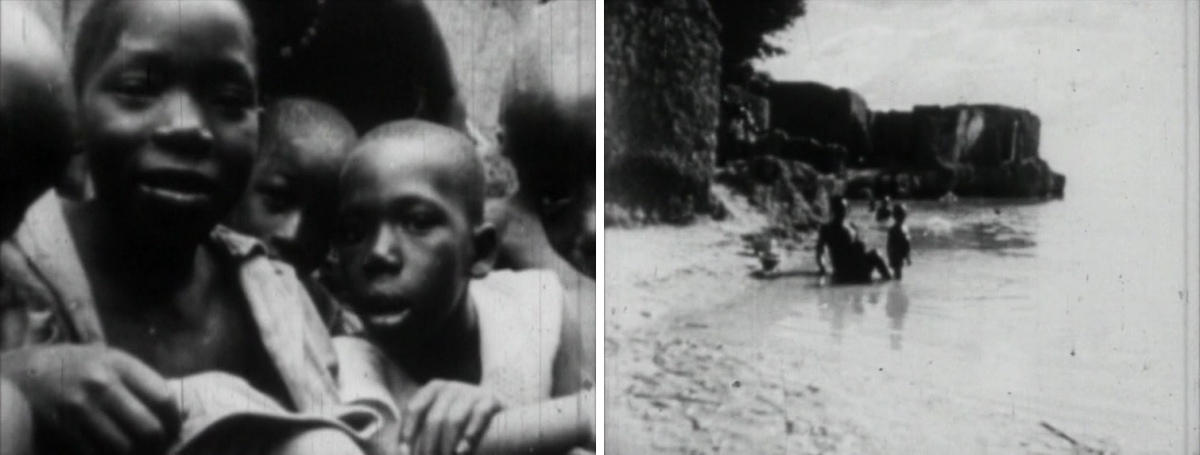

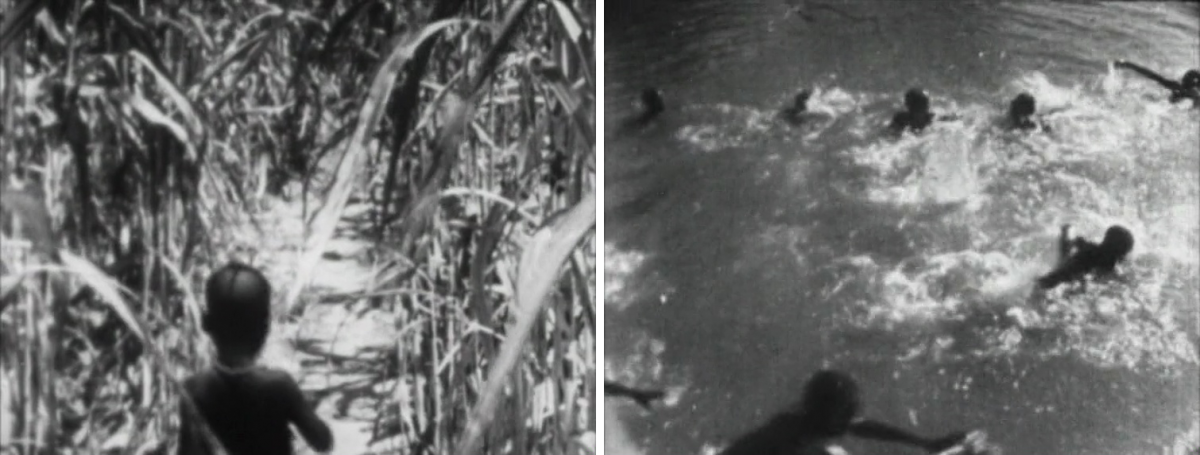

Africa 50 comes across as a singularly well-documented filmic pamphlet: while precise profit numbers of French and western companies are listed on the soundtrack, the imagery picks out traces of colonial abuse—structural ones of organized pillage and factual ones related to military repression. In less than twenty minutes, the film takes us from the Africa of time immemorial (landscapes with plains and rivers, artisanal and agricultural activities, families and games), through a study of the misdeeds of colonialism which took hold from 1830 onward, to end on contemporary emergence of African emancipation movements, which will have their first political success after the middle of the decade, towards 1956. Africa 50 combines various dimensions of visual polemic: it gives information about a situation of economic and political oppression; it deconstructs the ideology of progress and points out its racist presuppositions; it calls for a struggle. And, like how Algeria, a Nation announced an inevitable independence in 1955, the collective surge with which Africa 50 ends, beneath its appearance of optimistic rhetoric, is no less of a date with history of an impeccable precision. Such foresight, which characterizes the entirety of René Vautier’s journey, is based at once on a political analysis, on his experience as a resistance fighter against Nazism and his absolute confidence in the revolutionary power of the people.

As described in Citizen Camera, three-fourths of Africa 50’s reels were confiscated by the French police from the premises of the League of Education in Paris—such that one could always hope to discover the film’s initial rushes in the archives of the Île-de-France prefecture, the Interior Ministry or the Defense Ministry. By swapping full reel cans for empty ones, René Vautier retrieved material that allowed him to edit the twenty minutes that remain today. He wrote and read the film’s text himself and entrusted the music to the group of the Guinean poet, novelist, musician, playwright and activist Keïta Fodéba, a member of the RDA, banned in French West Africa, and who had just created the “Sud Jazz” orchestra in Paris in 1948. It was the first time that an African music served as the score for an entire film. In 1956, having become the director of African Ballets, Keïta Fodéba made a contribution to the First Congress of Black Writers and Artists in which he elucidated the values proper to African avant-garde artists. “Let’s recall that certain ancient civilizations are dead because, having reached their peak, they couldn’t renew themselves upon contact with external cultural currents! The role of African avant-garde artists must involve bringing out characteristic and essential elements of our cultures, while preserving their typical originality during our interactions with the west.”16 A position that, in hindsight, sheds light on the intellectual conditions enabling his participation in René Vautier’s film. Keïta Fodéba met a tragic fate: he was shot by Sékou Touré’s government in 1969.

