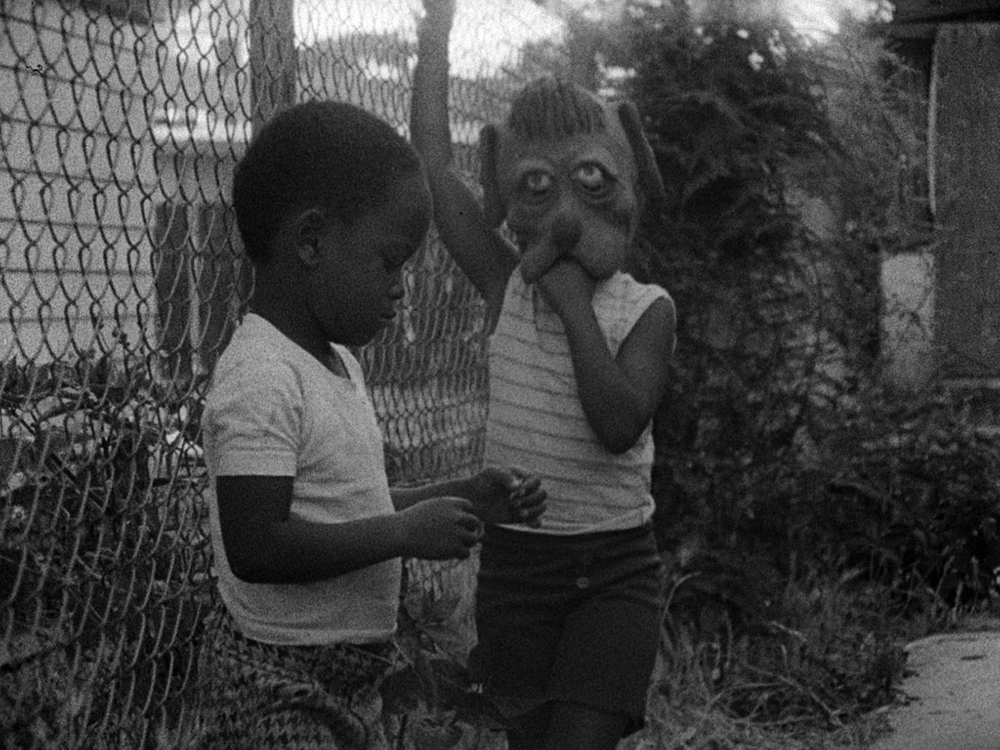

Set in the Watts area of Los Angeles, a slaughterhouse worker must suspend his emotions to continue working at a job he finds repugnant, and then he finds he has little sensitivity for the family he works so hard to support.

“I think that, as I was growing up, disillusionment was inevitable. Growing up was nothing but battling dreams, hopes, expectations of what life would be. Responsibilities, also, had a lot to do with it, and the time allotted to us to do things played a part in it. I do not think that disillusionment is a bad thing. I think that you have to be able to get on your feet and make a choice – either you agree with the current trend or you don’t. You see, illusions are one thing and convictions are something else. Sometimes convictions and illusions get confused, sometimes they inform each other. Illusions and dreams may be lost, but convictions remain. I think that my convictions have been intact.”

Charles Burnett

“At the University of California in the late sixties and early seventies, at a time when the Black Muslims and Black Panthers were making their presence known on and around campus, a small group of filmmakers decided to make visible what had previously remained unseen in cinema: the experience of growing up black in America. They made films that followed neither the blaxploitation strain, with its pimps in platform shoes defying the white establishment, nor the sterile educational strands aimed at providing sociological explanations of inequality and difference. What emerged instead were cinematic portraits of everyday hardship and resistance, showing slices of life in the throes of precarity and discrimination. Of all the remarkable films that were made by this group, which was later designated as the ‘L.A. Rebellion’ movement, one film stands apart for its captivating, timeless vision of a community finding ways to get by and live life in the dusty lots, cramped houses and concrete jungles of South Los Angeles. This film, which was made by Charles Burnett as his master’s thesis at the UCLA film school, is titled Killer of Sheep. It takes us down the corridors of everyday lives in the black ghetto of Watts, where past and future memories of riots are festering, where the brightest light seems to be coming from the shimmers of the ‘no way out’ signs. But rather than setting out to uncover a socio-political reality that lies beyond the surface of what is present, it makes sensible what is too close up to see: the internal ghetto of emotional devastation, suffocation, exhaustion, disorientation. Desperation is always round the corner, but its looming threat is met with resilience, indicative of a capacity to escape from the slipstream of imposed realities and identities. Just like the blues lullabies that drift in and out of the frame, the film draws its strength from its oscillation between disillusionment and promise, between vulnerability and waywardness. Drawing inspiration from Jean Renoir’s The Southerner (1945) and James Agee’s Let us now Praise Famous Men (1941), Killer of Sheep manages to convey a heartfelt sense of dignity and possibility by the agency of nonprofessional actors and location shooting. Although the film was finished in 1977, it took thirty years before the music rights were cleared for commercial distribution. Since then, this tender humanist ode to urban existence is shining more brightly, and perhaps more urgently, than ever before.”

Courtisane

“Killer of Sheep, however, was mostly a reaction to the kind of films I was mentioning earlier: films about the working class made by well-to-do kids, often showing a distorted view of it. Most of the people of colour who were in film school were there to give alternatives to exactly this kind of Hollywood films which gave a distorted view on who we are as people. This was also the case with Killer of Sheep: its objective was to change the perception of coloured people, in spite of what Hollywood had created, this myth, and to give voice to people who didn’t have access to Hollywood to tell their story. The film was made for multiple reasons: to demystify filmmaking in the community and to introduce filmmaking to kids, notably by having children work on the sound and on other technical aspects of the film. We wanted to show people who were interested in making a change in the community, to use film as a means for social change. This meant showing the community without imposing one’s own values on the film: making it appear to be a ‘documentary’, where I just set the camera and shot a story – while everything was written, of course. ‘To present a slice of life.’ If people were interested in making a change in the community, it wasn’t going to come from the notion that ‘if A, B, C and D would happen, then…’ I wanted to show a film where I’m questioning this very supposition: this is what you see and how do you intend to change it? How do you ‘help’ people in the community? That was the ‘reason’ at the basis of Killer of Sheep.”

Sabzian1

- 1Mattijs Driesen & Quinten Wyns, “Meeting Charles Burnett,” Sabzian, 14 June 2017.