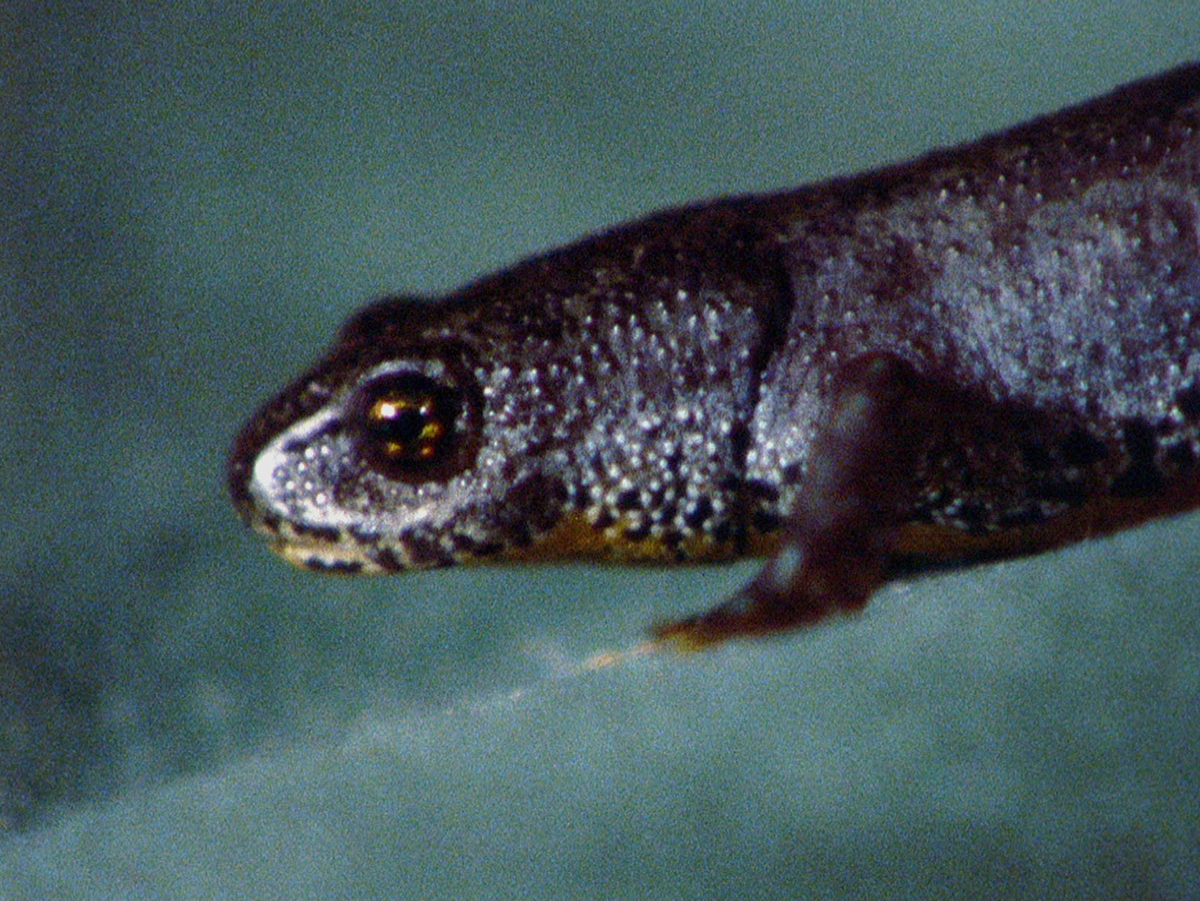

“London artist John Smith uses light-hearted humour to explore theoretical concerns – Gargantuan, for instance, is both pleasantly silly and acutely conscious of how imagery depends entirely on its framing. A voice-over intones the words ‘huge’ and ‘strapping’ as a lizard almost fills the screen, then ‘medium’ as the camera zooms out, then ‘tiny’, and finally ‘minute’, a pun on the film’s running time.”

Fred Camper1

“A wonderfully witty example of how to conduct pillow talk with a small amphibian.”

Elaine Paterson2

“To master the one minute time-span requires considerable discipline and few pieces if any had been shaped as genuine miniatures, most having the appearance of being extracts from larger works. The notable exception was John Smith’s Gargantuan which was not only the right length for the idea but actually incorporated a triple pun on the word ‘minute’.”

Nicky Hamlyn3

“To download Gargantuan and watch it on a good-sized computer monitor actually intensifies the ironies that Smith identifies. Enlarge the media player’s window until it is as big as possible, and play the movie. The first image of the newt, though larger in absolute terms than all earthly newts, will not be truly gargantuan, at least not in the Rabelaisian sense of that word. Considered in comparison with the scale in which it is presented in subsequent framings of the film, the newt is only relatively gargantuan. Indeed, this is part of the joke: not only is the scale of the newt determined by the rotation of the barrel of the zoom lens, but by the relative size of the screen or monitor on which it is shown. When I hook up my computer to a video projector, so that I may project Gargantuan on my classroom’s screen, the newt does approach Rabelaisian gargantuanness … but, then, not really: all that has occurred is a secondary level of magnification, in which the pixels that comprise the image are enlarged by the optics of the projector. The only absolute is the size of the newt relative to the size of the frame, a figure that may be expressed as a percentage, and that is subject to great variability.

The shifting of the scales of the newt, in fact, occurs largely in our minds. Ultimately, the argument that Smith makes in Gargantuan is that all viewers are burdened with a great many vital and fundamental – albeit unacknowledged – assumptions about the ways in which scale affects our perception of, understanding of, and responses to any and every filmed image. Remarkably, he makes this sophisticated point in a modest, clever, one-shot, (one-)minute film that consists of no more than a zoom-out of an amphibian. Thus does the message of Smith’s film echo its form: the minutest of things so often inspire the most gargantuan ideas.”

Ethan de Seife4

- 1Fred Camper, Chicago Reader, 2001.

- 2Elaine Paterson, Time Out, 1992.

- 3Nicky Hamlyn, “'One Minute TV 1992,” Vertigo, 1992.

- 4Ethan de Seife, “John Smith and His Gargantuan Newt,” Media Fields Journal.