The dangerous political conditions that René Vautier faced and surmounted at every stage of the making of a film wrested from colonial violence explain the sweeping character of his passionate words, as though, beside virtuoso essay sequences like those about economic vultures or those that describe the exploitation of labor power, the filmmaker didn’t have enough shots to visually document all his statements—in particular, those on the assassination of African militants, such as Mamba Bakayoko, whose name the film saves from oblivion and western coverup. But as René Vautier once elegantly put it: “the scars are part of the film.”17 Back from its war all stitched up, the film contributed in a manner that was pioneering, modest and masterful at once to the wars of liberation in Africa, one of the most glorious pages of the 20th century.

The massacres and struggles in Africa didn’t cease to leave their trace in René Vautier’s films: thus the women’s march toward the Grand Bassam prison on 24th December 1949, to demand the release of their spouses, resonates with the much-less-tragic situation of When Women See Red; thus the lifelong struggle, starting from The Great Miners’ Strike, continuing in A Man Is Dead and ending with Histories of Images, Images of History, to get governmental responsibilities acknowledged and to do justice to the sacrifices of militants, including posthumously. If individual memory feeds on forgetfulness to be able to evolve, the demands of justice in view of collective history, for its part, allows neither negligence nor rest.

In 1955, with the help of prints and historical documents, René Vautier made Algeria, a Nation, a history of colonization and call to independence, from Paris. Then, on Algerian soil, with trainee filmmakers, he secretly made films that constituted some of the most essential documents about the history of the war of liberation: The Nurses of the ALN, The Attack of the Ouenza Mines, The Voice of the People, Algeria Burning (1956-58), which supplied the material for People on the March (1964).

Stylist, Logistician, Essayist

Rich with (and rich only with) his seven decades of fights, and originally inspired by Joris Ivens’ example, René Vautier represents the archetype of the politically engaged filmmaker. His technical and logistical knowhow, his capacity for historical analysis, his intrepid tenacity fostered, on one hand, an extreme aesthetic rigor, capable of expressing his epic grandeur in the immediate present, and on the other, a constant formal inventiveness, thanks to which he surmounted the practical difficulties associated with a cinema of “social intervention.”

