François Weyergans (1941-2019)

On May 27, the Belgian-French writer and director François Weyergans passed away on the age of 77. Naturally, the obituaries – brief as they are in the Dutch-speaking part of his native country – focus on his literary career. Weyergans won the Prix Goncourt in 2005 for his novel Trois jours chez ma mère and he had a seat in the Académie française that he took over from Alain Robbe-Grillet after the latter passed away in 2008. His first novel, Salomé, written at the age of 27 but unpublished until 2005, revolves around the journeys of a young filmmaker. Thematically or structurally, his literary work often evokes his earliest devotion: cinema.

Born in Etterbeek, Weyergans aborted his studies in Roman philology and left for Paris to study film at the prestigious Institut des Hautes Etudes Cinématographique (IDHEC). There he showed his strong affection for the work of Robert Bresson and Jean-Luc Godard. At the same time, hardly 19 years old, he started writing for Cahiers du Cinéma in the December issue of 1960 and continued for seven years (until the February issue of 1967) – experiencing the last years of Éric Rohmer as editor-in-chief and the first years of Jacques Rivette’s takeover. “D’ailleurs, cela ne plaisait pas du tout au prof d’avoir un type qui écrivait dans les Cahiers,” Weyergans remembered in a masterclass he gave at the film festival Premiers Plans in Angers in 2006. He followed in the footsteps of his father, the writer Franz Weyergans, who had also been a film critic for La Revue Nouvelle (under the pen name of Jacques Legay).

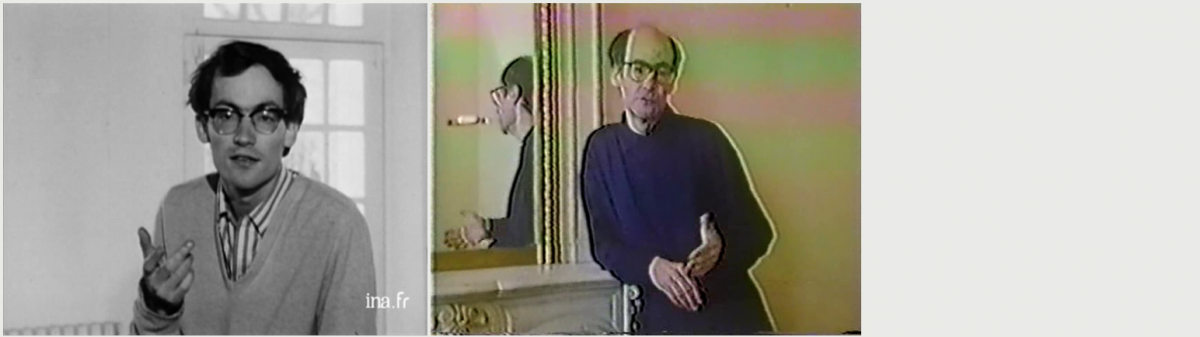

Weyergans started out as an apprentice for Robert Bresson. In 1965, still only 23 years old, he directed Robert Bresson: Ni vu, ni connu for Janine Bazin et André S. Labarthe’s illustrious series ‘Cinéastes de notre temps’. Having never before granted an interview on camera, Bresson received the young Weyergans in his country house. It remains one of the only long filmed conversations with Bresson. In 1994, Weyergans re-edited the film for a broadcast on Arte and agreed to revisit it: “Je ferai une sorte de postface, qui ne posteffacera pas l’émission elle-même... Et aussi une préface de deux minutes, un plan fixe cadré et éclairé par l’ami Raymond (Depardon). En guise de postface on n’allait pas montrer un vidéoclip d’extraits de films tournés entre-temps par Bresson. Je montre une photo, deux affiches – comme dit Bresson: ‘Il faut montrer les choses sans les montrer’.” Almost 30 years later, in the new introduction, he confesses “that Bresson had directed [him] for the questions. These are questions that he had more or less rewritten himself. We made up all the questions after the answers [...] because he likes answering questions he asks himself.” In his epilogue, Weyergans beautifully includes his daughter, writer and actress Métilde Weyergans, who is, in medium close-up, reading fragments of Georges Bernanos’ Mouchette (1937) and Dostoyevsky’s A Gentle Creature (1876) and White Nights (1848). Eventually, Weyergans and Bresson ended up sharing more than expected. Weyergans’ wife, the Belgian Mylène van der Mersch, would later marry Bresson. Possibly, they met during the shooting of the film for ‘Cinéastes de notre temps’ in March. In Au hasard Balthazar, filmed in the summer of that same year, she still appears on the credits as Mylène Weyergans for her role as the nurse of the sick child, but from Mouchette (1967) onwards, she’s credited as his assistent director with her maiden name and became the most important collaborator for Bresson who himself was largely invisible on his sets. Robert Bresson: Ni vu, ni connu (1965/1994)

