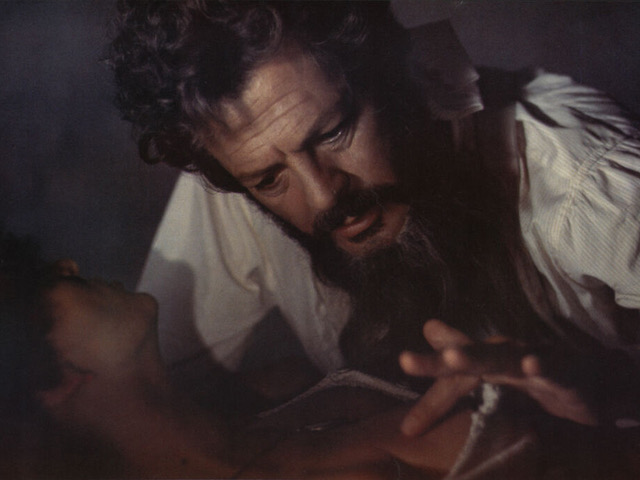

Sicily, 1922, just as the fascists come to power, Angelo Paternò was murdered by Vito Acicatena and everyone in the village knows it: however, no one has the courage to testify at the trial. Months later, a socialist lawyer, wants to convince the widow Titina to ask for the trial to be reopened. Two men fall in love with the widow. The changes in their country's politics ultimately take all three on a journey across the ocean to New York City.

EN

“My greatest desire is to make popular cinema. I continue to do all that I can to avoid addressing an elite, intellectual or otherwise. For example, my first film won fourteen international awards, but it followed the conventional road of the cinema today; it was for the intellectuals. Considering the problem, I changed my politics; I changed my approach, searching for a popular cinema while trying not to reject anything which might enable me to communicate with people. I proceeded with a great faith in the power of laughter and tears, without fearing to be too obvious or to appear banal, always trying to communicate and entertain and hoping, in the end, that people would leave my films with problems to think over and analyze.”

Lina Wertmüller1

Gideon Bachmann: Why did you say you wouldn’t want to be successful because of being a woman?

Lina Wertmüller: I have a reserved relationship to feminism. There are many things they say that I don’t agree with. I understand the need for a breakaway, and in our society, patriarchal for so many millennia, the breakaway must be polemic and aggressive. The need for scandal can lead to all those aberrations. But I simply do not believe that the problem of women is the clitoris instead of the other thing. The problem is on another level. The human being is a human being, and I couldn't care less for the sex they happen to be. The humanity is the only sure thing. There are so many social needs that must precede the sexual ones. What does count is that there is a form of social organization that precludes equality between men and women. This problem center is the family. As long as we continue being organized in family units there is always one – the woman – who pays the double price. This whole business of love and sons, the obligations, and feelings that these provoke, are blackmail weapons. All this is so firmly rooted in us, that it will not be an easy battle to eradicate any part of it. I firmly believe that the family must go.

Lina Wertmüller in conversation with Gideon Bachmann2

“Wertmuller’s powerful 1970s films combined the intense energy and physicality of the commedia dell'arte tradition with the high emotionalism of her theatrical training, and applied them to the post-1968 political consciousness. Her achievement was not met without controversy, however – critical discomfort ran high, especially in feminist circles. Wertmuller’s resolve to communicate her political messages to mass audiences through hyperbolic and grotesque comic techniques raised serious questions about whether or not the regional, gender and class stereotypes which sustain her cinema do not reinforce the public’s most regressive prejudices. If such polemics are an index of success, then Wertmuller’s 1970s production fully achieved its goals.”

Ginette Vincendeau3

“Dealing with Hollywood studios is like being courted by a great prince. At first they’re lovely, murmuring ‘Oh, my sweet girl, how I adore you and want you’ … But you can see in the brightness of their eyes that they know they are the great prince and in the end they are going to break your ass.”

Lina Wertmüller4

- 1Quoted in Dan Georgakas & Lenny Rubenstein, The Cineaste Interviews. On the Art and Politics of the Cinema (Chicago: Lake View Press, 1983), 131.

- 2Gideon Bachmann & Lina Wertmuller, “‘Look, Gideon—': Gideon Bachmann Talks with Lina Wertmuller”, Film Quarterly 30, no. 3 (Spring, 1977): 2-11.

- 3Ginette Vincendeau, Encyclopedia of European Cinema (Los Angeles: Cassell, 1995), 452.

- 4Quoted in Rebecca J. Sheehan, “One woman’s failure affects every woman’s chances: stereotyping impossible women directors in 1970s Hollywood”, Women’s History Review 30, no. 3, 483-505.