For the television program “Short Circuit,” which devoted a reportage to him in 2003, we asked René Vautier to kindly define cinema of social intervention and establish its principles. Upon consideration, he left the following message on the answering machine, read out with a laughter in his voice: “Among the wealthy and the critics who suck up to them, the cinema of social intervention was long considered the bastard child born of the illicit copulation between a camera and an imagemaker procreating against the powers that be.” For the reportage, titled “René Vautier, a hard-fought cinema,” he defined 5 principles:

“5 ground rules for a politically engaged cinema

1. The task of bringing back real images rather than narrating false stories.

2. “One must not let governments write history alone, the people must work at it” (Kateb Yacine).

3. Write history through images. Now.

4. Create a dialogue of images in times of war.

5. Faced with official disinformation, practice and spread counter-information.”18

René Vautier’s choices and gestures imagine, experiment with and establish a revolutionary conception of cinema. In practical terms of production, shooting, conception, editing and distribution, in stylistic terms of the documentary, essay or fiction, every filmic gesture is rethought in the light of collective ideals—including the questions of film history and preservation. René Vautier develops, in fact, a critical conception of what a national or regional film library should be: not a depot of film cans, but “a place in which to remember a non-subjugated cinema and which allows for the preservation of that which was, temporarily, prohibited.”19

Marked by the maiden experience of The Great Miners’ Strike, a collective film from 1948 during the course of which René was arrested by the Republican Security Companies (Compagnies républicaines de sécurité) at the port of Dunkirk, and which was banned and resulted in a decree instituting a non-commercial certificate for every film screening, Vautier’s body of work devoted itself entirely to the concurrent liberation of people and images. His fight against all forms of prohibition and oblivion manifested itself even in his smallest gestures. On 15 October 1953, he responded to the Association of Former Students of the IDHEC under the title “Personal Remarks and Desiderata”:

“Don’t wish to see a reunion of IDHEC students sponsored by the government (directly or through an intermediary).

Think that an Association of Former Students would make sense only if it joined the struggle against censorship and governmental interference in cinema affairs.”20

An essayist, pedagogue and critic, René Vautier explicitly devoted multiple films to ethical and practical problems concerning images, motifs and representations. Remorse, made in 1974 but whose script was written in 1956, constitutes a burlesque and biting satire on the cowardice of French filmmakers cooking up a hundred excuses to not engage with immediate history and abandon their responsibilities, and forms a revealing diptych with Alain Resnais’s episode for Far from Vietnam (1967). To Die for Images traces the journey of Alain Kaminker, a sibling of Simone Signoret’s and a cameraman who died at sea while filming in Île de Sein, and draws out a lesson in humanity that his dramatic story bequeaths us. And the Word Brother and the Word Companion describes the role of poets and their (literary) images during the Second World War, which allows for a response to Hölderlin’s haunting question, “What use of poets in a time of distress?” Destruction of the Archives at Fort du Conquet, shot by Yann Le Masson in 1985, shows René Vautier walking over kilometers of filmic and non-filmic documents chopped up with an ax and covered with oil by an “unidentified” commando: this modest and deeply moving 16mm film constitutes one of the most eloquent emblems of the power of images, which must be vehemently attacked—a modern filmic chapter in the long history of vandalism and desecration. Films in the form of essays on purgative representations (Algeria, a Nation), on self-censorship and images not made (Remorse), on images covered up (critique of disinformation at the periphery of Black Oil, Red Anger, televisual prohibitions in Break the Gag), on inaccessible images (footage confiscated from Pierre Clément by the French army), on his own practice as a political filmmaker (War of Images in Algeria, 1985)… The title card that opens the magnificent demonstration on the subject of colonial representations of Arabian and Algerian peoples in The Blood of May Sowed the Seeds of November summarizes a life’s work: “Images to write History, together.” The work accomplished during sixty-seven years of intense and fraternal activism offers an inexhaustible legacy of reflections and actions on what comprises and what could be a visual document, thought through all its possibilities, from its hard-won material complexity to its status as a political, ethical and artistic framework.