Robert Bresson: Ni vu, ni connu (1965/1994)

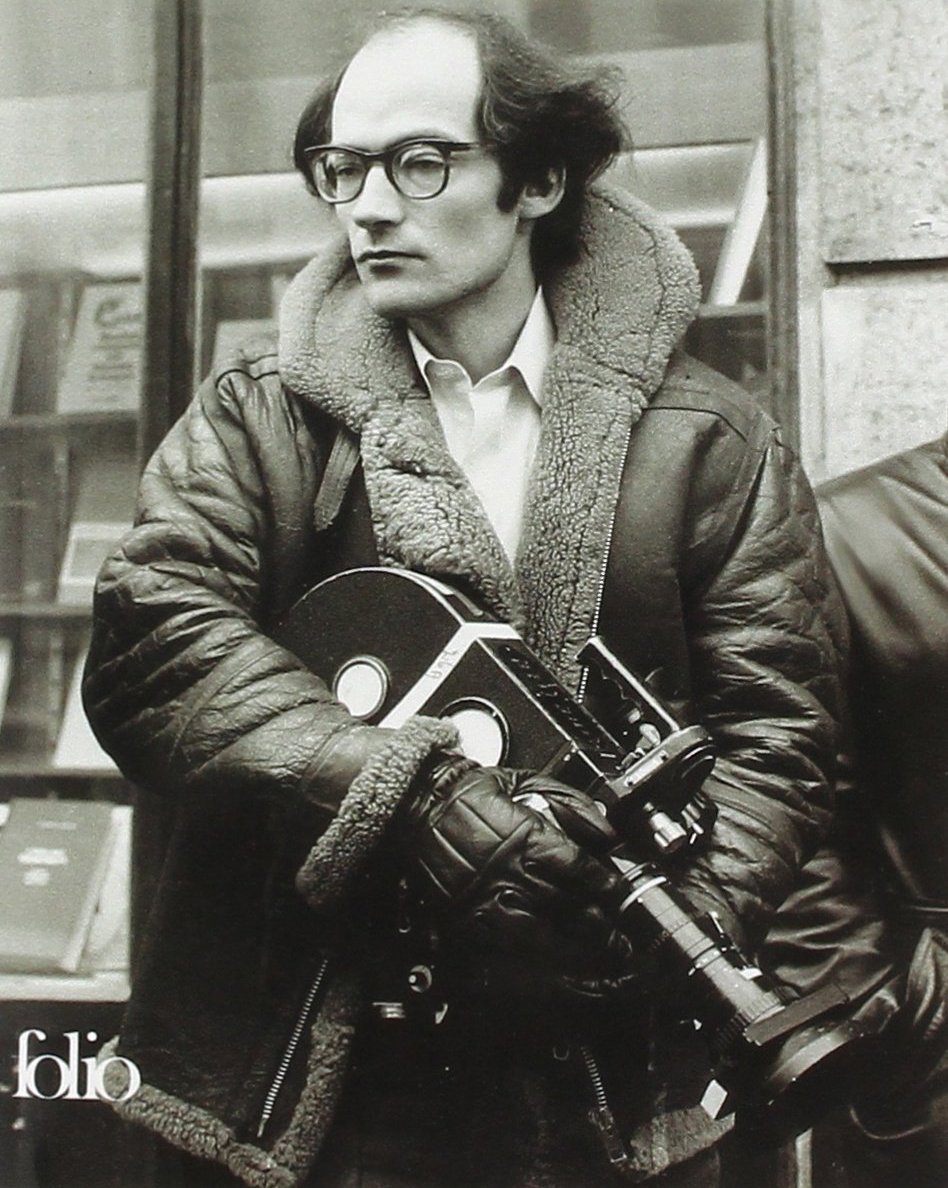

In his early short documentaries, Weyergans explored the fields of dance, painting, architecture, literature and music. His debut, Béjart (1961, 18’), made at the age of 20, “follows the birth of gestures and attitudes, the genesis of a solo and a pas de deux in the bare setting of a dance studio, deploying very long shots of a highly effective severity”1 . François Truffaut responded: “Pendant 18 minutes, j’ai compris la danse!”2 . When the film was refused for the short film festival in Tours, Jean-Luc Godard (who later did one of the voice-overs for Weyergans’ Statues) wrote a telegram: “Comme d’habitude, les films intelligents et audacieux, par example Béjart de François Weyergans, sont et seront toujours refusés au festival de Tours”3 . None other than Max Ernst, Jacques Demy and Roberto Rossellini joined in to support Weyergans. A dozen years later, a sort of follow-up film, Je t’aime, tu danses (1973), was shot over eight days in a rehearsal studio with his friend Maurice Béjart and the young Antwerp ballerina Rita Poelvoorde. Delphine Seyrig, who already lend her voice to the last line (from a poem by René Char) of Béjart, again supplies this film, neither a documentary nor fiction, with a voice-dance counterpoint based on one of Hans Christian Andersen’s tales.4

Béjart was followed by Hieronymus Bosch (1963), Statues (1964) on Gothic sculpture, the tv film Baudelaire est mort en été (1967) and a feature-length documentary that acts as a fiction film, Un film sur quelqu’un (1972), on the pioneer of musique concrète, Pierre Henry. He showed his first short films to Jacques Ledoux, the director