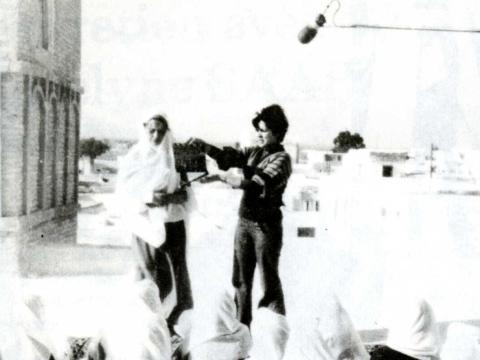

Selma Baccar

Out of the Shadows

I consider what I do as, primarily, bearing witness to my society by way of cinema, with everything that it comprises regarding the contradictions between man and woman, law and practice... I don’t isolate the problem of women from the whole of the society.

Selma Baccar was born in Tunis in 1945. After college, she studied psychology from 1966 to 1968 in Lausanne, Switzerland. At the age of 21, Baccar began to create films with other women at the Hammam-Lif amateur film club. Her first short film, made in 1966, was a black-and-white film called The Awakening that tackled women’s emancipation in Tunisia. She moved to Paris to study film at the Institut de Formation Cinématographique (IFC), after which she worked as assistant director for Tunisian television. In 1975, the same year as the UN’s International Women’s Year, Baccar directed her first feature film titled Fatma 75, which is considered to be the first feature film directed by a woman in Tunisia. In this “analytical film”, as Baccar has defined it, three generations of women and three forms of awareness are related — the period between 1930 and 1938 and the creation of the Union of Tunisian Women; the period between 1939 and 1952, which marks the relationship between the national struggle for independence and the women’s struggle; and finally, the period after 1956 to the present, concerning the achievements of Tunisian women with regards to the Code of Personal Status. “I conducted a series of historical researches, in particular on the participation of women in the struggle for independence and its achievements. I then measured the gap between the Code of Personal Status and its application in practice. Through this film, I wanted to demystify what is called “the miracle of the emancipation of Tunisian women”. Despite being funded by the Tunisian government, Fatma 75 was censored and subsequently banned from screenings in the country for thirty years. In 1990, she became the first woman producer in Tunisia with her production company Inter Médias Production. Selma Baccar’s activism for Tunisian women’s rights led her to an active political career. She also sat on the Assemblée Constituante that rewrote the Tunisian constitution in 2011 to include changes that were heralded by the UN as “a breakthrough for women’s rights”.