Through the totality of his cinematic remarks, oral or written, René Vautier developed a philosophy of image that is as coherent as it is radical. That it’s always expressed in a clear way makes it no less profound and only reinforces its principal demand: effectiveness.

Author vs Owner

Such a lofty idea of cinema implies a daily battle against the powers that be and their agents, from occupying armies to film journalists, which is the least of things—but also against his own allies looking to instrumentalize him, as is evidenced by a disagreement with his colleague Frantz Fanon. One of the most crucial passages of Citizen Camera (the “Abbane Ramdane” chapter) expounds on the conflict that took place in Tunis when René screened footage from the films that he had made underground to the heads of information of the National Liberation Front (Front de libération nationale), firstly Abbane Ramdane, then Frantz Fanon, present there as the director of the Algerian Resistance magazine. From this, one could understand that, even when committed to a cause with all his heart and soul, René Vautier subordinates his images to nothing or no one, not in a proprietary sense (on the contrary, they are offered to anyone who needs them; we find them in numerous activist films and this sometimes results in the loss of precious copies too, as was the case with Algeria, a Nation), but in the name of an inalienable liberty. Emerging from the conception of cinema developed by René Vautier is the principle of an autonomy of images, whose existence, meaning and freedom, established in their own right, must be protected with the most vigilant intransigence: a symbolic and inalienable territory organized in time, from which history can be established. This autonomy (in the literal sense of a singular law) belongs to no one, not to filmmakers, not to cinema and not even to the people whose oppression and struggles these images document; everyone has the right to enjoy them and none the right to own them. This autonomy is in no way a counter-history, it establishes the possibility of an exact history. Such an autonomization, for example, leads René Vautier, in an incredible gesture, to go on a hunger strike to liberate images made by others (Jacques Panijel’s October in Paris). It also explains René’s constant reflection on the topic of preservation and transmission, with regard to not just concerned institutions but also creative gestures.

An activistic transmission of a historical experience, To Be Twenty in the Aures falls in the lineage opened up ten years before by Guy Chalon and Philippe Durand, as the first French feature film directly tackling the Algerian War on the theatre of operations and from the point of view of the conscripts. The film released on 12th May 1972, ten years and two months after the Évian accords.

The structure of To Be Twenty in the Aures alternates linear narrative and flashback and, to a lesser extent, dramatization and documentary footage. René Vautier reuses shots that he, his Algerian students or Pierre Clément had secretly filmed in 1956-57 and edited for the first time in Algeria Burning, at the peak of the war of liberation.21 It’s perhaps here that the source of the visual energy that permeates To Be Twenty in the Aures lies: like Jean-Luc Godard and his shots of Palestine in Here and Elsewhere (1974) or Peter Whitehead and his shots of the revolts at Columbia in Fire in the Water (1977), René Vautier reinvigorates and deploys filmic material that has become indispensable to collective history. But where Godard and Whitehead, in revisiting their visual archive, give in to a melancholy critical meditation of an essayistic order—very personal, even solipsistic— René Vautier offers his in the guise of stock shots burning with the political and ethical experiments of a new generation. In the Aures, the conscripts were twenty years old; in the film, the stock footage is fifteen years old, and their reactivation through fiction participates in a visual battle against falsification and censorship, which ended only after almost three decades, on 2 June 1999, with the recognition of a state of war in Algeria by the National Assembly.

To Be Twenty in the Aures synthesizes a number of films that René Vautier dedicated to liberation struggles since the end of the forties. On a documentary front: Africa 50 (field survey), Algeria, a Nation (reflection on colonial representation), Algeria Burning (battle monitoring), People on the March (collective essay on the birth of a nation). On a fictional front: The Golden Rings, Three Cousins, Gorse and Caravel, four short fables on colonialism in Tunisia, Algeria and France. Not far from the Documentary Theatre practiced by Peter Weiss, Technically So Simple, a brilliant essay in the form of a visual trap about an ordinary executioner, concretely preludes the making of To Be Twenty in the Aures by testing out the enactment of a testimony, gathered from an installer of anti-personnel mines, by a remarkable actor. Derived from the same audio library (800 hours of recorded interviews with young conscripts), To Be Twenty is also inspired by the true story of Noël Favrelière who, in 1951, refused to become an executioner and, instead of executing him, deserted with his designated victim.