of the Royal Belgian Film Archive, and he supported him. His feature debut, Aline (1967), “is a film clearly inspired by Dreyer and above all by Bresson, with short, allusive sequences, the unvarying tone of non-professional actors, a deliberate opaque symbolism, the obsessive presence of objects and recurring close-ups of faces”5 . At the time, Jean-Luc Godard, again, defended Aline fervently. In the two features Weyergans made in the 1970s, he twice worked with Laurent Terzieff, who acted for Rossellini, Pasolini, Carné, Clouzot, Buñuel, Garrel, Godard, Pollet, Kramer and others. After Maladie mortelle (1975), Terzieff was part of the impressive cast that Weyergans managed to get together for Couleur Chair (1978): Anne Wiazemsky, Dennis Hopper, Lou Castel, the model Veruschka, Rolling Stones’ muze Bianca Jagger and Béjart’s star Jorge Donn. Weyergans let them improvise the film from a basic sketch, allowing his actors complete freedom to construct their roles during the course of shooting. It was Weyergans’ last film. None of his work is available on dvd.

- 1René Michelems, “Je t’aime, tu danses,” Belgian Cinema/Le Cinéma Belge/De Belgische Film (Brussel: Koninklijk Belgische Filmarchief, 1999), 518.

- 2“Figures Libres/Freestyle: François Weyergans,” Catalogue Premiers Plans Festival d'Angers 2006, 71.

- 3“Figures Libres/Freestyle: François Weyergans,” Catalogue Premiers Plans Festival d’Angers 2006, 71.

- 4René Michelems, “Je t’aime, tu danses,” Belgian Cinema/Le Cinéma Belge/De Belgische Film (Brussel: Koninklijk Belgische Filmarchief, 1999), 518.

- 5René Michelems, “Aline,” Belgian Cinema/Le Cinéma Belge/De Belgische Film (Brussel: Koninklijk Belgische Filmarchief, 1999), 432.