A paean to civil disobedience, the film gleefully disobeys all formal conventions and categorizations: bridging militant activist cinema and experimental cinema of performance (in the tradition made famous by Marc’O, Peter Brook, Peter Watkins, Jean-Michel Barjol…), its filmmaking framework consists of immersing actors in conflict situations true to history and letting them make their own choices. We see here a generation of hardened veterans, accustomed to war, to prison, to censorship and to historical violence in its various forms (René Vautier, Pierre Clément, Antoine Bonfanti), lovingly and playfully transmitting something of its experience and its questions to the next generation (Philippe Léotard, Jean-Michel Ribes, Alain et Pierre Vautier, Nedjma Scialom…) through action, in a practical and resolutely non-authoritarian way. To Be Twenty in the Aures transforms twenty years of anticolonial struggle into an anarchist experimental framework.

One must point out that an autonomy of images has nothing to do with the fetishization of a shot, a motif or a medium (film, video, digital), so common among filmmakers. Rather, it has to do first and foremost with a symbolic operation, the responsibility of images in face of history, which subordinates and reconfigures other authorities: participants, author, signatories, context, intertext. René Vautier’s work deploys a precise and broad conception of the functions and uses of images: to document, to tell the truth, to do justice, to testify, to offer proof at a trial, to converse with other images, pieces of information, instructions and signals, to contradict, to counterattack, to convince… René Vautier explicitly invested images with all these duties: but in order for them to accomplish these, he had to also implicitly conceive of a right of images, which makes them irreducible to the host of uses and instrumentalizations they can be subjected to.

Ingenium and Passion

Every film by René Vautier constitutes a pamphlet, a shield for the oppressed and the victims of history, a little war machine for justice. And like weapons in an underground cell, these films serve, are donated, exchanged, lent, thrown away, destroyed, lost, or hidden and sometimes forgotten in their hideout for a long time. In this regard, every work by René Vautier constitutes a special case, an episode in probably the most novelistic story in the history of cinema. Full of scars though they might be, these films are of a real beauty, not only in the aesthetic and stylistic sense, but in the sense of a cinema elevated to the plenitude of its necessity and its powers.

The practical foundation of René Vautier’s filmic gesture is ingenuity, Ingenium, a notion developed by a baroque Spanish Jesuit from the 16th century but which harks back to Greek Cynics, Diogenes, Antisthenes, to the tradition of thinkers and artists who always find the most elegant way to challenge power—a power that we remember only because it was challenged by brilliant thinkers. As one reads in Citizen Camera or in a number of written or audiovisual interviews, turning into a corpse, breaking out of prison and returning to it voluntarily, finding a helicopter within a day to film a forbidden shot, the exploits of René Vautier, a mischievous and tireless being, are countless and could fill several other lives. In her fictionalized memoirs The White and the Red, the journalist Ania Francos traces, through their meetings and reunions, the journey and the motivations of René, whom she portrays as the Jean Le Masson character, a doctor who leaves for Algeria to start a revolution. “He always knew that one doesn’t wage the revolution of others, that one can only die for it. Journalists often asked him why he fought alongside Algerians and why, especially after Den-Den, he continued to fight alongside them. ‘What do you expect from it?’, they asked. He expected nothing. From the beginning, he knew that it was a one-sided love affair and that he had to fight in order for them to accept this gift.”22 Observing René’s constantly sacrificial behavior for the cause of images, including lost images like the ones in A Man Is Dead, it’s hard not to think of a passion. One suffers torture, prison, hunger for the sake of images; for the sake of images, one gets into a fight, constantly flirts with death, witnesses the death of others. There’s an astounding faith at work here, proper to a 20th century man, a secular, revolutionary and collectivist passion, which offers us an idea of what words could have meant for Denis Diderot. For René Vautier, images support a critical truth in an endless visual debate, whose horizon is a more equitable state of the world.

Exemplariness and Complexity

Like that of the Polish resistance fighter and filmmaker Edouard de Laurot, another protagonist of political cinema long neglected by historians, René Vautier’s journey has been the object of novelistic transpositions. But a more complex case presents us with the fascinating enigma of militant exemplariness. In The Deserter (Éditions de Minuit, 1960), an anti-imperialist and anticolonialist novel published by Jean-Louis Hurst under the pseudonym Maurienne – chosen by Jérôme Lindon in response to that of Vercors – the Bernard character, who speaks in favor of the act of desertion to his countrymen called up to Algeria, discovers a poem in a clandestine publication, which he attributes to an “Algerian Maquisard.”23 Produced in its entirety in the novel, this call to solidarity of French conscripts with the Algerian people in struggle shows several signs of affiliation to René Vautier’s work; to begin with, the signatory’s name, “Ferid.”

“Comrades,

The meshes of the night are woven with soldiers,

And these soldiers have the voice of France…

And even so,

The words I have in me,

The words that come from me,

Come also from France,

Just now,

Eleven mines on the bridge

Toppled the heavy wagons

Carrying ore from Ouenza…

And Robert Desnos, French poet, told me

While the smoke scaled the skies

While wavering wagons chose a ballast to rest on

‘I salute you, ousters of railroads, incendiaries,

I salute you after your hard, clandestine work.’24

And then came the planes

Pinning us

Flat under the green trees…

The other side of leaves have a more tender green

That smiles better upon the blue of the sky…

And the buzzing and spitting planes made cries of France

A voice told me, while next to me

lay huddling the child Slimane and the old Rabah,

A voice told me softly,

A voice of France:

‘I salute you, fighters,

Children of the purest smile,

Old men more time-worn than rings,

Images of seasons…’

Nightfall has woven its nets with soldiers

And the words they exchange have an accent of France.

But… Wogs, Ragheads, are these words of France?

Clapping 105s,25 barking tanks

Whistling bullets and yapping grenades…

Are these words of France?

Fighting to escape the ambush

To be only ears

To be only legs

To be only a finger twitching over the trigger…

Freedom is a song of France

That gives rhythm to the weary breath:

‘For I was born to know you

To name you: FREEDOM.’26

As the day breaks over the ruins,

Ali dead, his head cracked open…

‘A man is dead who had no other defense

Than his hands open to life…’27

Ali is dead as the night falls

You salute him, Paul Éluard.

‘A man is dead who had no other way out

Than the one dotted with guns,

A man is dead who continues to fight

Against death, against oblivion…’

These words salute you, Ali,

And these are the words of France…

Comrades, comrades, say it,

The voices that were of France

The freest voices, the strongest

The voices that are still of France

Are they dead?...

Comrades, cry out No!

Comrades, comrades, say it,

Say it out loud!

Say it out quick!”28

The poem is repeated at the end of the novel, reintroduced thus by the narrator: “I remembered the call of my unknown Algerian brother.”29 Could Jean-Louis Hurst, the son of a resistance fighter, an anticolonial activist, a member of the French Communist Party, a deserting officer in Algeria in the manner of Noël Favrelière, be unaware of the real identity of this “Algerian brother”? Did he really find this poem in a clandestine magazine? Conversely, it’s hard to imagine that René Vautier might have written such a call to solidarity expressly for Hurst’s novel, to the extent that Citizen Camera, a recension of cases of literary and filmic censorship, doesn’t mention The Deserter. From this tapestry of political experiences, against the Nazis in France, against torture and war in Algeria, between two generations, between three populations, between documentary and fiction, between anonymity and pseudonyms, between writing and film, between the illegal present and future justice, between call to action and historical reflection, between doubt and action, surfaces the symbiotic and subtle energy so well alluded to by Philippe Grandrieux: “From one man to another, life, infinitely transmitted…”30

At a time when contemporary Europe sinks into full political regression, when the daughter of a lifelong enemy, born the same year and in the same land of Brittany, Jean-Marie Le Pen, makes it to the second round of the presidential elections in 2017 without surprising or outraging anyone, one can only dream of a world where, in secular and republican schools, something is taught about René Vautier’s heroic, romantic and joyous life, where Africa 50 and French, You Said?, which puts the historical strata of national racism into perspective, are screened. A world which, far from fetishes, idols and commercial figurines, would take the incredible courage, historical intelligence and the limitless generosity of, for example, Saul Landau, Haskell Wexler, René Vautier, René Viénet, Jocelyne Saab, Jacques Kebadian, Carole Roussopoulos as benchmarks, a world of uprightness, a world standing upright. In the meantime, let’s apply to René the epigraph by Gaston Bachelard that he placed at the opening of his last film, Histories of Images, Images of History: “The past leaves a trace in the material, it produces a reflection in the present, it’s thus always materially alive.”31

- 1This document appears in René Vautier’s student file preserved at the IDHEC.

- 2ibid.

- 3Annual Report on Former Students of the IDHEC. 1944-1956, Paris, Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques, 1956, 2nd edition, p. 202. Once a film critic, William Novik, a director, cinematographer and CGT activist, was a cameraman, along with André Dumaître, on Alain Resnais’ and Robert Hessens’ Guernica (1949). From 1945 to 1953, at the request of his friend Henri Langlois, he built and managed the collection of books and non-filmic documents at the Cinémathèque française. Among his other short films as director: The Age of Machines (1951), On the Quest for Gold (1951), U. 235 (1954, 19 minutes), which focused on the different uses of Uranium, particularly in the nuclear industry – another subject handled later by René Vautier – River of Time (1958), on Iraq, Four Families (1960).

- 4René Vautier, Citizen Camera, op. cit., p. 80.

- 5René Vautier was also involved in the making of Days of Spring 1948, Jean Venard (1948, 23 minutes), a film about youth festivals organized by the CGT.

- 6Annual Report on Former Students of the IDHEC. 1944-1956, ibid.

- 7Transcribed by the Ciné-Archives site.

- 8Jacques Dupont, “Manifesto,” Bulletin of the IDHEC, issue 2, June 1946, p. 16.

- 9Column “What They’re Writing Us,” Bulletin of the IDHEC, issue 7, January-February 1947, p. 20.

- 10Jean Prat, “Pirogues on the Ogooué,” Bulletin of the IDHEC, issue 10, January 1948, p. 10.

- 11Quimper Court, April-June 2009. Claudine Dupont-Tingaud was found guilty and fined.

- 12René Vautier, Citizen Camera, op. cit., p. 35.

- 13René Vautier, Citizen Camera, op. cit., p. 36.

- 14Yves Benot, Colonial Massacres. 1944-1950: The Fourth Republic and the Reining in of the French Colonies (La Découverte: Paris, 1993), pp. 148-149. The 6th chapter, “Massacres and inquiries in Ivory Coast—Ivory Coast, 1949-1950,” allows us to retrace the repressive environment in which René Vautier shot Africa 50.

- 15Official Journal of the French Republic. Parliamentary Debates of the Fourth Republic and its Constituents, 1st Session of 26th February 1953, p. 1368. Accessible online.

- 16Keïta Fodéba, “African Dance and Stage,” “Contributions to the First Congress of Black Writers and Artists,” special issue of Présence Africaine, no. XIV-XV, June-September 1957, p. 205.

- 17René Vautier, conference at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Centre Michelet, seminar “The history of avant-garde cinema told by its protagonists, even,” 19 February 2002.

- 18Nicole Brenez and Khalid Mamoun, “René Vautier, a hard-fought cinema,” 2003, 10 minutes, Court-Circuit, the Magazine, produced by Arte.

- 19Conversation from 18 August 2009.

- 20René Vautier’s student file preserved at the IDHEC.

- 21Pierre Clément went to Tunisia in 1957. He shot a lot of footage, notably a film denouncing the Sakiet Sidi Youssef massacres of February 1958. In October of the same year, he was taken prisoner by the French Army while he was shooting on Algerian territory. Sentenced to ten years in prison for breach of external security of the State, he was given amnesty in October 1962. In December 1996, René Vautier filmed an interview with Pierre Clément at the Arab World Institute, which we transcribed and partially published in Cahiers du Cinéma issue no. 561, October 2001.

- 22Ania Francos, The White and the Red (Julliard: Paris, 1964), p. 133. Den-Den is the name of the prison where the Provisional Government of the Algerian Revolution (Gouvernement Provisoire de la Révolution Algérienne) had René Vautier and other members of the National Liberation Army (Armée de libération nationale) imprisoned by the Tunisian National Guard. Ania Francos relates this episode in page 99. In 1970, René Vautier used the pseudonym “Férid Dendeni,” “the man from Denden,” in the credits of The Bell Rang for the Dead. René quotes several other passages from The White and the Red in the “Myth and Reality” chapter of Citizen Camera.

- 23Maurienne, The Deserter, Éditions de Minuit: Paris, 1960), p. 87.

- 24Robert Desnos, “The watchman of the Pont-au-change,” 1944. The original text of this paean to sabotage and to internationalism during the Second World War reads:

“I salute you, you who sleep

After your hard, clandestine work,

Printers, bomb carriers, ousters of railroads, incendiaries,

Distributors of tracts, smugglers, message carriers,

I salute you all, you who resist, children of twenty years of the purest smile

Old men more time-worn than bridges, robust men, images of seasons,

I salute you from the dawn of the new day.” [Author’s Note] - 25An artillery unit, the 105 cannons were used by the French army in Indochina and then in Algeria. [Author’s Note]

- 26Verses excerpted from Paul Éluard, “Freedom,” Poetry and Truth, 1942. [Author’s Note]

- 27Verses excerpted from Paul Éluard, “Gabriel Péri,” A German Rendezvous, 1944. [Author’s Note]

- 28Maurienne, The Deserter, op. cit., p. 87-88. We have reproduced the spelling and the layout of the poem as it is.

- 29Maurienne, The Deserter, op. cit., p. 125.

- 30Philippe Grandrieux, It May Be That Beauty Has Strengthened Our Resolve. Masao Adachi, 2012.

- 31Gaston Bachelard, Intuition of the Instant (Paris: Éditions Gonthier, 1932).

Translator’s notes

1. For the sake of reading ease, I’ve chosen to translate the names of all films, books, poems, publications, organizations and designations in English even when no known translations exist. For instance, René Vautier’s book Camera citoyenne is translated as Citizen Camera even though no English translation of the book is available. For organizations, I have provided the original names in parenthesis. For military designations of the French army, I’ve tried to use international equivalents, but where a direct equivalent is unavailable, I’ve translated the designation as it is.

2. As is customary with translations from the French, I’ve changed the present tense of the text (“During his studies, René Vautier participates in…”) to the past, except when describing the content of films (“The film reproduces an excerpt from the anticolonialist speech…”).

3. There are a handful of references to “peuples” in the original text, referring to the various populations of Africa involved in freedom struggles. I have retained the plural only in places where it doesn’t hinder comprehension.

4. On the advice of the author, I have rendered the expression “cinéma d’intervention sociale” literally as “cinema of social intervention” in order to emphasize the activist dimension of Vautier’s practice, as opposed to the more common Anglophone term “socially conscious film” to refer to issue-based cinema.

5. The poem excerpted here from Le Déserteur is free verse without a rhyming scheme and with very little wordplay. While a literary translator could no doubt do better justice to the poem, especially within the original context of the novel it appears in, I believe that my translation, quite literal, serves its purpose in this text, which is to describe the poem’s affinities to Vautier’s work as described throughout the essay.

6. I’m immensely grateful to Ms. Brenez for her generous clarifications to the questions I had on some passages of this essay. I’d like to also thank my friend Ruma for her comments on certain tricky turns of phrase.

Originally published as ‘René Vautier: droits, devoirs et passion des images' in Olivier Azam (ed.), Afrique 50 de René Vautier, coll. Mémoire populaire (Les mutins de Pangée: Paris, 2013) and republished in Nicole Brenez, Manifestations. Écrits politiques sur le cinéma et autres arts filmiques (de l’incidence éditeur: Réville, 2019).